Crossing chapters

Jump to:Video

The train explodes into the bus, leaving dead and injured children scattered on the cold ground.

Watch video

Watch video

Documents

Chapter 5 documents

- Report in Weld County District Attorney's file for the manslaughter case against school bus driver Duane Harms. The document does not indicate who wrote the report or what agency it came from.

- Transcript of interviews with children on the bus

- Front page of the Greeley Tribune on Dec. 14, 1961

- Accident report and map

Related content

Crossing forums

Forum at the Rocky Mountain News in Denver.

Forum at the Rocky Mountain News in Denver.

Forum at the Union Colony Civic Center in Greeley.

Forum at the Union Colony Civic Center in Greeley.

Podcasts:

Acknowledgements

"The Crossing" could only be told with the help of many people:

- The more than 80 people touched by the tragedy of Dec. 14, 1961, who agreed to tell their stories.

- Bill and Mary Bohlender, who helped unearth numerous historic documents and provided numerous insights.

- Virginia Shelton and Mary Shelton Shafer, who provided numerous insights and access to attorney Jim Shelton's files.

- Keith Blue, who provided numerous insights.

- Peggy Ford and the staff at the City of Greeley Museums, Barbara Dey and the Hart Library staff at the Colorado History Museum and former Rocky librarian Carol Kasel, who all assisted with research.

Contact the series team

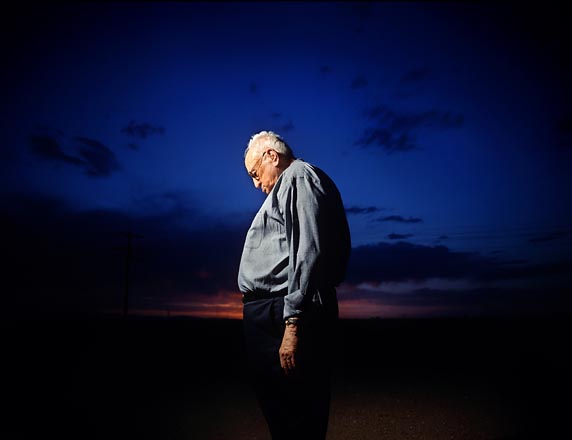

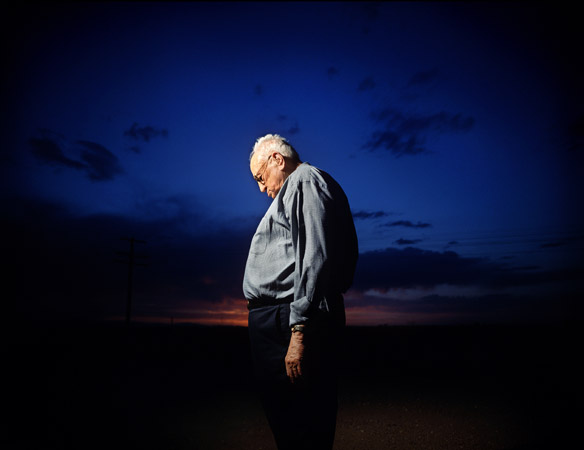

- Reporter: Kevin Vaughan

- Photographer: Chris Schneider

- Video: Tim Skillern & Laressa Bachelor

- Print designer: Armando Arrieta

- Web designer: Ken Harper

- Web producer: Forrest Stewart

- Web developer: Chris Nguyen

- Copy editor: Dianne Rose

- Photo editor: Dean Krakel

- Imager: Marie Griffin

- Interactive editor: Mike Noe

- Project editor: Carol Hanner

The Union Pacific passenger train barreled across the snow-dusted countryside at 79 mph, covering the length of a football field in less than three seconds.

The streamliner was just outside Greeley, 2 1/2 miles from LaSalle, its last planned stop before Denver's Union Station.

In the cab of locomotive No. 955 sat Herbert F. Sommers, a striped engineer's hat over his thinning hair and a pack of cigarettes in the front pocket of his overalls. Sommers looked out the window and saw a yellow school bus approaching the crossing ahead of him.

In the seat across the cab, fireman Melvin C. Swanson saw it, too.

"I hope he stops," Swanson said as the locomotive rushed toward the crossing. "There's children in that bus."

Sommers already had blasted the train's air horn. He rose up in his seat, reached for a cord over his head and gave the horn a few short toots, hoping to get the driver's attention. A moment later, the bus lurched onto the tracks.

Sommers grabbed the brass handle that activated his train's full emergency braking system. He knew even as he jerked the lever that it was too late. His 16-car train, pulled by three engines, would need a mile to stop, and he was no more than 75 feet from the crossing.

Disaster

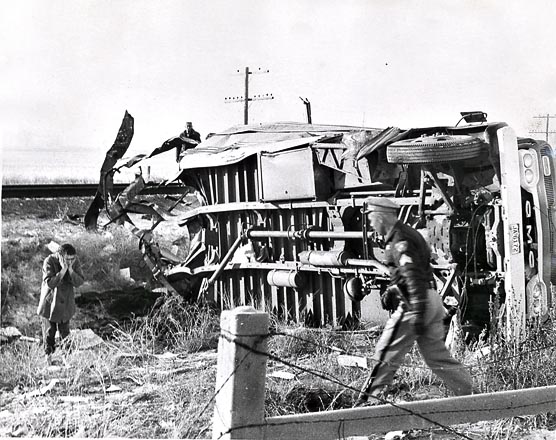

The violence of the next moment shattered the quiet morning. It was as if a bomb exploded between the rear wheels of the bus. The blunt nose of the locomotive tore into the last few feet of the school bus, shearing off the back end.

The impact hurled the front section of the bus into a barrel roll. The bus tore down the crossing sign as it tumbled to a stop on its side, landing 192 feet away. Its jumbled frame rails protruded next to a gaping hole where, an instant before, there had been children.

The locomotive carried the crumpled remains of the rear end of the bus 455 feet, dumping them upright on the other side of the tracks, four twisted seats left in the shattered hulk. The rear axle and dual wheels, ripped free, landed nearby.

Still more seats flew through the air and collapsed in a pile against a wire fence.

The crash scattered the children who had been in those seats. In less than four seconds, it was over.

School bus driver Duane Harms, blown out of the bus, awoke on the ground, got to his feet and stumbled around the scene, bleeding from cuts to his forehead and leg.

In those first confused moments, he wasn't sure what had happened.

Then he saw the train, idling down the tracks, and he knew.

Jerry Hembry, the front-seat passenger, had grabbed the pole next to him, bending it as he fought the overpowering force of the crash.

The impact had flung him out the huge hole in the back of the bus. He came to his senses as he rolled through a ditch next to the road.

Children lay around him. A boy next to him was dead.

Jerry stood up, cut and bruised, his shoulder dislocated, his collarbone broken.

He knew he had to get help. Despite his injuries, he picked up one little boy in his arms.

He took the hand of a girl and started walking west, toward a big white farmhouse a few hundred yards down the road.

"Jerry," one of the younger children said, "this didn't happen. It's a dream, isn't it?"

Alan Stromberger, who'd been sitting in the third row, found himself on the ground, cold, unable to walk.

Around him, it was as if someone had opened the rings on a school binder and allowed the wind to blow away the contents. School papers littered the ground. So did seats and glass and metal from the bus. And so did children — kids he knew — who moments before had been alive and happy and full of anticipation for Christmas.

Nancy Alles regained consciousness and heard kids around her moaning, groaning, crying. She did not know that her two cousins lay dead nearby.

Reaction

Albert Bindel, whose 68-acre farm sat next to the tracks just down the road from the crossing, pulled out of his driveway with three of his children, heading toward their Catholic school in Greeley.

A few seconds later, at the crossing, he stepped out of his '58 Ford, looked around, then jumped back in and gunned it for home.

He told the kids to go in the house, yelled to his wife, Irene, to call an ambulance and the state patrol, and took off.

Jim Ford was driving his wife, Loretta, to her house-cleaning job in Greeley when they came upon the scene. At first, Loretta thought a church bus had been hit by the train.

"No," Jim said, "it's not the church bus — it's our bus."

Their three boys had been on it. They found the oldest, 13-year-old Jimmy, dead along the tracks.

The youngest, Bruce, lay on the ground, knocked out. Their middle boy, Glen, climbed out of the wreckage. His face was battered, he couldn't see and he had a nasty cut on his leg, but he was alive.

Loretta and Jim Ford prayed over their dead son and the other children.

Trooper Don Girnt of the Colorado State Patrol was working U.S. 85 south of LaSalle when his radio crackled.

"Car 19," a dispatcher said, "you've got a school bus-train accident."

He floored it. By then, Bindel, the farmer who lived nearby, had raced his car into the yard of Joe and Katherine Brantner and their eight children.

Joe Brantner jumped in the Ford with Bindel, and they rushed the quarter mile to the crossing.

There, Joe Brantner found the bodies of two of his children, Mark, a kindergartner, and Kathy, a fourth-grader.

Somehow, Joe Brantner knew his grief would have to wait.

"Just take me back home and get my station wagon," he told Bindel.

The two men dashed back to the Brantner farm.

"Don't go up there," Joe told Katherine.

A minute later, the two men were back at the crossing, loading injured children into their cars. They picked up Nancy Alles, who had broken vertebrae and ribs. They carried Alice Larson, who was critically hurt with a torn liver and other injuries.

They grabbed Glen Ford, with cinders in his eyes, and Alan Stromberger, his back broken.

Girnt, the state trooper, whipped around a corner six minutes after hearing that first radio call. He stopped near the remains of the front section of the bus. He bolted from his white Plymouth. The first thing he saw was a child, dead on the road. Some of the injured children lay in shocked silence. Others cried for help.

A siren blared in the distance, grew closer. Then another, and another. Medics in ambulances slammed to a stop. Deputy sheriffs and state troopers skidded up to the crossing.

Phones rang.

A frantic message passed like a shock wave — a train hit the bus.

Parents, dozens in all, tore down the gravel roads to the crossing, to their worst fears. They ran up and down the tracks, where children, dead and alive, were strewn along a path of heartache more than 100 yards long.

Juanita Larson pulled up. She started to run, to look for her son, Steve, and daughter, Alice. A man with a badge stopped her.

Just then, Joe Brantner grabbed her.

His face was brave, his voice strong.

"Juanita, come with me," he said. "I have Alice, and she's badly hurt, and we have to get her to the hospital."

Juanita jumped in his station wagon.

Brantner and Bindel sped for town, their headlights burning, hands jammed hard on their horns. It would be hours before Juanita would find out what happened to Steve.

Outside the emergency room, Brantner, Bindel and Juanita Larson got the injured kids out of the cars.

They put Alice on a gurney. Joe Brantner grabbed Juanita again, gave her a hug. Then he put his head against the wall.

"Both of mine are gone, Juanita," he said, heartbreak in his voice. "Go take care of Alice."

Tragic toll

Girnt and other investigators began calculating the toll of the deadliest traffic accident in Colorado history. In all, 20 children were dead:

Cindy Dorn, 11, and her cousin, Linda Alles, 10, carrying her brother's wrestling medal for show-and-tell.

Calvin Craven, celebrating his 10th birthday; his sister, Ellen, 8; and their cousin, Jerry Baxter, 10.

Kathy Brantner, 9, and Mark Brantner, 6, whose father found them dead, then went to work helping others.

Jimmy Ford, 13, the cowboy with the square jaw.

April Freeman, 8, the girl everyone called by her middle name, Melody.

Kathy Heimbuck, 12, and her sister Pam, 9, who loved her pony, Dopey.

Steve Larson, 9, the fast-growing Cub Scout.

Mary Lozano, 10, who scurried to find her purse before getting on the bus.

Sherry Mitchell, 6, who wanted to see her dad in the hospital instead of getting on the bus.

Marilyn Paxton, 13, and Jan Paxton, 11 — the sisters who loved to dance.

Bobby Smock, 10, a little cowboy with his own chaps.

Linda Walso, 13, whose mother led the "Auburnettes" 4-H group.

Elaine White, 11, and her sister, Juleen, 8.

Sixteen other children, some near death, some battered and bruised, were still alive:

Nancy Alles, 11, whose brother had gone to the dentist instead of riding the bus.

Cheryl Brown, 13, who had a Confederate $5 bill in her wallet.

Bruce Ford, 9, and his brother Glen, 11.

Joy Freeman, 10, and her brother Smith, 7.

Randy Geisick, 8, who lost his holiday wrapping paper — and one shoe — in the crash.

Jerry Hembry, 16, the oldest student on the bus.

Alice Larson, 11, who had swapped seats with her little brother.

Luis Lozano, 9, who had leaned over the seat to watch two girls color in a book.

The three Munson children — Vicky, 6; Gary, 8; and Johnny, 9 — whose father had dropped them at the bus early so they didn't have to wait in the cold.

Alan Stromberger, 10, and his sister Debbie, 7.

Jacquelyn White, 14.

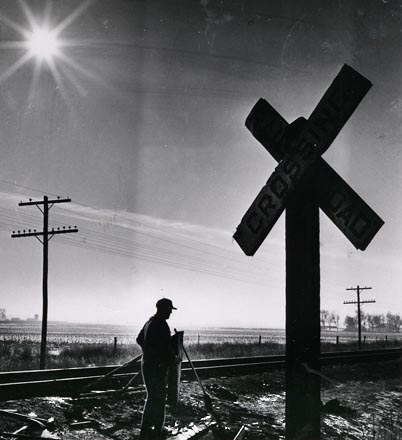

In the coming weeks, Trooper Girnt, the first officer at the scene, would spend hours measuring the crossing, diagramming its sharp angle.

He would spend mornings at the side of the road, a stopwatch in his hand, waiting for the train, determining when its headlight came into view.

He would eventually calculate that the line between life and death was 63 inches wide.

The bus had almost made it across the tracks.

NEXT: All out