Crossing chapters

Jump to:Related content

Crossing forums

Forum at the Rocky Mountain News in Denver.

Forum at the Rocky Mountain News in Denver.

Forum at the Union Colony Civic Center in Greeley.

Forum at the Union Colony Civic Center in Greeley.

Podcasts:

Acknowledgements

"The Crossing" could only be told with the help of many people:

- The more than 80 people touched by the tragedy of Dec. 14, 1961, who agreed to tell their stories.

- Bill and Mary Bohlender, who helped unearth numerous historic documents and provided numerous insights.

- Virginia Shelton and Mary Shelton Shafer, who provided numerous insights and access to attorney Jim Shelton's files.

- Keith Blue, who provided numerous insights.

- Peggy Ford and the staff at the City of Greeley Museums, Barbara Dey and the Hart Library staff at the Colorado History Museum and former Rocky librarian Carol Kasel, who all assisted with research.

Contact the series team

- Reporter: Kevin Vaughan

- Photographer: Chris Schneider

- Video: Tim Skillern & Laressa Bachelor

- Print designer: Armando Arrieta

- Web designer: Ken Harper

- Web producer: Forrest Stewart

- Web developer: Chris Nguyen

- Copy editor: Dianne Rose

- Photo editor: Dean Krakel

- Imager: Marie Griffin

- Interactive editor: Mike Noe

- Project editor: Carol Hanner

Sometimes the most surprising thing about a tragedy is not what it does to people, but what it doesn't do to them.

For three kids pummeled inside their school bus by a high-speed passenger train in 1961, the legacy of the accident is remarkably similar, even though their injuries were decidedly different.

It happened. They recovered. It didn't dramatically alter their lives. One came away with little more than a lost boot, some bruises and scrapes. Another suffered a broken back, but it hasn't slowed him down a bit.

The third — miraculously, the only child in the very back of the bus who survived the collision — almost died and suffered through an excruciating recovery, but, like the others, went on to live a full life.

When they think about that day, they are philosophical. No bad feelings come. When they talk about that day, they are composed.

They don't cry.

Jumbled memories

Randy Geisick wanted to do something special.

Twenty minutes earlier, the 8-year-old had climbed onto his school bus, carrying Christmas paper to wrap a gift he had made in class.

He woke up in the shattered remains of the bus, his left boot gone, his foot freezing. As he worked his way free and stepped out into the chaotic scene, a Union Pacific train sat idling down the tracks.

Someone — he is not sure who — stood on one of the rails, balancing. Randy was worried about him.

"You'd better get off the track," Randy told him. "There's a train coming."

Much of the rest of the day is a jumble of memories. A woman helping him into the back of Joe Brantner's station wagon. His dad and his grandpa meeting him at the hospital.

Someone washing his dirty face with a dripping wet washcloth. His mom crying when he got home a few hours later, virtually unscathed.

His real concern in the immediate aftermath: He had lost his wrapping paper.

Don't worry about it, his relieved mother told him.

As with many of the generation who had lived through the Depression and World War II, the Geisicks didn't talk much about bad things that happened.

When young Randy asked his parents about the accident, he got a simple answer:

A train hit the bus.

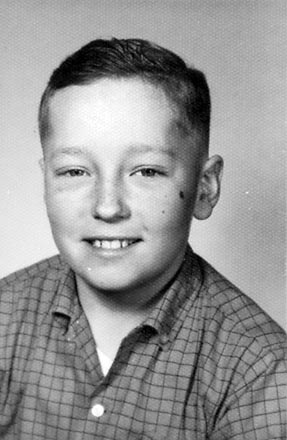

One day at his cousin Ronald's home, the boys got into a closet and found a newspaper with photographs of many of the kids who had been on the bus. Randy's picture was there, but he was misidentified as "Ronald Geisick."

"Look," his cousin said, "there's my name."

Just then, Randy's mother appeared.

"Put that back," she said.

No burning questions

With little conversation about the tragedy, it rarely entered Randy's mind as he grew up.

"I don't remember thinking about it," he says.

After high school, he farmed for a time, worked for a construction company and eventually headed to California in 1983.

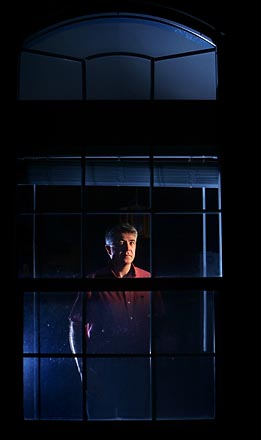

Since 1994, he has lived in Elk Grove, a few miles south of Sacramento, with his wife, Dottie. He is a project manager for a company that makes fixtures for retail stores.

At 53, he is a soft-spoken, thoughtful man with dark hair tinged gray. He still doesn't know much about the accident. In the past 10 years, he has poked around a little bit on the Internet to see what he could find.

But he's not haunted by any burning questions.

It just didn't affect him that much.

He saw a much greater impact on his parents, who grew more cautious, so protective he sometimes felt smothered.

He remembers the admonitions. Don't get too close to the ditch. Be careful. Don't do this. Don't do that.

When his mother could see him, he didn't dare go high in the air on a swing and jump off, the way his friends did.

As he talks, the unmistakable shriek of a train whistle rises in the distance, coming from the tracks that run a couple blocks away. It doesn't bother him.

"I kinda like it," he says.

Happy to be alive

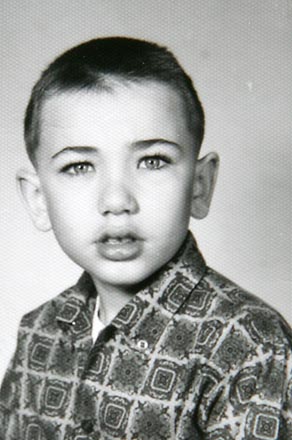

Alan Stromberger was 11 on that wintry December day when he took a seat near the front of the bus.

He awoke on the ground, crawling among the scattered papers and debris, unable to walk because his back was broken.

A county dump-truck driver picked him up and put him in the front seat of his rig, by the heater, so he could warm up.

The next thing he knew, he was in someone's car, racing to the hospital.

He spent a month there recovering from several broken vertebrae.

Today, he is a 56-year-old farmer, living in Iliff, about 10 miles from where school bus driver Duane Harms grew up.

Alan thinks about the accident once in a while — when he sees children stepping onto a school bus, when Dec. 14 rolls around.

And yet, like Randy Geisick, he is not fixated on it.

He considers himself fortunate — if he saw anything gory that day along the tracks, he does not remember it. He considers himself lucky to be alive. Beyond that, he sees little impact on his life.

"I feel like it really hasn't affected me that much," he says.

His back injury was serious, to be sure. But it was nothing compared with what his little sister went through.

Screaming in pain

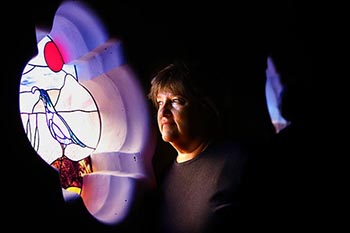

Seven-year-old Debbie Stromberger, Alan's sister, hurried to a seat in the very back of the bus and slipped her galoshes on over her shoes.

Less than 20 minutes later, she was in a fight for her life.

When the fast-moving train plowed into the bus, it sheared off the last few feet, taking four seats with it and the children who sat in them.

Debbie was the only one of those children who survived.

But it was close.

She suffered a severe concussion and a broken leg and hand. Her spleen ruptured. She stopped breathing, and doctors had to perform a tracheotomy to keep her alive.

She endured a grueling recovery, beginning with 10 days in a coma. Doctors weren't sure she would ever get better. She spent a month in the hospital, her leg in traction, and pain clawed at her constantly. It was so bad she'd just scream.

She'd lie in bed and hear the X-ray machine clattering down the hall toward her, and she knew it meant they'd have to move her, and she'd scream some more.

When she finally got home in mid-January, in a body cast, a pin through her leg, she was greeted by the Christmas tree, all dried and shriveled.

She spent the rest of that school year at home, learning from a tutor, feeling overwhelmed by all the gifts and cards that came.

And she got better.

Today, Debbie Stromberger Keiser lives in Wickenburg, Ariz., on a small acreage with her husband, Dale. He is a consultant, specializing in hospital laboratory equipment. She helps with the business.

She is scarred physically — on her throat where doctors inserted the tracheotomy tube, and on her leg.

People see the scars and ask her what happened.

"Then I'll explain the whole story," she says, "and they'll say, 'That's a really tragic thing.'"

But she has no physical hangover from all the injuries.

"I really don't," she says. "I'm very fortunate. I was so young, hopefully things will hold together pretty good. I really don't have anything that I could say is because of that."

The accident was, she believes, just something that happened — not the bus driver's fault, not anybody's fault.

"It's not something that really hangs with me, I guess," she says. "I just kind of have gone on."

Finding peace

Three people, all with a tranquility about a tragic day in their lives.

But for some, peace never came.

NEXT: Heartbreak