Crossing chapters

Jump to:Related content

Crossing forums

Forum at the Rocky Mountain News in Denver.

Forum at the Rocky Mountain News in Denver.

Forum at the Union Colony Civic Center in Greeley.

Forum at the Union Colony Civic Center in Greeley.

Podcasts:

Acknowledgements

"The Crossing" could only be told with the help of many people:

- The more than 80 people touched by the tragedy of Dec. 14, 1961, who agreed to tell their stories.

- Bill and Mary Bohlender, who helped unearth numerous historic documents and provided numerous insights.

- Virginia Shelton and Mary Shelton Shafer, who provided numerous insights and access to attorney Jim Shelton's files.

- Keith Blue, who provided numerous insights.

- Peggy Ford and the staff at the City of Greeley Museums, Barbara Dey and the Hart Library staff at the Colorado History Museum and former Rocky librarian Carol Kasel, who all assisted with research.

Contact the series team

- Reporter: Kevin Vaughan

- Photographer: Chris Schneider

- Video: Tim Skillern & Laressa Bachelor

- Print designer: Armando Arrieta

- Web designer: Ken Harper

- Web producer: Forrest Stewart

- Web developer: Chris Nguyen

- Copy editor: Dianne Rose

- Photo editor: Dean Krakel

- Imager: Marie Griffin

- Interactive editor: Mike Noe

- Project editor: Carol Hanner

Jack Mitchell, a cowboy tough enough to wrestle steers but not his own demons, lost a decades-long battle with the bottle on Nov. 20, 1991.

He was only 57, but his organs could no longer hold up under the punishment they'd endured, and they shut down, and he was gone.

His wife gathered up his belongings, sat down and sorted through them. In his wallet, she came across a small photograph of a 6-year-old girl.

Her name was Sherry.

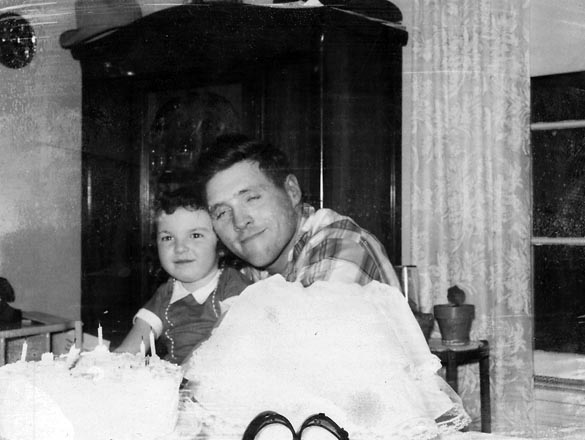

In the picture, Sherry's auburn hair cascaded down in gentle curls, just touching her shoulders. Her bangs hung across her forehead, and her chocolate eyes sparkled. A gentle, innocent smile creased her face, tilted ever so slightly to one side.

She was not Jack's biological daughter, but she had been his little girl.

And she had been taken from him on Dec. 14, 1961, when a train cut through her school bus.

Melting hearts

By the time Jack Mitchell and Joyce Rhoades met, she had already known hard times. She'd endured a broken marriage and had lost a lung to tuberculosis. She'd lost custody of her two sons, but she was raising her daughter, Sherry.

Somehow Jack and Joyce clicked, and they were married. Jack adopted Sherry and gave her his last name.

They moved into an old farmhouse along U.S. 34, and they were a family.

Sherry was the kind of little girl who melted hearts, beginning with Jack's.

He teased her by singing his own version of the popular Kingston Trio song with its incessant "Hang down your head, Tom Dooley" chorus.

He'd say, "Hang down your dooley, Tom," and Sherry would laugh. Then she'd repeat it, and Jack would beam.

Jack couldn't hide his love for her, and she returned the affection, following him around like a happy puppy.

Sherry was his little cowgirl, out in the farmyard with him, riding horses with him.

One day, Jack was outside, castrating pigs, and Sherry was right there with him. A little later, she walked into the house, carrying a bucket.

Joyce asked her what she was doing.

Daddy and I are out there cutting the nuts out of pigs, she said, and her mother just about fainted.

But just when everything was so good, Jack got hurt.

He was working in the stockyards on the outskirts of Greeley when a steer in a cattle pen pancaked him up against a fence. For a time, the doctors weren't sure he would survive. He was still in the hospital on Dec. 14, 1961.

That morning, when the bus pulled up in front of their home, Sherry didn't want to go to school. She wanted to go to the hospital.

I want to be with my daddy, she told her mother.

Joyce said no.

Honey, you've got to go to school so I can be with your daddy, she told Sherry.

She carried her screaming daughter to the bus and said goodbye.

A frantic search

It is difficult to comprehend how awful that day was for the families who had children on the bus.

In the confusion, heartsick mothers and fathers shuttled from the Greeley hospital to the old state armory building on Eighth Avenue to the courthouse, where somber investigators gathered information to identify the dead. Parents who couldn't find their children at the hospital figured they were dead. But at the temporary morgue in the armory, they'd get no answers as the identification of the 20 bodies dragged through the day.

It was no different for those who loved Sherry.

Bill Mitchell, Jack's younger brother, came home to find a note: There'd been a bus-train crash, and Sherry may have been in it. Later, at the hospital with his grandparents — who loved little Sherry as their own great-grandchild — they all hoped for the best. But, as each minute ticked past, their hope dwindled.

The worst came later, when Jack's grandfather went to the armory. He was allowed inside, to the room where 20 bodies were laid out on the floor, each one covered by a blanket. He lifted 17 of those blankets before he found Sherry's body.

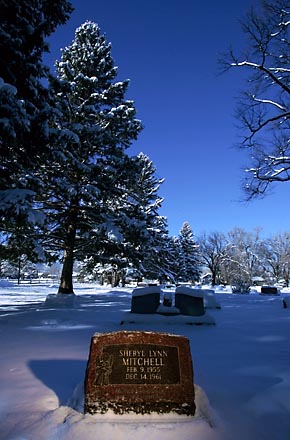

When they said goodbye to Sherry at the Seventh-Day Adventist Church in Fort Collins, and when they buried her in Grandview Cemetery, Jack was still in the hospital.

He recovered physically. But Bill Mitchell believes his brother never recovered emotionally.

"He never brought it up much at all," he says. "That's kind of the way he was — it was over with."

Jack, already fond of liquor, drank even more. Within a year or two, he and Joyce split.

Jack married twice more, but his family is sure he never really found peace. By the end, his younger brother saw a beaten man with little to live for.

Joyce faced more heartache, too.

After her divorce from Jack, she married Clyde Seiler, a pilot for Continental Airlines and a member of the Colorado Air National Guard's 120th Tactical Fighter Squadron. They had a son, Steven, born in 1967.

Clyde's unit was called to active duty in April 1968 and sent to Vietnam.

On March 27, 1969, during a strafing run in his F-100, ground fire tore into his jet. It spun into the ground, killing him instantly.

He was 37 years old. Joyce was on her own again until she met Stan Wood in Aurora in 1974. They married in 1977.

A few years ago, she battled breast cancer.

But despite it all — the loss of Sherry, the death of her husband in Vietnam, the fights against tuberculosis and cancer — she held on. She never felt that her burdens were beyond her, says her oldest son, William Seiler, of McQueeney, Texas, who took Clyde Seiler's name.

"You play the cards that you're dealt," he says. "I think that's what she felt."

Joyce L. Wood died on July 24, 2005, after suffering a stroke. She was 71.

She left to her son William a photograph that had hung in her home for more than 40 years, a picture of a 6-year-old girl, her daughter, Sherry.

The same photograph that Jack Mitchell carried in his wallet until the day he died.

NEXT: Never say never