Crossing chapters

Jump to:Related content

Crossing forums

Forum at the Rocky Mountain News in Denver.

Forum at the Rocky Mountain News in Denver.

Forum at the Union Colony Civic Center in Greeley.

Forum at the Union Colony Civic Center in Greeley.

Podcasts:

Acknowledgements

"The Crossing" could only be told with the help of many people:

- The more than 80 people touched by the tragedy of Dec. 14, 1961, who agreed to tell their stories.

- Bill and Mary Bohlender, who helped unearth numerous historic documents and provided numerous insights.

- Virginia Shelton and Mary Shelton Shafer, who provided numerous insights and access to attorney Jim Shelton's files.

- Keith Blue, who provided numerous insights.

- Peggy Ford and the staff at the City of Greeley Museums, Barbara Dey and the Hart Library staff at the Colorado History Museum and former Rocky librarian Carol Kasel, who all assisted with research.

Contact the series team

- Reporter: Kevin Vaughan

- Photographer: Chris Schneider

- Video: Tim Skillern & Laressa Bachelor

- Print designer: Armando Arrieta

- Web designer: Ken Harper

- Web producer: Forrest Stewart

- Web developer: Chris Nguyen

- Copy editor: Dianne Rose

- Photo editor: Dean Krakel

- Imager: Marie Griffin

- Interactive editor: Mike Noe

- Project editor: Carol Hanner

Sometime around 6 a.m. on Nov. 20, 1965, the Union Pacific's City of Denver streamliner roared past the place where 20 children had died. Herbert Frank Sommers manned the lead engine.

Though he was 68, Herb still rode the rails, still guided thundering diesel locomotives up and down the tracks. Still worked the stretch where he had seen utter horror on Dec. 14, 1961, the day his engine slammed into a school bus, tearing it to pieces.

That crossing had been like thousands of others in rural America — a dirt road with only a railroad "crossbuck" sign along the track, a place of tremendous danger for motorists and train crews alike.

Every crossing like that one was a potential nightmare for engineers like Herb. Cars could go wherever a driver pointed them. Trains could go only where the tracks took them. Cars could stop quickly — in a few hundred feet, even at high speed. A fast-moving train could take hundreds of feet just to slow from its cruising speed and as much as a mile to come to a stop.

On this day, nearly four years after the deadliest traffic accident in Colorado history, everything looked the same except the road, which had been moved. Traffic now crossed the tracks at a different place.

It was five days before Thanksgiving. Herb had only an hour to live.

Hot, dirty work

Born in Cass County, Ind., Herb came to Denver as a boy with his parents, a sister and two brothers. His father sold real estate.

Herb's parents died when he was a teenager, but he stayed in Colorado while his younger brother and sisters moved back to Indiana to live with relatives.

The Union Pacific hired Herb on Oct. 12, 1918, and he went to work as a fireman. He was 21 years old.

He married Anna Sack Miller in Littleton on June 13, 1922.

His early years with the railroad were trying. When there wasn't enough work, he was furloughed — "suspended" in railroad talk. When things picked up, he was recalled.

Union Pacific suspended and recalled him 11 times during his first 17 years on the job. But he stuck with it, and on Oct. 1, 1941, the railroad promoted him to engineer.

The work could be hot and dirty. And dangerous.

A few miles outside Sterling, Herb was at the throttle of a freight train when an axle snapped in the middle of the night on Feb. 27, 1953. Eleven cars jumped the rails, tearing out more than a quarter mile of tracks.

On the fall morning of Sept. 23, 1954, Herb was backing a steam locomotive down the tracks outside the tiny town of Atwood in Colorado's northeast corner.

The engine pulled a line of 15 cars loaded with crushed rock. It was a work train, moving about 20 mph toward a repair job.

A few minutes after 8 a.m., 26-year-old Donald Welch slid behind the wheel of his butane tanker truck, waved goodbye to his two children and drove right into the path of the train. The engine slammed into the cab of the truck, crushing it and killing Welch.

Another time, Herb was headed west near Firestone when a car smashed into the side of his freight train. Two of the three men in the car died.

All of those crashes were horrible. But none approached the scale of what happened on Dec. 14, 1961, when the City of Denver, with Herb at the controls, tore through that school bus a few miles from Greeley.

After the collision, after the train stopped nearly a mile down the rails, Herb pulled on his jacket and clambered out of the cab of his locomotive to find other members of the crew, to tell them they'd hit a school bus.

He met the conductor, Raymond W. Courtney, along the tracks.

They decided to back the train down the tracks, to try to find a telephone. Herb moved the train, stopping a few hundred yards from the remains of the bus. Other crew members rushed back with blankets to cover the dead, while Herb stayed with his locomotive.

An hour later, authorities told Herb to go ahead and take the train and its passengers to Denver. Once there, he and the train crew got into cars and drove to Greeley for an early-afternoon hearing in a third-floor courtroom, organized so prosecutors could take testimony to try to determine exactly what happened.

As Herb sat in the courtroom, he still wore his railroad overalls, his plaid shirt buttoned at the neck.

His thinning hair was combed back neatly. He wore glasses.

"I was absolutely helpless," Herb told reporters. "There was nothing I could do."

He was sure that bus driver Duane Harms had not stopped before pulling in front of his locomotive. He was just as firm during Harms' trial a few months later, when the bus driver was acquitted of manslaughter.

Back to work

As shook up as Herb was, railroading was the only life he knew. He went back to work.

He had reached an enviable position. As a senior engineer, he had his choice of the best jobs. And working a streamliner was the envy of young engineers.

Well before dawn on Nov. 20, 1965, Herb awoke in Sterling, met the City of Denver at the station, climbed into the cab and began the final leg of the overnight Chicago-to-Denver run.

By 6 a.m., he was just outside Greeley, where the train had hit the bus. An hour later, he was closing in on Denver.

At 7:07 a.m., as the City of Denver streaked along at more than 70 mph, the lead locomotive approached a crossing at East 96th Avenue in Adams County. Herb was eight miles from Union Station.

A gasoline tanker truck, freshly loaded with more than 9,000 gallons of fuel, jerked onto the tracks. It was halfway across when Herb's locomotive slammed into it.

The impact ruptured the tanker, splashing a wave of gasoline over the lead engine and throwing the 40-year-old truck driver, Neal E. Davis, into a ditch. In an instant, a fireball shot from the locomotive, and flames raced through the brown grass along the tracks.

The erupting fuel sent a shudder through a shed at the Denver Products Terminal, 150 yards from the tracks, and plant worker Willard C. Livermore rushed to the window.

"At first I thought it was an earthquake, but when I looked out the window, all I could see was fire and smoke," Livermore said.

"The train was still moving down the tracks. Its front was a huge ball of fire which flared out down about one-third of the length of the train."

Livermore ran for the crossing.

Raymond W. Courtney, the conductor who'd also been on the train that hit the school bus, felt a "slight bump."

"Passengers had a funny look on their faces," he said. "Then I turned around and looked up toward the front of the train, and I saw a wave of flames."

The train slowed to a stop nearly a mile from the spot where it had plowed into the tanker.

Livermore found Davis on the ground, about 20 feet from the cab of his truck, severely burned. The flames had seared the clothes off Davis. Only his belt and the soles of his shoes remained.

Firefighters rushed to the fiery locomotives at the head of the train, dousing the fire that remained. When they climbed into the charred cab of the lead locomotive, they found Herb and his fireman, 54-year-old Robert Nalty, the father of three daughters, dead.

Three days later, Herb was buried in Fairmount Cemetery.

Seven days later, Davis, the truck driver with a wife and three children, died at Colorado General Hospital.

A loss too great to bear

The pain of losing her husband of more than 43 years swallowed Anna Sommers.

On Feb. 11, 1966, she carefully composed two letters. One was addressed to her sister and brother-in-law, Helen and Ryman Linge. The other was written to Herb's younger brother, Daniel.

The widow assured everyone she loved them.

She apologized for what she was about to do. She talked about how much she missed Herb. She detailed the type of funeral she wanted — just like Herb's.

She said her attorney could handle all the details. She laid out the diet of her dog, Duke, and asked two friends to take care of him. Then she took a .38-caliber snub-nosed revolver and shot herself in the head.

On Valentine's Day 1966, mourners gathered at a memorial service for Anna at the Moore Memorial Chapel on Clarkson Street in Denver.

It was the same building where they had said goodbye to her husband less than three months earlier.

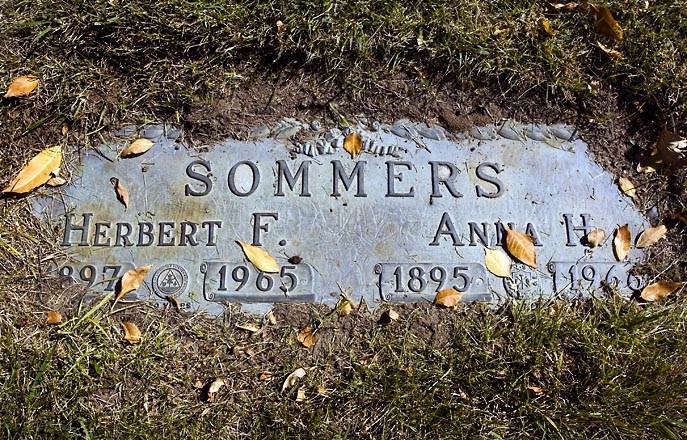

Anna was taken to Fairmount Cemetery, where she was buried next to Herb beneath a headstone with a bronze medallion bearing the crest of the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen and Enginemen.

NEXT: Pushing on