Crossing chapters

Jump to:Documents

Chapter 9 documents

Related content

Crossing forums

Forum at the Rocky Mountain News in Denver.

Forum at the Rocky Mountain News in Denver.

Forum at the Union Colony Civic Center in Greeley.

Forum at the Union Colony Civic Center in Greeley.

Podcasts:

Acknowledgements

"The Crossing" could only be told with the help of many people:

- The more than 80 people touched by the tragedy of Dec. 14, 1961, who agreed to tell their stories.

- Bill and Mary Bohlender, who helped unearth numerous historic documents and provided numerous insights.

- Virginia Shelton and Mary Shelton Shafer, who provided numerous insights and access to attorney Jim Shelton's files.

- Keith Blue, who provided numerous insights.

- Peggy Ford and the staff at the City of Greeley Museums, Barbara Dey and the Hart Library staff at the Colorado History Museum and former Rocky librarian Carol Kasel, who all assisted with research.

Contact the series team

- Reporter: Kevin Vaughan

- Photographer: Chris Schneider

- Video: Tim Skillern & Laressa Bachelor

- Print designer: Armando Arrieta

- Web designer: Ken Harper

- Web producer: Forrest Stewart

- Web developer: Chris Nguyen

- Copy editor: Dianne Rose

- Photo editor: Dean Krakel

- Imager: Marie Griffin

- Interactive editor: Mike Noe

- Project editor: Carol Hanner

In the weeks after school bus driver Duane Harms was charged with manslaughter, nearly four dozen letters landed on the desk of prosecutor Karl Ahlborn in Greeley.

Some handwritten, some typed on onion-skin paper, they all came from people touched deeply by the tragedy of Dec. 14, 1961. A few urged harsh action against Harms.

I think the driver of the bus should be made an example for needless manslaughter. I don't see how he can live with himself knowing he was to blame as a reckless piece of humanity.

Unsigned, from Spokane, Wash.

Several blasted the Union Pacific railroad.

I wonder why it is that the railroads are always right when they kill people at railroad crossings and the drivers in automobiles and trucks are always to blame.

An observer and resident of Colorado

Many more — 30 in all — expressed support and compassion for Harms.

For two years I had the privilege of hiring Duane and I can tell you very honestly he was one of the few boys I have hired that I allowed to drive my pickup and car ... In my opinion this fine young man deserves better treatment than he has had. I am sure you will be kind as well as just.

Norris Pyle, Fleming

My son will testify for him if needed for there doesn't have to be a court of law to punish him — he has to live with this his self. That's enough.

Dorris Collins Briles, Greeley

I only felt the urge to write this letter to you, so you may convey the wishes and the devoted prayers of a Methodist minister down in Texas, and pray all charges, ill will, and injustice shall be withdrawn from this young man, Mr. Duane Harms.

Travis L. Darby, Port Arthur, Texas

But the letters did not deter prosecutor Ahlborn. Neither did the parents who urged him to let Harms go free, even though their children had been on the bus.

And so the manslaughter trial of Duane R. Harms, case No. 5815, began quietly on March 20, 1962, at the stately Weld County courthouse in downtown Greeley.

That Tuesday morning, 130 potential jurors climbed the 67 marble steps to the fourth floor and Judge Donald Carpenter's courtroom. Barely three months had passed since the deadliest traffic accident in Colorado history. Six miles separated the courthouse from the crossing where it happened.

Hours of questions, challenges and decisions ended with 10 men and two women chosen to decide whether Harms committed a crime at the crossing.

They would have to answer, in essence, one question: Did Harms stop and look on Dec. 14, 1961, in the moments before a high-speed passenger train tore through his school bus?

The jurors selected as their foreman Alan "Bud" Middaugh, a 32-year-old cattle buyer for the Monfort family. He wanted the job, and the others were relieved when he agreed to do it.

It had been a long day for everyone, an even longer one for Harms, 23 years old with a daughter born just months earlier. Before it ended, Weld County Sheriff Bob Welsh handed Harms two summonses. He had been named a defendant — along with the school district, Union Pacific and train engineer Herbert F. Sommers — in a $75,000 lawsuit filed by the families of three children who had died.

At 9:30 the next morning, everyone was back in court.

Prosecutor Ahlborn went first.

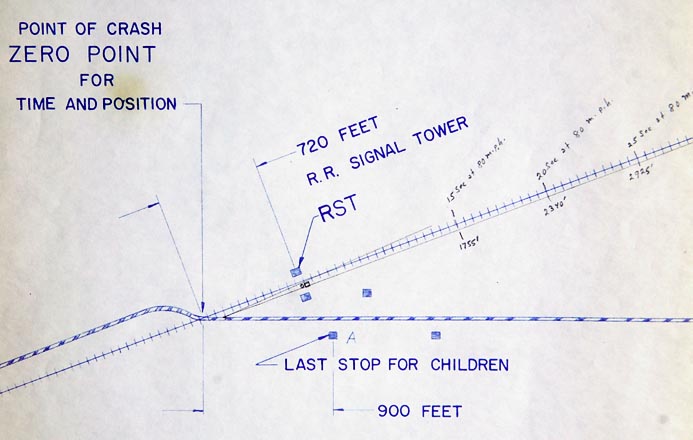

Harms, he said, was guilty because he didn't take the time to be careful. Because he didn't bother to look at a railroad signal light 728 feet east of the crossing, which clicked on 30 seconds before the train's headlight came into view.

Because he didn't bother to look for that burning headlight, visible for 2 1/2 minutes before the train could be seen.

And because he didn't bother to look for the train, which was visible for 44 seconds before it ripped his school bus in two.

Jim Shelton, Harms' court-appointed attorney, stood. He was determined to stop his young client's life from being ruined by a mistake he believed anyone could have made. Harms, he said, followed all the rules in his manual.

"He was totally unaware a train was approaching," Shelton said. "Duane Harms had no consciousness that his acts would harm the passengers on his bus. If he did anything wrong, it did not constitute criminal negligence."

'Poor little children'

Parents — some who had lost children, some who hadn't — sat quietly in the back of the courtroom as a series of prosecution witnesses took their turns on the stand.

A Union Pacific supervisor described the speed tape locked in the locomotive cab that showed the train had approached the crossing at 79 mph, the limit on that stretch of tracks.

Sommers, the 64-year-old engineer, said Harms had slowed, but not stopped, at the crossing.

"The windows were frosted up, but not so much you couldn't see those poor little children down there," he said. "You couldn't recognize them ... just sort of see images."

State Trooper Don Girnt walked jurors through the scene, recounting his measurements and calculations.

Thursday came, and Girnt returned to the stand, followed by four other detectives. All said that in their initial questioning of

Harms, he seemed unsure whether he had stopped at the crossing.

Ahlborn rested his case. He and Deputy District Attorney Bill Bohlender had called 13 witnesses.

Shelton opened the defense with Albert Bindel. The farmer told the jurors how he'd been outside when the bus passed, how he'd heard the train approaching and looked west toward the crossing.

"As near as I could tell, the bus was stopped at the crossing," he testified. "The red lights, about halfway down on the bus, were on.

"I came to the conclusion he was stopped, and I went into the house to take my children to school."

A parent speaks

Then Art Larson, a slender 6-footer, stepped to the witness stand and raised his right hand, ready to swear to God to tell the truth.

A truck driver and farmer of Swedish descent, Arthur Gustav Larson may have seemed an unlikely defense witness, for he had experienced the full range of emotions since Dec. 14, 1961.

Thankfulness, that his daughter, Linda, had stayed home with a cold and missed the bus.

Relief, that his daughter, Alice, was recovering from a crushed gallbladder and torn liver and appendix.

Heartbreak, that his son, Steve, had died.

Other parents had abandoned Harms. They'd threatened him, pushed for jail time.

But Larson had not. He had not forgotten how careful Harms had always been, how much he had helped soothe Steve as the awkward boy struggled to fit in among the other kids. He had not forgotten the courage Harms had shown four days after the accident, visiting Alice in the hospital. She awakened from her coma while Harms was in her room.

Larson had been in a unique position, just moments before the train hit the bus, to answer the question that could determine Harms' fate.

He told the jurors about sending Alice and Steve to catch the bus, about getting into his delivery truck to take his oldest daughter, Nancy, into Greeley, where she attended College High.

He told them how he'd pulled up to the railroad tracks just as the streamliner flashed by him. He told them how he had looked to the west to see the bus stopped at the next crossing, a little more than half a mile away.

"I had no doubt," he testified. "I was sure the bus stopped, and that he'd seen the train, so I went on to town."

Jerry Hembry, a 16-year-old whose wrestling season ended when the collision tore apart his shoulder, was just as firm.

"The bus stopped," he testified. "I didn't hear the train whistle or see anything."

On Friday morning — Day Four — Harms put on a coat and tie again and headed to the courthouse. The jurors — and the families of many of the dead children — would hear his version of events.

"I usually stop, open the door, listen, then turn around and raise up so I can see over the kids," he testified. "Then I look in the mirror."

It was, he told the jurors, "a normal morning." Under questioning from Shelton, he said he specifically remembered that he opened the door, turned in his seat and tried to look down the tracks. He said his vision was obscured by frost on the bus windows. He said he did not remember the actual crash.

"When I remember, I recall lying down in front of the bus," he said quietly. "It looked like it had been cut off or blown off, I didn't know which.

"I walked back around the bus and saw the train down the track. Then I knew what had happened."

And so it went for hours. Harms did not break down. He did not back down, either, insisting that he must have stopped at the crossing.

Friday afternoon came, but the trial ground on. Rebuttal witnesses testified. Shelton and Ahlborn took turns with closing arguments. Judge Carpenter read 19 pages of instructions to the 10 men and two women of the jury.

Finally, at 9:58 p.m., the case was theirs.

NEXT: Verdict