Crossing chapters

Jump to:Related content

Crossing forums

Forum at the Rocky Mountain News in Denver.

Forum at the Rocky Mountain News in Denver.

Forum at the Union Colony Civic Center in Greeley.

Forum at the Union Colony Civic Center in Greeley.

Podcasts:

Acknowledgements

"The Crossing" could only be told with the help of many people:

- The more than 80 people touched by the tragedy of Dec. 14, 1961, who agreed to tell their stories.

- Bill and Mary Bohlender, who helped unearth numerous historic documents and provided numerous insights.

- Virginia Shelton and Mary Shelton Shafer, who provided numerous insights and access to attorney Jim Shelton's files.

- Keith Blue, who provided numerous insights.

- Peggy Ford and the staff at the City of Greeley Museums, Barbara Dey and the Hart Library staff at the Colorado History Museum and former Rocky librarian Carol Kasel, who all assisted with research.

Contact the series team

- Reporter: Kevin Vaughan

- Photographer: Chris Schneider

- Video: Tim Skillern & Laressa Bachelor

- Print designer: Armando Arrieta

- Web designer: Ken Harper

- Web producer: Forrest Stewart

- Web developer: Chris Nguyen

- Copy editor: Dianne Rose

- Photo editor: Dean Krakel

- Imager: Marie Griffin

- Interactive editor: Mike Noe

- Project editor: Carol Hanner

Thirteen-year-old Cheryl Brown lay in her hospital bed, nasty scrapes on her face, a cut swerving across her right cheek, heavy sandbags jammed up and down her sides to keep her from moving.

It had been four days since she'd climbed onto her school bus, saved a seat for her friend, Nancy Alles, and pulled out a book to study for a social studies test.

Four days since a speeding passenger train had sliced through the bus, hurling her into the middle of a gravel road, paralyzed.

She'd felt utterly helpless, unable to brush the rocks out from beneath her, unable to ward off the bitter cold with her coat bunched up under her arms. She'd turned her head, seen Nancy lying askew on the road, hurt but alive, and wondered why she wasn't pushing her skirt back down.

In the hospital, Cheryl had thrown up so much that the nurses kept a kidney-shaped stainless steel pan on the pillow next to her head.

Her knees and elbows were skinned raw. Her back was broken. She could not move her legs.

A bandage covered a gash in her lower lip. She didn't yet know it, but a surgeon would operate on her lip several times in the coming weeks. Each time, he would extract something new — a hunk of rubber, a piece of gravel, a sliver of glass, part of a tooth.

He started calling it her trash can.

"I wonder what garbage we'll find today," he'd say each time.

But on this day — Dec. 18, 1961 — she lay motionless as Dr. Cloyd Arford, a professional, friendly man with dark brown hair, entered her room.

He stepped up close to her bed.

"Cheryl," he said gently, "we have some bad news."

"What's that?" she asked.

"I'm afraid you're not going to walk again," he told her.

"You're a liar," she blurted.

A day later, a tingle in her legs told her that the feeling was returning. A day after that, doctors put her in a body cast. By the end of the week, she was on her feet, walking.

Many years later, she would summon that same determination — that absolute refusal to believe that the worst might happen — to get through another crisis.

'To my real friend'

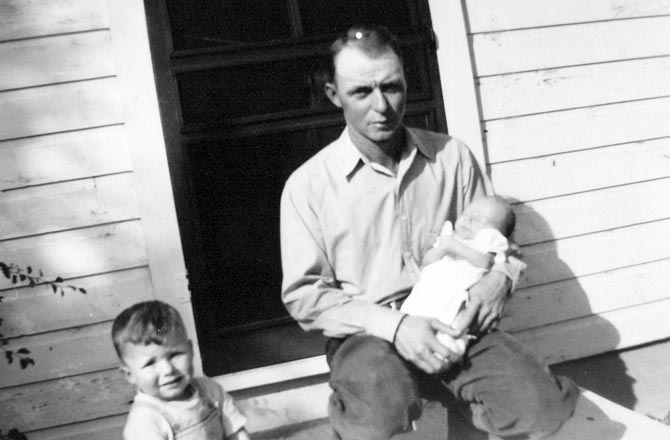

Cheryl's entire childhood unfolded on the 80-acre farm where her parents tended 100 dairy cows. It sat on the corner of two county roads, a half mile from a dairy operated by her grandparents and a mile from the Auburn school.

She grew up with her two brothers: Clarence, who was four years older, and Don, who was six years older.

Her mother was of German descent, her father half-Swedish, half-English. Work and church and 4-H dominated life. Her mother served them sauerkraut and pork with mashed potatoes — one of her dad's favorites — and chicken soup with egg dumplings, and schnit soup, a sweet mixture of apricots, peaches and plums.

After the accident, hundreds of cards poured in from all over the country, from people she never met, from people who simply cared. They were from Paramount, Calif., and Rochester, N.Y., and Raleigh, N.C., and Olathe, Kan.

Many were addressed to her in Room 319 at Weld County General Hospital.

Despite the support and goodwill surrounding her, as Cheryl's body mended, she tried to block out the grief of losing so many friends.

"When I was younger, to keep my sanity, I had to try and forget it, to put it in the back of my mind," she says. "It's hard to have to live with something like that. Because when you think about all the destruction, it hurts to know there was that much pain at that time."

She graduated from high school in Greeley and worked as a licensed practical nurse. She married and moved to Fort Collins, where her husband, Gene Hiatt, worked for Woodward Governor Co.

On March 23, 1976, Cheryl and Gene had a daughter, Katrina.

Today, time has made memories of the accident much easier to bear. She can look at those sympathy cards stored in a sewing table drawer in her basement, some in a small paper sack, others loose.

She can remember the children who died, and now and then, she pulls out a small black-and-white school picture of one of them, Linda Alles.

On the back, Linda had written, "To my real friend."

A daughter in trouble

In the fall of 2002, Katrina Hiatt got sick. At first, it wasn't even enough to interfere with her job tracking computer hardware for the Otis Elevator Co. in Bristol, Conn. Just an innocent, occasional cough. As the days passed, it grew worse.

Several visits to doctors didn't help. Drugs didn't help.

Eventually, doctors considered two possibilities: tuberculosis or cancer.

The test for TB came back negative, so, during the week of Thanksgiving, doctors scheduled exploratory surgery. They removed a lymph node in the 26-year-old's neck and sent it to a lab for tests.

Back in Fort Collins, Cheryl fought fear.

She wanted to be in Connecticut with her daughter, but Katrina persuaded her to wait until she got a diagnosis.

In early December, Katrina went to see her doctor to have the stitches plucked out of her neck.

The doctor told her she had Hodgkin's lymphoma, a cancer of the lymph system. She'll never forget the phrase he used to describe it: "Stage 4A."

Stage 4, as in the final stage of the disease. Bad. A, as in all contained in one place. Good — at least as good as it gets with cancer.

The doctor said her chances of recovery were strong, maybe as high as 90 percent. But not everyone who gets Hodgkin's gets well.

The next day, Cheryl boarded a plane. She moved into Katrina's one-bedroom apartment.

The news stunned Cheryl and Gene. Neither had much history of cancer in their families.

Katrina had been a fiend about staying healthy.

She'd been a ballet dancer, and she thought she was in top physical condition. Now she faced the prospect of a long fight that she might not win.

But, like her mother so many years before her, she had determination on her side.

Fighting again

The Friday before Christmas 2002, Katrina endured her first chemotherapy treatment.

Cheryl spent the next 11 months in Connecticut. Katrina underwent chemo every two weeks, sitting for hours while a toxic mix of drugs dripped into her veins. The mixture killed cancer cells. It also ravaged her immune system.

Cheryl cooked a precise regimen of meals aimed at keeping up Katrina's strength, at keeping her from getting sick.

Cheryl wondered constantly whether her only child would get well. She learned a lot along the way — about Hodgkin's, about things she could do to help her daughter fight it. Even about herself.

Today, Cheryl looks back on that time with a mixture of relief and awe. She is a woman who uses laughter to fight off nervousness or uncomfortable feelings. She is not laughing now.

"You learn that you have to do what you have to do," Cheryl says, "and you can't say, 'Poor me' or 'Woe is me.' You just do it and keep going, because if you don't, she'd never made it. You had to keep saying, 'You're going to get well.'

"And there were times, trust me, after her chemo when I don't think she ever cared if she got well, because of the nausea and everything."

She brushes off comparisons between her daughter's strength and the moxie Cheryl showed when she looked her doctor in the eye and told him he was a liar.

"To me, hers was so much harder of a fight than what I had," she says.

Katrina shrugs it off. "You don't know what you can fight through until you have to," she says.

That year gave Katrina two gifts: her health and a new relationship with her mother.

"How many people as an adult get to know their parents again?" she asks.

Katrina returned to Colorado in December with her boyfriend to spend Christmas with her parents. She brought gifts — a basket of Connecticut wine for her mother; shirts, cologne and a watch for her father.

But there was one gift they all shared that was better than the rest: three years of remission.

NEXT: A Christmas wish