Crossing chapters

Jump to:Video

Duane Harms' life in California hasn't been easy, and he's never put the bus crash completely behind him.

Watch video

Watch video

Related content

Crossing forums

Forum at the Rocky Mountain News in Denver.

Forum at the Rocky Mountain News in Denver.

Forum at the Union Colony Civic Center in Greeley.

Forum at the Union Colony Civic Center in Greeley.

Podcasts:

Acknowledgements

"The Crossing" could only be told with the help of many people:

- The more than 80 people touched by the tragedy of Dec. 14, 1961, who agreed to tell their stories.

- Bill and Mary Bohlender, who helped unearth numerous historic documents and provided numerous insights.

- Virginia Shelton and Mary Shelton Shafer, who provided numerous insights and access to attorney Jim Shelton's files.

- Keith Blue, who provided numerous insights.

- Peggy Ford and the staff at the City of Greeley Museums, Barbara Dey and the Hart Library staff at the Colorado History Museum and former Rocky librarian Carol Kasel, who all assisted with research.

Contact the series team

- Reporter: Kevin Vaughan

- Photographer: Chris Schneider

- Video: Tim Skillern & Laressa Bachelor

- Print designer: Armando Arrieta

- Web designer: Ken Harper

- Web producer: Forrest Stewart

- Web developer: Chris Nguyen

- Copy editor: Dianne Rose

- Photo editor: Dean Krakel

- Imager: Marie Griffin

- Interactive editor: Mike Noe

- Project editor: Carol Hanner

Five days before his 34th wedding anniversary, Duane Harms walked into a California courthouse with his attorney and asked a judge for the legal authority to make decisions for his wife, Judy.

Though he had left Colorado and that awful, cold day at the crossing, he had not left behind anguish.

And though he'd found work as a school district electrician — work that gave him tremendous satisfaction, that made him feel appreciated — he had not left behind personal tragedy.

Judy was mentally ill.

It was not the life he had imagined when they'd married amid white gladioli and red carnations in an evening ceremony on Aug. 22, 1959, in Sterling.

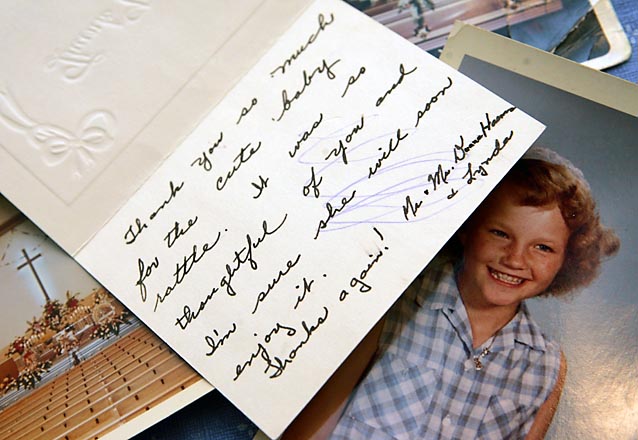

They had a little girl on Nov. 24, 1961, in Greeley and named her Lynda.

Then, just 20 days later, he drove his school bus into the path of a high-speed passenger train.

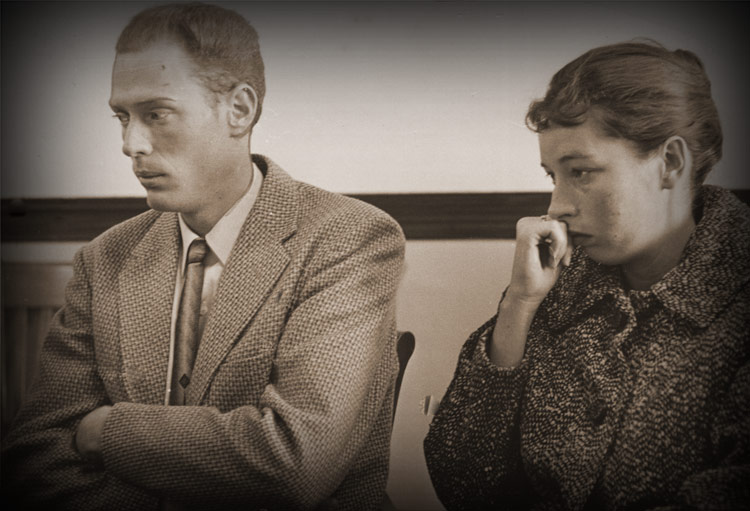

Judy had appeared with him in court, had held his hand. After his acquittal on manslaughter charges, she said goodbye to her family and moved with him to California, where she taught several grades in elementary school. She liked kindergarten the best.

But over the years, she slowly slipped away from him as mental illness overtook her.

The hardships ebbed and flowed. Duane would get her help. She would be better for a while. Then she would slip, and the cycle would start over again.

After more than two decades of struggle, Judy could no longer care for herself.

By 1993, Duane believed the only way to care for Judy was to take control of her affairs and treatment by asking a court to name him as her conservator.

In a motion filed Aug. 17, 1993, Duane and his lawyer summarized Judy's mental state in a few sentences of dispassionate language:

"She had a nervous breakdown and is in poor health. Over the past twenty years, the police have had to come and take her to the mental wards for observation because of her bizarre behavior. She will not let a doctor evaluate her, and when medication was prescribed, she doesn't take it. She has gotten into arguments with employees at three different grocery stores."

Later, they wrote: "She had a nervous breakdown and does not communicate clearly. She has a hard time understanding what is happening around her."

But having the authority to determine Judy's treatment did not mean he could make her follow it. For the next decade, he slept in a separate bedroom, a lock on the door, afraid that Judy might kill him in his sleep. County officials compiled a voluminous file on her.

Finally, in 2003, Duane returned to court. He could no longer care for his wife.

His lawyer, Alan D. Davis, filed a new petition with the court. In it, he wrote of Judy: "In the past, she has been very uncooperative."

"At this point," Davis wrote, "since Mr. Harms is unable to get his wife the medical treatment and assistance she requires, I would suggest that the court terminate his powers, appoint the public guardian, and refer the case to adult protective services."

On May 21, 2003, a judge committed her to a state mental hospital.

Duane seldom sees Judy now. The last few times he visited, she talked of trying to come home. That, he says, is not an option.

"I have my reasons," he says. "You may not understand that, but I have my reasons."

Duane suspects Judy's condition could be genetic — one of her aunts suffered from mental illness.

His voice carries no anger or bitterness. Even when he tells the rest of the story.

Inside his darkened home is his 45-year-old daughter, Lynda, his only child. She, too, is mentally ill.

Her childhood had been normal. Then one summer day after she graduated from high school, Lynda went for a ride with a friend. The friend lost control of her car and smashed into a eucalyptus tree. Lynda's friend was fine. Lynda wasn't. She suffered a broken leg and arm and internal injuries. She spent a week in intensive care and a month in the hospital.

But as she recovered physically, she deteriorated mentally. Duane doesn't know whether the accident caused her mental illness or triggered something already there. Now she seldom ventures from home.

Duane does not blame the girl who was driving the car. An accident, he says, is an accident.

"We just need to trust God and hope for the best — try to live as good a life as we can," he says.

Human nature

Duane can talk about a lot of things, about the softball he still plays, about basketball, about the enjoyment he gets out of rocks and his collection of state quarters.

He can talk about the NBA games he follows and the Detroit Tigers — they were his dad's favorite team, and he likes their caps.

Talking about Dec. 14, 1961, is more difficult.

He still fears for his life. He understands why some people were so angry. They lost children.

"It's human nature," he said.

He has returned to Colorado only two or three times since he left in 1962, the last time for his mother's funeral in June 1989. He did not come back when his father remarried later that year, or for his 40th or 45th high school reunions, or for his father's funeral in 2003.

He is hesitant to talk about the crash because he doesn't want to bring more pain to those who were hurt so badly at the crossing.

But he does think about it. For a long time, it was always on his mind. He eventually faced a choice: Be dragged down forever by the sorrow, or fight through it.

He chose to fight. It makes him feel good, he says, to hear that children who survived the bus accident are doing well. He is pleased to know that Bruce Ford is a five-time world champion bareback rider. Surprised to find that Glen Ford drives a school bus. Relieved to hear that Jerry Hembry — "a really good guy" — is doing well.

He's pleased, he says, to know that people ask about him, wonder how he's doing, wish him well.

None of that lessens the burden he has carried all these years, or makes it any less difficult to erase the nagging thought that someone still might knock on his door and seek revenge for what happened on Dec. 14, 1961.

"People wish they could have a second chance, but it doesn't work that way," he says. "When it's done, it's done."

The image of that destroyed bus, a gaping hole in its rear end, the twisted frame rails protruding, the back wheels torn free, has stuck with him.

When he pictures it in his mind, he can think only one thing: How did anyone survive?

He thinks, too, about the testimony of the train crew that he hadn't stopped at the crossing, and he has a theory on why they thought that. Regulations allowed him to stop as far as 50 feet from the rails, which he thinks he may have done. Stopping there may have obscured his view of the train and blocked the engineer's view of the bus.

He remains grateful that people in his new city accepted him, that the local school district didn't hold the accident against him.

"When I applied at the school district, I didn't even know if they'd want me," he says. "But they were nice enough to give me a job, and it was a wonderful place to work for 38 years."

When he retired, they threw him a party.

Asked if he believes life has been unfair to him, he is understated: "I've had some bumps along the way."

Nobody escapes the hard times that life brings, he believes. But neither is anyone alone.

"There's a Lord God above us looking down," he says.

NEXT: Moving on