Crossing chapters

Jump to:Related content

Crossing forums

Forum at the Rocky Mountain News in Denver.

Forum at the Rocky Mountain News in Denver.

Forum at the Union Colony Civic Center in Greeley.

Forum at the Union Colony Civic Center in Greeley.

Podcasts:

Acknowledgements

"The Crossing" could only be told with the help of many people:

- The more than 80 people touched by the tragedy of Dec. 14, 1961, who agreed to tell their stories.

- Bill and Mary Bohlender, who helped unearth numerous historic documents and provided numerous insights.

- Virginia Shelton and Mary Shelton Shafer, who provided numerous insights and access to attorney Jim Shelton's files.

- Keith Blue, who provided numerous insights.

- Peggy Ford and the staff at the City of Greeley Museums, Barbara Dey and the Hart Library staff at the Colorado History Museum and former Rocky librarian Carol Kasel, who all assisted with research.

Contact the series team

- Reporter: Kevin Vaughan

- Photographer: Chris Schneider

- Video: Tim Skillern & Laressa Bachelor

- Print designer: Armando Arrieta

- Web designer: Ken Harper

- Web producer: Forrest Stewart

- Web developer: Chris Nguyen

- Copy editor: Dianne Rose

- Photo editor: Dean Krakel

- Imager: Marie Griffin

- Interactive editor: Mike Noe

- Project editor: Carol Hanner

Whether it was a basketball game in a loud gymnasium or a football game on a cold fall evening, when Roy Werner suited up for his Pawnee Jackrabbits, two people always sat in the stands to cheer him on.

Dick and Dorothy Smock were his grandparents.

"It didn't matter where I was playing, they were there," Roy says today from his home in Pine Bluffs, Wyo., more than two decades removed from his high school graduation. He has never forgotten their devotion during a confusing time in his life.

He gave the Smocks something in return. He opened a window to a part of their life they thought had closed on Dec. 14, 1961.

That was the day Bobby, their only son, died in the crash at the crossing.

Roy offered them a chance to experience high school games and hunting trips and things they never got to do with the son they lost.

Never the same

Dick Smock was a short man, not much over 5 feet tall, but he stood a lot taller in his cowboy hat. He worked in Greeley, first at an oil company, later for the county's road department, and he always had a small farm and some cattle and horses.

He was tough, and he could be ornery.

Dorothy Smock wasn't any taller. She was a round woman with dark hair and brown eyes.

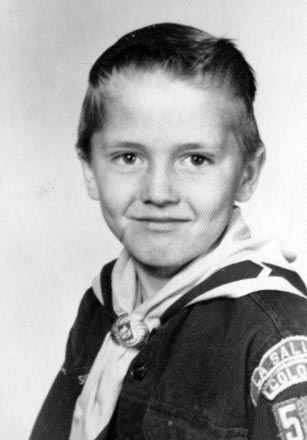

In December 1961, their daughters Judy and Kathy were 17 and 15, and Bobby was 10.

Bobby was all cowboy, wearing chaps and spurs and a toy gun when he rode his horse, playing around with his cocker spaniel, Spotty.

On Dec. 13, Kathy came home from the hospital after having her tonsils removed.

That night, Dick Smock made plans to go to a livestock sale the next day — Thursday, Dec. 14. Bobby wanted to go with him.

"No," Dick told his son, "you have to go to school."

Kathy was home, nursing her sore throat, when the phone rang. A train had slammed into the school bus.

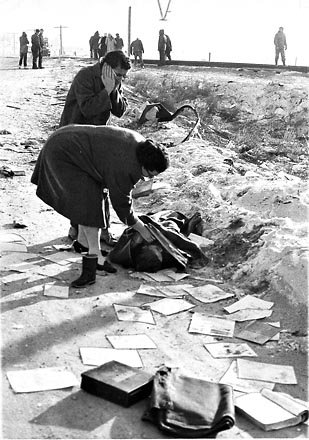

Dorothy and a neighbor, Aleta Craven, sped to the scene. Ellen Craven, 8; her brother Calvin, who turned 10 years old that day; and their cousin, Jerry Baxter, 10, were all on the bus with Bobby.

All four children died in the crash.

Near the crushed front section of the bus, Dorothy and Jerry's mom, Marie "Ruby" Baxter, came upon a blanket covering a lifeless form on the frozen ground. Dorothy lifted the blanket.

It was Bobby.

A news photographer snapped a picture, capturing that moment of utter heartbreak.

Later, someone laid Bobby in Dorothy's arms, and she held him for a long time before finally letting him go.

At home, Bobby's sister, Kathy, didn't know yet the extent of the tragedy.

"They were gone, it seemed like forever, and when they came back, they didn't have any of the kids," Kathy Smock Allmer says from her home in Dewey, Ariz.

"It's something I never want to live through again."

The vision of her dead boy resting in her lap haunted Dorothy for the rest of her life.

Dick was haunted, too: If only I'd taken Bobby to the sale with me.

"I can't say they weren't good parents," Kathy says, "but the hole was there."

Kathy's sister, Judy Smock LaMaster, remembers it, too.

"Every little thing would bother Momma," she says. "That empty spot was there."

"And Daddy, he just never really talked about it."

Then, when they were at an age long past the time most people have children at home, the Smocks took in Roy, Judy's son.

He had spent summers with them since he was small. At age 15, his parents, Judy and Kent Werner, divorced, and both moved. Roy didn't want to live with either of them, so he moved onto his grandparents' ranch west of Grover.

Another chance

Roy forged a relationship with them that was much more than grandparent-grandchild.

"He was kinda like my dad for a long time," Roy says.

And Dorothy was like a mother. The two of them were always there to root Roy on.

They pulled for him at football games, where he suited up at running back and defensive lineman on his six-man team. At basketball games, where he played guard. At baseball games, where he manned right field.

In the summer, while Dick drove a road grader for the county, Roy tended to the animals and did chores around the farm, as a son would do.

If they were out working, and it was 11 o'clock, they dropped what they were doing for a one-hour break to watch All-Star Wrestling.

Roy hunted with his grandfather, rode horses with him, ate vanilla ice cream with him.

"We did a lot of stuff together as a family — Grandpa and Grandma and I did," Roy says.

They went together to rodeos to watch the Ford boys, Bruce and Glen. Bruce had been friends with young Bobby Smock.

In his early 20s, Roy moved out. His grandparents have been gone for years now, but Roy often thinks of them, about their gift to him at a time he needed it.

"They were good people," he says. "They had hearts of gold, and they'd do anything for any of their kids and anybody else."

But the thing is, Roy gave his grandparents a tremendous gift, too.

"It kind of filled the hole up," Roy's mother, Judy LaMaster, says from her home in Kimball, Neb.

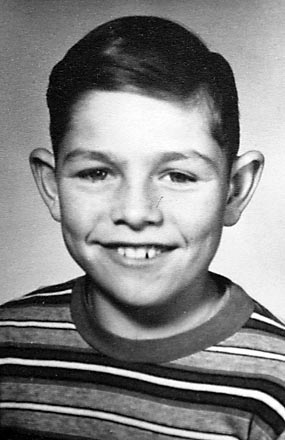

Judy and Kathy? They have their own void — the empty spot left by not knowing how their brother might have grown up.

"You kind of wonder, you know, how would he look now?" Kathy asks. "Would he be married? Would he have children? What kind of life would he have had?"

As with so many other things about Dec. 14, 1961, there is no way to know.

NEXT: The judge

This story corrects the team name for Pawnee high school. The team name was changed from Jackrabbits to Coyotes after 1985.