Crossing chapters

Jump to:Related content

Crossing forums

Forum at the Rocky Mountain News in Denver.

Forum at the Rocky Mountain News in Denver.

Forum at the Union Colony Civic Center in Greeley.

Forum at the Union Colony Civic Center in Greeley.

Podcasts:

Acknowledgements

"The Crossing" could only be told with the help of many people:

- The more than 80 people touched by the tragedy of Dec. 14, 1961, who agreed to tell their stories.

- Bill and Mary Bohlender, who helped unearth numerous historic documents and provided numerous insights.

- Virginia Shelton and Mary Shelton Shafer, who provided numerous insights and access to attorney Jim Shelton's files.

- Keith Blue, who provided numerous insights.

- Peggy Ford and the staff at the City of Greeley Museums, Barbara Dey and the Hart Library staff at the Colorado History Museum and former Rocky librarian Carol Kasel, who all assisted with research.

Contact the series team

- Reporter: Kevin Vaughan

- Photographer: Chris Schneider

- Video: Tim Skillern & Laressa Bachelor

- Print designer: Armando Arrieta

- Web designer: Ken Harper

- Web producer: Forrest Stewart

- Web developer: Chris Nguyen

- Copy editor: Dianne Rose

- Photo editor: Dean Krakel

- Imager: Marie Griffin

- Interactive editor: Mike Noe

- Project editor: Carol Hanner

As he faced the railroad tracks at 7:59 a.m. on Dec. 14, 1961, doing a job he never wanted, school bus driver Duane Harms was perched at a precipice.

Life as it had always been in the Auburn farming community hung there with him, its final seconds quickly slipping away.

A 23-year-old with a newborn daughter, Harms had been content as a janitor at Delta Elementary outside Greeley. The work kept him busy, and it was only temporary, anyway, while his wife finished college and earned her teaching certificate. But his boss wanted him to drive the bus, and after days of wrangling he'd finally agreed to add that to his cleaning duties.

The people of Auburn had been content, too, with their three-room country school, where generations of kids had learned to read and write and add and subtract. Many could walk to the blond-brick schoolhouse. Some rode their horses, tying them up out back between the old outhouses.

But those times were gone. The Auburn school was shuttered. Now, the boys and girls stamped their feet and fidgeted against the brutally cold morning, farm kids on the edge of the road, waiting to board the bus.

Girls wore print dresses and bundled up in wool coats and hand-knitted mittens and caps. Boys pulled rubber galoshes over their shoes.

They carried their books — Learning To Use Arithmetic and Roads to Everywhere — under their arms with their three-ring binders.

They clutched sack lunches.

They were living on the cusp of tremendous change — in the country, in Colorado, in Auburn. John F. Kennedy — the youngest American president and the first born in the 20th century — was celebrating his first Christmas season in the White House. Just the night before, he and first lady Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy attended a party for White House employees in the East Room.

In Colorado, a wave of school district consolidations had swept the state.

Less than two generations before, the state had more than 2,000 districts, many with only one building.

By the mid-1950s, a legislative study had declared reorganization of Colorado's school districts the state's top educational priority. Between 1956 and 1961, nearly 700 had been eliminated. Only 275 remained.

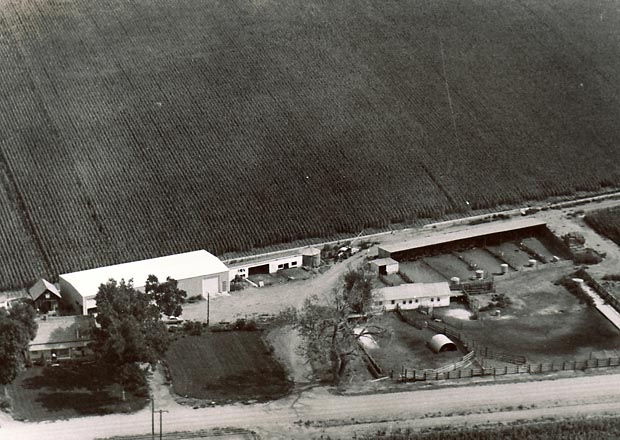

One victim was the Auburn district, about five miles southeast of Greeley.

Little money but not poor

The farm families of Auburn scratched out a life in the flat fields, sometimes working 20 hours a day, fixing whatever broke, sewing their own clothes, making do with what they had. Many rented their homes and land, and some farm workers lived in houses provided by their employers.

They grew their own vegetables, butchered their own chickens.

Most of them — children and grandchildren of German-Russian and Swedish immigrants who came to America with nothing — considered themselves fortunate.

Art and Juanita Larson certainly did.

She put in 28 or 29 days a month as a nurse's aide at Weld County General Hospital in Greeley. He drove a delivery truck six days a week. Their monthly income — $200 — allowed them to buy their 23-acre farm in Auburn in 1957.

They lived in a three-room home cobbled together from two old shacks that once housed farm laborers. Their four kids slept in one room in bunk beds. Art and Juanita slept in a bed in the living room. In their kitchen sat a luxury that would have been unthinkable only a few years before — an electric range. Juanita hadn't forgotten her childhood, scavenging in the fields for dry cow chips to burn in a wood stove.

Now Juanita drove home after her overnight shift at the hospital, stood in front of her electric range and cooked breakfast.

Saturdays and Sundays meant bacon and eggs, toast, warmed-up potatoes or hash browns. On school days like this one, she fixed oatmeal or Cream of Wheat.

A kerosene heater fought an ongoing battle against the cold that leaked through the old, creaky windows in the drafty house. The neighbor kids got their first driving lessons in the family's 1940 International pickup. With the truck's low "granny gear," the kids couldn't stall the engine, and they couldn't go more than 2 or 3 mph.

The Larson farm sat a half mile from the Union Pacific tracks, which cut diagonally through Auburn in a straight, six-mile line into LaSalle.

Near the end of an era

Twice a day the City of Denver streamliner pounded down those rails, close enough that the people of Auburn could see her hurry past. Each morning, she thumped by, heading west, an hour away from the end of her Chicago-to-Denver run. Each afternoon, she hammered by on her way to the Windy City.

The train had been christened amid fanfare and champagne on June 18, 1936, as a joint venture of two railroad lines. That afternoon, Fredrika Sargent, whose father was president of the Chicago and Northwestern Railway Co., took two whacks with a bottle of champagne over the nose of an engine in Chicago, inaugurating the line. Less than a minute later, at Denver's Union Station, Janet Grace Johnson, daughter of Colorado Gov. "Big Ed" Johnson, busted a bottle of champagne over the prow of a sister locomotive.

Then they were off — the twin maiden voyages of the City of Denver.

The 12-car train in Chicago covered the 1,048 miles to Denver in 16 hours — an average of 65.5 miles per hour, including stops.

She was the fastest long-distance passenger train in the world. And in the days before air travel was safe, easy and inexpensive, before the interstate highway system snaked around the country, she shuttled her passengers across the land in luxury.

As close as she was to the people of Auburn — close enough that they could feel the power in her diesel locomotives — she was out reach for most of them. A one-way, first-class ticket was $39.95, plus taxes. Her passengers ate seven-course meals on Union Pacific china. Sipped coffee in comfort as the train thrummed along at 80 mph. Wiped their mouths with linen napkins.

They gazed out of the glass-domed coaches as the landscape streamed past. Slept comfortably in Pullman cars. Rarely heard the rumble of the locomotives or the full-throated wail of her air horns at crossings.

But on this day, as the City of Denver dashed through the farm fields of Auburn, the train was doomed. It would be a decade before her obituary was finally written, but the Boeing 707 was already in the air, and it could make the Chicago-to-Denver hop in less than three hours.

Herbert F. Sommers, the 64-year-old engineer at the throttle of the City of Denver, was a creature of that dying era. For more than 40 years, the railroad was all he had ever known. Two months before Pearl Harbor, he'd been promoted to engineer.

For years, he'd lived the nomadic life of a railroad man, shuttling freight trains up and down the rails at all hours of the day and night. Then, as the autumn of 1961 arrived, he snagged a coveted slot on the City of Denver.

About three months later, at 7:59 a.m. on Dec. 14, 1961, his locomotive, its horn blasting, roared for the angled crossing 2 1/2 miles from LaSalle, where Duane Harms had to twist around in his seat to see if a train was coming.

At the crossing, Harms thought everything was clear for him and the 36 children aboard his school bus. He wrapped his right hand around the big polished lever in the middle of the dashboard, shoving the door closed.

As Harms let out the clutch, the bus trembled and started for the tracks.

Jerry Hembry, a 16-year-old in the front seat next to the door, raised his arm and wiped the frost from the window next to him.

He glanced down the tracks, saw nothing coming, then turned and looked forward. As the front wheels of the bus bumped across the rails, he turned to his right again.

In that instant, he saw the bright yellow headlight and the bright yellow nose of the City of Denver's lead engine bearing down on them.

He instinctively grabbed for the shiny steel pole to his left and shouted: "Train!"

NEXT: 63 inches