Click and drag image

Crossing chapters

Jump to:Documents & related links

Chapter 1 documents

- School bus brochure from Weld County District Attorney's Office file

- Portions of Colorado school bus regulations, 1959, from Weld County District Attorney's Office file. Underlines and notations by DA's office.

Related links

Related content

Crossing forums

Forum at the Rocky Mountain News in Denver.

Forum at the Rocky Mountain News in Denver.

Forum at the Union Colony Civic Center in Greeley.

Forum at the Union Colony Civic Center in Greeley.

Podcasts:

Acknowledgements

"The Crossing" could only be told with the help of many people:

- The more than 80 people touched by the tragedy of Dec. 14, 1961, who agreed to tell their stories.

- Bill and Mary Bohlender, who helped unearth numerous historic documents and provided numerous insights.

- Virginia Shelton and Mary Shelton Shafer, who provided numerous insights and access to attorney Jim Shelton's files.

- Keith Blue, who provided numerous insights.

- Peggy Ford and the staff at the City of Greeley Museums, Barbara Dey and the Hart Library staff at the Colorado History Museum and former Rocky librarian Carol Kasel, who all assisted with research.

Contact the series team

- Reporter: Kevin Vaughan

- Photographer: Chris Schneider

- Video: Tim Skillern & Laressa Bachelor

- Print designer: Armando Arrieta

- Web designer: Ken Harper

- Web producer: Forrest Stewart

- Web developer: Chris Nguyen

- Copy editor: Dianne Rose

- Photo editor: Dean Krakel

- Imager: Marie Griffin

- Interactive editor: Mike Noe

- Project editor: Carol Hanner

A slender school bus driver with a sun-beaten face and cowboy hands pulls up to the tracks.

It is the first of 29 times he will navigate railroad crossings on this day in the cornfields and pastures of rural Weld County, close to the farm where he grew up.

It is the first of 29 times he will flash back to a frigid morning from his childhood, to a lonely crossing that cuts through his memory, to tragedy.

"That train came up through there that day," he says, peering out into a cold, dreary drizzle.

He slides open a window to his left, pushes a button next to his seat. The door pops open in a blast of air.

He listens for the shriek of a train whistle, for the rumble of a locomotive. He searches for the piercing beam of an engine's headlight, for movement on the rails, for trouble.

The emergency flashers on the bus blink. Click. Click. Click. A row of grain cars sits idly on an adjacent rail line. A pickup's headlights puncture the gloom in the distance.

Down the misty tracks, he sees nothing, hears nothing.

In his mind, he sees back to 1961, to the day a yellow Union Pacific passenger train, streaking down these same tracks at close to 80 mph, slashed through a school bus less than five miles away.

To the explosive collision that hurled 20 children, including his brother, to their deaths.

In his mind, he hears a farmer's voice, telling him he'll be all right.

He was 11 years old that day. He is 56 now. After a moment at the crossing, he slides the window closed, hits a switch to his left. The door snaps shut. He steps on the accelerator, and the bus groans forward.

Dec. 14, 1961. The yellow school bus grinds along a crumbly dirt road, moving through the Auburn farming community five miles outside Greeley. Frost coats its windows after a night out in the cold.

For generations, the farm kids had walked to the three-room Auburn school. But now it was closed. Now they had to climb up the steps of the bus, had to slide into its green vinyl seats for a roundabout ride to the schools in town.

In the conference room of an administrative building a few miles outside Cañon City, a man sits beneath two inspirational posters, tears in his eyes.

With neatly combed salt-and-pepper hair and wire-framed glasses, he looks like he should be standing in a classroom. And for much of his adult life, he was a teacher.

Shop was his thing, and there among the lathes and the mills and the drill presses, he was alive, guiding his students, helping them build something functional, maybe even beautiful.

It was the reward of putting himself through college, of fighting and clawing to get off the 320-acre farm where he grew up with a bushel of brothers and sisters and more heartbreak than anyone should be asked to endure.

Outside the window is a tall silver fence, topped with coils of glistening razor wire.

On one side of his green pullover shirt is a little clear pocket with a white tag tucked inside.

He is prisoner No. 83609, and he's more than 12 years into a 40-year sentence because of what happened on Dec. 14, 1992, the anniversary of the worst traffic accident in Colorado history.

The day he drove to school with bloody bedsheets in his pickup. The day a police officer handcuffed him and took him to jail.

But he is not thinking about that, not just now.

He is thinking of that December morning from his childhood, when a speeding train tore into a school bus a few miles from Greeley. He is asked if he would be in prison now if it weren't for what happened on that day in 1961.

"Your whole life could have been different," he says.

Dec. 14, 1961. Inside the small brick house, three rough-and-tumble boys shovel cereal into their mouths, anxious to get going. Normally, before leaving for school, they kneel on the kitchen floor with their mother for prayer. This day, there isn't time.

One of the boys goes to the front window and peers past the trellis outside.

"Here comes the bus," he calls to his brothers, and they are out the door, running for the corner, sack lunches in their hands.

A woman in a pink plaid blouse gently runs her fingers back and forth along the faint horizontal cleft beneath her mouth.

She feels a small lump, a piece of metal or glass — a physical reminder of her injuries.

That's the easy part — finding the bump beneath the skin. What's harder is answering the questions that have surfaced through the years.

She sits in the big, sunny living room of her longtime home on the edge of Greeley, silent for a moment, searching for the words that might help explain that day.

The day she got up from her seat at the back of the bus and moved forward. The day her little brother moved from the front to the back. The day she lived and he died.

The day her two friends — one sitting on either side of her — lost their lives.

"It's like, why did I live and why did they die?" she says.

"Especially my friends I was sitting with that day. Why was I the one to live of the three of us?"

She stares off for a moment.

"I don't think that you can prevent those thoughts from happening," she says.

"What prompted Steven and I to almost literally trade places on the bus in two stops? It's like, why did we move? You just wonder."

A few moments later, she is quiet. "Why were we prompted to change places?" she asks.

"Why was it me who lived, and he died?"

She looks away, sits in silence, unable to find an answer.

Dec. 14, 1961. The City of Denver streamliner rushes toward Auburn at 80 mph.

A noisy, powerful beast stretching 1,540 feet, she thumps past lonesome fields and quiet towns.

Inside, she carries 173 passengers on the last leg of the overnight trip from Chicago to Denver. Some of them head for the dining car to eat breakfast in luxury, with pressed tablecloths and gleaming china.

But the City of Denver's brute strength and her mechanical beauty cannot change one thing: She is late.

A lanky man in a Detroit Tigers baseball cap stands on the front porch of a simple white home in Southern California.

He offers a faint smile and a firm handshake.

After that awful day at the crossing, he ran from the death and the sadness and the bad feelings, fled Colorado, fled heartbreak. But heartbreak chased him down.

Today, in what should be a comfortable life with his wife, he seldom sees her. She is confined to a mental institution, often unaware of what is going on around her, unwilling to take medication that might make her more rational.

His grown daughter spends her days inside his darkened home, behind the curtains drawn tight. Mental illness has hold of her, too, and she rarely ventures outside.

"We all have our struggles," he says.

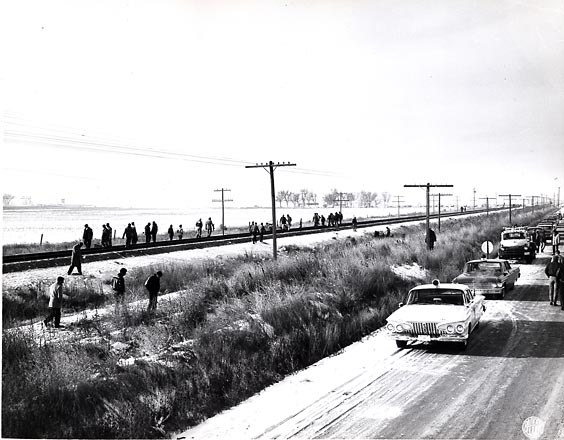

All of these people are strangers, really. Yet they are bound by the same moment in the brown farm fields southeast of Greeley, in a place called Auburn, at the crossing. Even now, the pain of that day is difficult to comprehend.

Five families lost two children each, and two of those families had no other kids. Cousins died. One boy's life ended on his 10th birthday. Brothers and sisters lived, while their siblings perished.

For those left behind, that dark day reverberates in different ways. Some can't talk about it without feeling the burn of tears in their eyes.

Some remember it with a detachment almost devoid of emotion, as though it happened to someone else.

Some give it credit for helping them do good things in their lives.

But no matter where they are and what they do, they all wonder the same thing from time to time:

How would things be different if the train hadn't hit the bus?

They all have moments when a locomotive's shrill whistle or a bright yellow school bus takes them back. Back to a wintry morning outside Greeley, when snow powdered the ground, a haze hung in the early-morning light and the temperature hovered at 6 degrees. Back to the day a sleek, speedy passenger train and a boxy, slow school bus both headed west.

Back to a Thursday. To Dec. 14, 1961.

NEXT: Six degrees