Crossing chapters

Jump to:Video

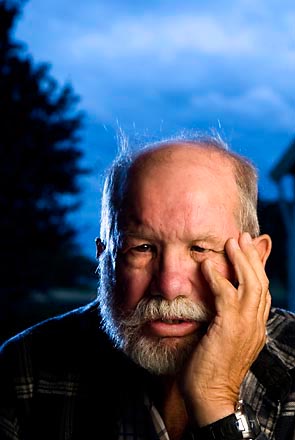

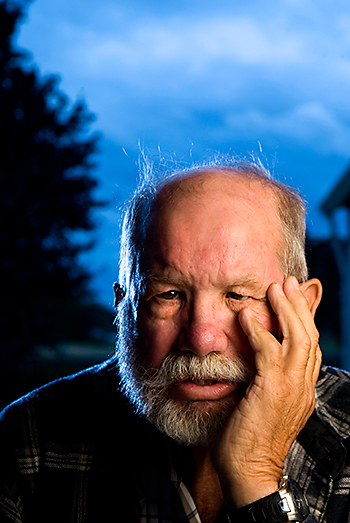

Jerry Hembry pushed on after surviving the crash, and he has persevered through tough times.

Watch video

Watch video

Related content

Crossing forums

Forum at the Rocky Mountain News in Denver.

Forum at the Rocky Mountain News in Denver.

Forum at the Union Colony Civic Center in Greeley.

Forum at the Union Colony Civic Center in Greeley.

Podcasts:

Acknowledgements

"The Crossing" could only be told with the help of many people:

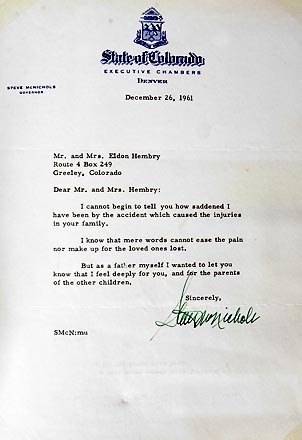

- The more than 80 people touched by the tragedy of Dec. 14, 1961, who agreed to tell their stories.

- Bill and Mary Bohlender, who helped unearth numerous historic documents and provided numerous insights.

- Virginia Shelton and Mary Shelton Shafer, who provided numerous insights and access to attorney Jim Shelton's files.

- Keith Blue, who provided numerous insights.

- Peggy Ford and the staff at the City of Greeley Museums, Barbara Dey and the Hart Library staff at the Colorado History Museum and former Rocky librarian Carol Kasel, who all assisted with research.

Contact the series team

- Reporter: Kevin Vaughan

- Photographer: Chris Schneider

- Video: Tim Skillern & Laressa Bachelor

- Print designer: Armando Arrieta

- Web designer: Ken Harper

- Web producer: Forrest Stewart

- Web developer: Chris Nguyen

- Copy editor: Dianne Rose

- Photo editor: Dean Krakel

- Imager: Marie Griffin

- Interactive editor: Mike Noe

- Project editor: Carol Hanner

Jerry Hembry knows what it's like for a routine moment to turn hellish. He found out the first time in 1961 on a wintry day outside Greeley. He found out again 15 years later, in the fall of 1976.

He stood on a steel catwalk above boilers 2 ½ stories tall, looking over the tangle of pipes that fed chemicals into the beasts. Asbestos insulation wrapped one pipe about 2 inches in diameter.

Jerry didn't touch anything on that catwalk at the Veterans Administration hospital in Vancouver, Wash. He just looked.

Without warning, the 2-inch pipe ruptured. Caustic soda — lye used to treat water — spurted onto Jerry's face, into his left eye, into his mouth, soaking his clothes.

He screamed. He quickly fumbled down from the catwalk to an emergency shower, trying to strip off his clothes, trying to get the burn off him.

Another maintenance man stopped him. Just get under the shower, the man said.

My wallet, Jerry said. I can't get it wet.

Forget your wallet, the man said.

After the water streamed over Jerry for a few minutes, the man grabbed him, carrying him piggyback upstairs into the hospital.

Doctors and nurses swarmed around him. They smeared a cream on his face, trying to cool the burn and stop the damage. His skin was so hot, the cream melted.

That night, a friend visited. Jerry's head had swollen to the size of a five-gallon bucket.

He spent the next nine months in the hospital. The lye had destroyed his left eye and ravaged the muscles inside his mouth.

It also took his confidence. Each day, he worried that some other freak thing would happen, and eventually he sought early retirement from a job he loved. His work for the federal government, which began with a stint in the Navy in Vietnam, ended in 1980 when his retirement request was granted.

But he tried to hold on. Just as he tried to hold on after the ugly divorce that led to a long estrangement from his sons. Just as he tried to hold on as a kid after a train tore into his school bus.

From Colorado to Vietnam

The youngest boy in a farm family with 11 kids, Jerry moved in with one of his mother's cousins when he was a teenager.

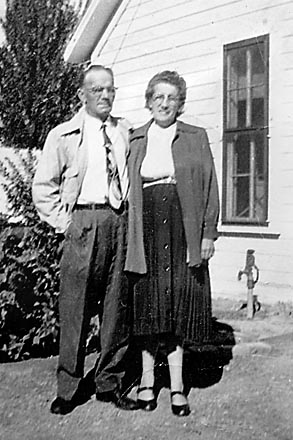

Genevieve Yetter and her husband, Eldon, were raising their two daughters, Colleen and LaDean, on a 160-acre farm down the road from the Auburn school.

Jerry liked the farm life, liked milking the cows and separating the cream and feeding the hogs, liked watching as alfalfa and corn and oats sprouted from the ground.

He wrestled on the high school team, and he worshipped with the Yetters.

On the evening of Dec. 13, 1961, Eldon and Genevieve drove the children to a church rehearsal in Gilcrest and got home late. Colleen and LaDean weren't ready the next morning and missed the school bus.

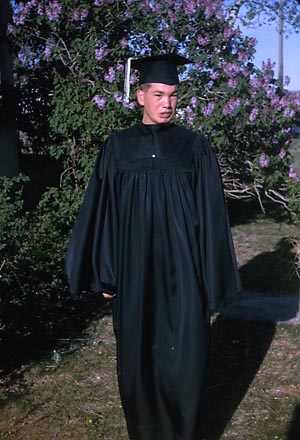

But not 16-year-old Jerry. He saw the yellow bus at the end of the long, curving driveway, and he grabbed his jacket and ran for it.

He jumped into the front seat, just behind the door. He sat there as the bus meandered along the county roads, picking up one child and another and another.

Jerry remembers exactly what happened at 7:59 a.m. He looked out the window as the bus crossed the tracks and saw a big yellow train coming at them. He grabbed the pole next to him and yelled, "Train!"

A moment later, he was rolling through a ditch, bodies of children all around him, his shoulder dislocated, his collarbone broken, cuts and bruises everywhere. He gathered up nearby children and led them to a farmhouse a quarter mile to the west.

For a time, the accident dominated Jerry's life. His injuries ended his wrestling season.

The Yetters already had planned to move the week after Christmas to a new spread a few miles away, but it wasn't far enough. One day, right outside the barn, a father who'd lost a child wanted to know why Jerry had lived.

Another day, an insurance agent came with a check — money Jerry didn't want. The Yetters put it in a trust fund for him.

In the spring of 1962, Jerry testified for the school bus driver, Duane Harms, telling the jury the driver did stop, did open the door, did look and listen before driving onto the tracks.

As soon as he could, Jerry left Colorado.

He enlisted in the Navy in 1964, a few months after graduating from Valley High in Platteville.

He spent parts of 1965 and 1966 on a tanker in Vietnam, hauling fuel up the Mekong Delta. It wasn't exactly combat, though his ship often came under fire and sometimes needed gunboat escorts.

In 1968, he left the Navy and went to work for the VA in Palo Alto, Calif., where he became a plant operator and all-around maintenance man. He later moved to the VA hospital in Washington.

He struggled along through every bad moment, from the chemical accident to his unplanned retirement. And he lived through a nasty divorce. The last time he saw his twin sons together, they were 7 years old.

Scrapbooks and tears

On the covered deck alongside Jerry's mobile home, six wind chimes clatter and clang on a breezy afternoon.

The oldest child on bus No. 2 is now 61 years old.

He has ruddy skin and thick fingers. Most of the hair is gone from the top of his head, and what remains is snowy white. A bristly beard covers his face.

It's difficult to tell, without really studying it, that his left eye is fake. Or that the scarred muscles in his mouth are tight, that he can't quite press his upper and lower lips together.

After retiring from the VA, he found a new job as a maintenance man. Since 1997, he's taken care of Our Lady of Lourdes school in Battle Ground, Wash.

He built his deck. He built a gazebo in the yard.

He does fix-it work — one day, he replaced a neighbor's faucet and accepted a cherry pie as payment.

As he sits on the deck, he flips through two scrapbooks.

One is maroon, with tattered edges and white tape patching the cover. Pasted on its yellowing pages are neatly clipped news articles about the crash. A picture shows Jerry, in a hospital bed, his cousins next to him.

The other scrapbook is red. A strip of yellowing tape holds his light blue hospital wristband on one page. Pasted on other pages are cards from well-wishers. As Jerry thumbs through the book, he comes to a card with James Arness as Gunsmoke's "Matt Dillon" and the words "Git Well Soon" on the cover.

He chuckles.

When he talks about the crash, he closes his eyes, fighting to hold back the tears. They come anyway.

"I just don't understand," he says, emotion straining his voice, "why I was allowed to live."

But he does not dwell on the bus crash, or the chemical explosion, or the divorce.

He is content on his porch, accepting of his life.

His girlfriend lives a few doors down. They hike and camp, ride horses, garden — she grows zucchini and he grows strawberries.

"I don't think I've been slighted or cheated or anything," he says. "I think I've been very lucky in terms of the things I know, the friends I've got."

He knows good things can happen even after bad.

On a spring day in 2005, he came home to find a message on his answering machine.

Terry, one of his twin sons, had called.

For a moment, Jerry thought it was a prank. Then he picked up the phone. Since then, the two have rebuilt a relationship damaged by years of separation.

Jerry has been to Alaska, where he went snowshoeing with Terry. Terry has been to Battle Ground. They talk frequently.

"It puts you on a great high," Jerry says.

He hasn't yet visited with his other son, Gerry. There's still a distance between them.

But he's going to push on, just as he always has.

NEXT: Complicated grief