Crossing chapters

Jump to:Video

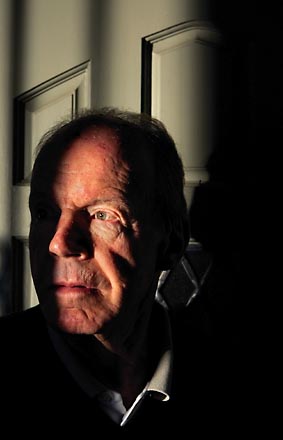

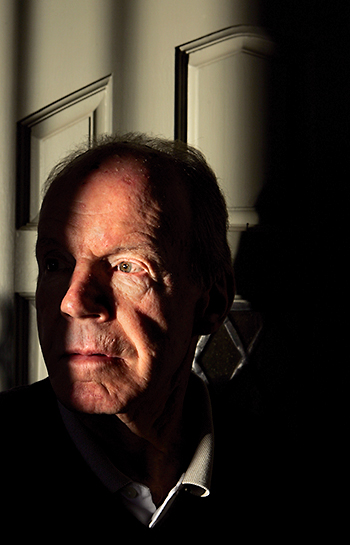

Duane Harms went free after his acquittal on manslaughter charges, but he couldn't escape his fear of retribution.

Watch video

Watch video

Documents

Chapter 10 documents

- Letter from school bus driver Duane Harms and his wife, Judy, to his lawyer, James H. Shelton, after Harms' acquittal on manslaughter charges

- Interstate Commerce Commission report on the accident

- Record of Duane Harms' acquittal

- Letter from bus driver Duane Harms and his wife, Judy, to Colorado Sen. John Carroll, his reply letter and the Congressional Record with his statement and newspaper editorials on the crash

Related content

Crossing forums

Forum at the Rocky Mountain News in Denver.

Forum at the Rocky Mountain News in Denver.

Forum at the Union Colony Civic Center in Greeley.

Forum at the Union Colony Civic Center in Greeley.

Podcasts:

Acknowledgements

"The Crossing" could only be told with the help of many people:

- The more than 80 people touched by the tragedy of Dec. 14, 1961, who agreed to tell their stories.

- Bill and Mary Bohlender, who helped unearth numerous historic documents and provided numerous insights.

- Virginia Shelton and Mary Shelton Shafer, who provided numerous insights and access to attorney Jim Shelton's files.

- Keith Blue, who provided numerous insights.

- Peggy Ford and the staff at the City of Greeley Museums, Barbara Dey and the Hart Library staff at the Colorado History Museum and former Rocky librarian Carol Kasel, who all assisted with research.

Contact the series team

- Reporter: Kevin Vaughan

- Photographer: Chris Schneider

- Video: Tim Skillern & Laressa Bachelor

- Print designer: Armando Arrieta

- Web designer: Ken Harper

- Web producer: Forrest Stewart

- Web developer: Chris Nguyen

- Copy editor: Dianne Rose

- Photo editor: Dean Krakel

- Imager: Marie Griffin

- Interactive editor: Mike Noe

- Project editor: Carol Hanner

Through the long night of deliberations, the jury had talked and voted and gotten discouraged and talked some more and voted again.

Some feared it was futile, that they'd never all agree on whether school bus driver Duane Harms committed manslaughter when a train sliced his bus in two and killed 20 children.

At midnight, after two hours in the jury room, they told the judge they would keep going until they reached a verdict.

As dawn arrived on Saturday, March 24, 1962, foreman Alan "Bud" Middaugh called for another vote. It was the fourth one, and it was unanimous.

Now it was time to read it.

Harms, the shy, quiet bus driver and janitor, sat at the defense table after a grueling four days on trial.

He'd relived the worst day of his life on the witness stand, been sued for hundreds of thousands of dollars and spent an anxious night in the courthouse, his parents at his side.

His attorney, Jim Shelton, sat next to him. Prosecutor Karl Ahlborn and his assistant, Bill Bohlender, waited, too.

Judge Donald Carpenter called for the verdict.

"Not guilty."

Harms showed little emotion.

After Carpenter thanked the jurors for their service, Harms walked out into a swarm of reporters. He was too tired to talk, he said simply, and headed home.

But the acquittal didn't bring peace.

Within a few hours, Weld County Sheriff Bob Welsh showed up at Harms' modest home to serve him with papers. More lawsuits.

A few days later, Judy Harms sat down and wrote a letter to Shelton, her husband's court-appointed attorney.

This is just a note to let you know how much we have appreciated all your hard work and friendship. Even though the verdict may have been the opposite our feeling would still be that you did everything that could be done. We congratulate you with all sincerity and want you to accept our gratefulness.

She signed it for both of them.

Judy and Duane Harms

The troubles still piled up. More summonses for more lawsuits arrived.

The Interstate Commerce Commission issued a blistering ruling, pointing out that both men in the train cab were positive Harms had not stopped, looked or listened for the locomotive.

The ruling noted that Harms had not been sure he stopped before crossing the tracks.

"Under these circumstances, it is apparent that had the driver of the school bus taken adequate precautions before driving onto the crossing he would have seen the train approaching and heard the sound of the locomotive horn, and thereby be warned that it was unsafe to proceed over the track and the accident would have been averted."

Crank phone calls, threats and angry parents tormented Harms.

I want you to know that you killed my kids, Jim Paxton, who lost both his daughters, told Harms in one confrontation.

I made a mistake that day, Harms replied.

You bet you did, Paxton said. You killed my kids.

The feeling wasn't unanimous. Many people — even many couples who had lost children — supported Harms.

But it didn't matter.

Harms lived in constant fear.

By summer, he was gone, never to live in Colorado again.

He still had the lawsuits to face — they would eventually be settled out of court — but he packed up Judy and their baby daughter, Lynda, and headed west, to what he hoped would be a new life away from the anguish of Dec. 14, 1961.

Hard to forgive

Forty-five years later, the anger remains for at least two families.

Ed and Betty Heimbuck, who lost their only two children — Kathy, 12, and Pam, 9 — blame one person and one person only: Duane Harms.

They know it wasn't intentional. They know he came from a good family. And yet, it bothers them still that the jury found him not guilty of manslaughter.

"It doesn't change anything," says Betty Heimbuck, who lives in LaSalle. "I never wanted him to go to prison. I just wanted them to say it was his fault. But they didn't.

"But he was the driver. He drove them up onto the tracks."

Her thoughts are echoed by Alice Paxton, who lives in Pierce, north of Greeley.

Her husband, Jim, who had confronted Harms in the days after the accident, remained bitter over the loss of their daughters, Marilyn, 13, and Jan, 11, until the day he died in late 2005.

"We were really disappointed," Alice says of the verdict.

But they were the minority after the accident, and they are the minority today.

"He would never ever hurt one of those kids on that bus," says Kathy Allmer, whose 10-year-old brother, Bobby Smock, died in the crash.

"He had an awesome rapport with those kids. An awesome rapport."

She says her parents, who are no longer living, never blamed Harms.

"I think if we all felt that he was reckless, that would be a different thing," she says from her home in Dewey, Ariz. "But we knew that he wasn't. He insisted that the kids sit down, and they didn't roughhouse in the bus, and if you wanted to play games in the bus you got asked not to ride the bus, plain and simple."

In Battle Ground, Wash., Jerry Hembry expresses similar feelings.

At 16, he was the oldest passenger on the bus and sat in the front seat, looking down the tracks when Harms did.

He never saw the train until it was on top of them.

And though he was seriously injured, he testified for Harms, telling jurors that Harms had stopped, opened the door, looked and listened.

"He's a very dear man — a very good man," Jerry says today. "Everybody greeted him every morning on the bus. He was just very — you couldn't ask for a more wonderful person. Caring. Why God would choose a man like him to put him through such torture ..."

'Very kind man'

Alan Stromberger, who suffered a broken back and whose sister fought for her life for days after the wreck, now lives about 10 miles from where Harms grew up in Fleming.

"I really don't blame him," Alan says.

"I feel it was an accident. My thoughts of him was that he was a very quiet and very kind man. Maybe I'd have different feelings if we'd have been injured worse or had lost a family member."

Loretta Ford, who put three sons on the bus that morning and buried her oldest, remembers the night a few weeks after the accident when some men came to her house with a petition, seeking jail for Harms.

She refused to sign it.

"We liked him," she says on the porch of her home northeast of Kersey.

"He warmed that bus up for the kids. He was kind of a friend to them at school."

Many of those touched by the tragedy believe that what happened at the crossing was out of Harms' control.

"It's fate," says Cheryl Brown Hiatt, a Fort Collins woman who suffered a broken back and other injuries in the crash. "As far as I'm concerned, God's the one that decided that. That's been my belief all along. God's the one that puts you on this earth, and God's the one that takes you away."

Art and Juanita Larson, despite the loss of their son and the injuries to their daughter, will never forget the way Harms helped Steve, and the visit he made to Alice in the hospital.

"We just have so much to be grateful for," Juanita says. "How can you harbor a grudge over an accident?"

For years, nobody really knew what became of Harms. From time to time, a new rumor made its way around the Greeley area.

Someone said he'd changed his name. Someone said he was in a mental institution.

And many touched by the crash heard the same story: He'd killed himself.

NEXT: Reverberations