Crossing chapters

Jump to:Related content

Crossing forums

Forum at the Rocky Mountain News in Denver.

Forum at the Rocky Mountain News in Denver.

Forum at the Union Colony Civic Center in Greeley.

Forum at the Union Colony Civic Center in Greeley.

Podcasts:

Acknowledgements

"The Crossing" could only be told with the help of many people:

- The more than 80 people touched by the tragedy of Dec. 14, 1961, who agreed to tell their stories.

- Bill and Mary Bohlender, who helped unearth numerous historic documents and provided numerous insights.

- Virginia Shelton and Mary Shelton Shafer, who provided numerous insights and access to attorney Jim Shelton's files.

- Keith Blue, who provided numerous insights.

- Peggy Ford and the staff at the City of Greeley Museums, Barbara Dey and the Hart Library staff at the Colorado History Museum and former Rocky librarian Carol Kasel, who all assisted with research.

Contact the series team

- Reporter: Kevin Vaughan

- Photographer: Chris Schneider

- Video: Tim Skillern & Laressa Bachelor

- Print designer: Armando Arrieta

- Web designer: Ken Harper

- Web producer: Forrest Stewart

- Web developer: Chris Nguyen

- Copy editor: Dianne Rose

- Photo editor: Dean Krakel

- Imager: Marie Griffin

- Interactive editor: Mike Noe

- Project editor: Carol Hanner

Many of those who lived through the tragedy at the crossing credit God. Carolyn Baxter Tucker credits Weld County Judge Roy M. Briggs — and not just because he made a decision that kept her off the school bus that day in 1961.

She was a 14-year-old bundle of trouble that fall, quarreling constantly with her mother, swiping stuff from stores in Greeley, skipping the school bus ride home to stay in town.

It all caught up with her in mid-November.

When it was settled, Judge Briggs sent her to a reform school, starting her life on a new path.

And after her little brother died at the crossing 300 yards from their small, rundown house, the judge stepped in to help her again.

Animals and softball

Jerry Baxter was a boy who loved animals and had a mischievous streak.

At night, he'd sneak his white guinea pig out of its cage and into bed with him.

In the morning, his mother, Ruby, would chew him out.

"Get that thing back in the cage," she would say.

After school, he'd fill bottles with water, put them in his wagon and drag it out to give the calves a drink.

One day, his mother came home and found him riding a calf around the yard.

He was a southpaw with a strong arm who loved to play softball when he could.

Some evenings, he'd nod off on the couch as his dad, Verne, rubbed his back.

"That's enough," Jerry's father would finally say, "now get to bed."

He reminded his older sister, Carolyn, of Dopey, one of Snow White's Seven Dwarfs, the way he'd sleep with his rump sticking up in the air.

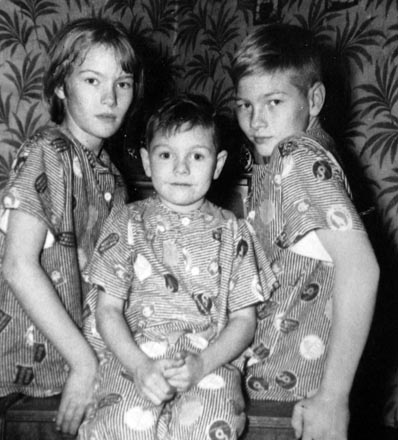

On Dec. 14, 1961, Jerry, a fourth-grader at Delta Elementary, headed out the door of his house, walked directly across the dirty, snowy road and hopped on the bus. He joined his cousins, Calvin Craven, who turned 10 that day, and Ellen Craven, who was 8.

He was the last of 36 children to slip into the green vinyl seats on bus No. 2.

Minutes later, Jerry and his cousins lay dead in the worst traffic accident in Colorado history.

By the time of the crash, Carolyn had been away from Jerry and her home for most of a month.

In the fall of 1961, the 14-year-old had defied her mother constantly.

If she didn't feel like going home when class got out at Meeker Junior High, she didn't get on the bus.

She'd wander around Greeley, meander through the Woolworth's or other stores downtown, where a bottle of Jergens lotion sold for 67 cents and a box of Luden's chocolate-coated cherries sold two for $1.

When she saw something she wanted, she just took it.

It was silly stuff.

At the Woolworth's, she pocketed a deck of pinochle cards. She didn't even know how to play.

Usually, at the end of the day, she'd head to the filling station where her dad pumped gas and catch a ride home.

Then, one day in mid-November, she decided to run away. She went on a shoplifting spree, figuring she needed clothes since she wasn't coming back.

She hopped in a car with another girl, and they sped south out of Greeley. A couple miles away in Evans, the other girl lost control of the car, and it spun to a stop in the middle of the road.

A police officer found Carolyn at a gas station not far away, trying to call a friend for a ride. The officer took her to the police station.

"About the only thing I had on, in the way of clothes and everything, that was mine was my panties and bra, and my heavy overcoat," Carolyn says now. "Everything else I had shoplifted."

"It really shocked the police," she says. "I started taking this stuff off — 'I got this from there, and I got this from there.'"

A few days later, she sat across a table from Judge Briggs.

A sober look on his face, he ordered young Carolyn to a reform school in Denver.

Protection from grief

In the confusion of Dec. 14, 1961, Verne and Ruby Baxter discovered that Jerry was dead.

They wanted to be the ones to tell Carolyn.

They went to the courthouse that afternoon and told Briggs what had happened.

The judge picked up a telephone.

He talked to someone at the reform school, made sure that the televisions and radios stayed off, that the afternoon newspaper was kept away from Carolyn.

And he arranged for her to go home.

In the morning, Verne and Ruby drove to Denver. They sat Carolyn down, told her Jerry was gone and took her back to Greeley.

The next day, a Saturday, they said goodbye to Jerry, Calvin and Ellen in a single service for the three cousins at Macy's funeral home on Seventh Avenue in Greeley. More than 200 mourners filled the chapel while three hearses sat outside, awaiting the three coffins.

That day is a blur in Carolyn's mind now. A crush of people at the cemetery. Her grandmother, kneeling down next to the three caskets, crying. Someone pushing Carolyn's hat back on after it nearly blew off.

A few days later, Carolyn was driven back to Denver to finish her sentence.

"You know, you have time to do a lot of thinking," Carolyn says now. "I was thinking, 'If he hadn't sent me up here I would have been on the bus with Jerry.'"

She soon realized that the judge had protected her from more than an accident. Without reform school, she was headed for a destructive life.

"I'm glad he sent me up here," she thought at one point during her commitment. "He saved me. I'm going to learn something while I'm here."

Months later, when her mother was hospitalized for surgery, Briggs stepped in again, making arrangements to convert Carolyn's sentence to probation so she could go home to her family.

She never saw the judge again after the day he sent her to reform school.

But she never forgot him.

"He cared," she says. "That's the feeling that came across — that he cared about the individual."

He cared especially for children.

Judge Briggs always had a few silver dollars in his pocket, and he doled them out to children he encountered almost daily. When he presided over an adoption, he'd end the proceedings by putting a silver dollar in the child's hand. He bought shoes for needy kids, and one Christmas he even purchased a guitar for a boy who wasn't going to have much else under his tree.

Eventually, Carolyn's juvenile record was sealed, and she was able to sign up for the Army.

Along the way, she made peace with her mother.

When Carolyn was in her late 20s and stationed at Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington, D.C., her parents divorced and her mother came to live with her.

They began to talk — about little things and big things.

She found out that in the last weeks of his life, Jerry shot up in a growth spurt and was about as tall as his mother when he died. She found out that even though her mother always told her "no," it was often her dad who decided she couldn't do things, such as joining the Girl Scouts.

"Why didn't you tell me?" Carolyn asked.

"I didn't think you were old enough to understand," her mother told her.

Carolyn Tucker is a long way from the reform school where she spent seven months, a long way from the incorrigible girl who butted heads with her mother.

Today, she lives in Arizona, about 40 miles from her mother, who battles Alzheimer's disease in a Lake Havasu City nursing home. And she remembers a sober-faced judge who saved her life.

Judge Roy Martin Briggs was 91 when he died on Jan. 11, 1994, in Morrison. But his legacy lives on.

"I think he'd be proud of me," she says.

NEXT: Perspective