Crossing chapters

Jump to:Documents

Chapter 8 documents

Related content

Crossing forums

Forum at the Rocky Mountain News in Denver.

Forum at the Rocky Mountain News in Denver.

Forum at the Union Colony Civic Center in Greeley.

Forum at the Union Colony Civic Center in Greeley.

Podcasts:

Acknowledgements

"The Crossing" could only be told with the help of many people:

- The more than 80 people touched by the tragedy of Dec. 14, 1961, who agreed to tell their stories.

- Bill and Mary Bohlender, who helped unearth numerous historic documents and provided numerous insights.

- Virginia Shelton and Mary Shelton Shafer, who provided numerous insights and access to attorney Jim Shelton's files.

- Keith Blue, who provided numerous insights.

- Peggy Ford and the staff at the City of Greeley Museums, Barbara Dey and the Hart Library staff at the Colorado History Museum and former Rocky librarian Carol Kasel, who all assisted with research.

Contact the series team

- Reporter: Kevin Vaughan

- Photographer: Chris Schneider

- Video: Tim Skillern & Laressa Bachelor

- Print designer: Armando Arrieta

- Web designer: Ken Harper

- Web producer: Forrest Stewart

- Web developer: Chris Nguyen

- Copy editor: Dianne Rose

- Photo editor: Dean Krakel

- Imager: Marie Griffin

- Interactive editor: Mike Noe

- Project editor: Carol Hanner

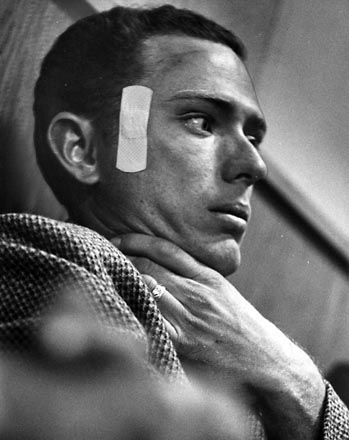

A few hours after a train sheared his school bus in two, after doctors patched up the gash in his leg and stuck a Band-Aid on the cut near his temple, a shocked and bewildered Duane Harms sat down in a room at the Weld County Sheriff's Office.

He faced a crew-cut young deputy district attorney named Bill Bohlender. A court reporter sat nearby, his fingers on the keypad.

Bohlender was ready to go over every moment of the deadliest traffic accident in Colorado history. It was five years before the landmark U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Miranda vs. Arizona, and Bohlender did not tell Harms that anything he said might be used against him in a trial. Bohlender just started asking questions.

Harms recounted every detail, but he wavered on one question: Did you stop at the crossing before driving onto the tracks?

"I always stop at that crossing," Harms said. "That's why I think I did this morning."

They went over it again and again.

"I'm quite sure I stopped, but I wouldn't swear to it because I just don't remember that well," he said. "I always stop."

He talked about the view at the intersection.

"I looked left," Harms said. "That's not hard ... I looked right. It's hard to see ... There are some poles there, and you have to look back over your right shoulder to see the tracks. The windows were frosted ... but there was a little space in the upper part I could see through the rearview mirror."

Bohlender asked Harms if his view was obscured.

"Well," Harms replied, "I should say yes, that's true. Yes, because actually I should have gotten clear out, because it's at such an angle there that in order to see anything at all a fellow should get out of the bus."

Have you ever gotten out before?

"No," Harms said. "The only thing I've ever done is open the door and wait to see if I could hear anything."

The interview ended. Harms, the father of a 3-week-old daughter, was released to the custody of his parents and the family's minister.

A matter of record

At 1:45 p.m., in a third-floor courtroom at the Weld County courthouse in Greeley, prosecutor Karl Ahlborn opened a hearing on the crash. No one had been charged, but he wanted to get the basic facts on the record.

The room teemed with reporters, photographers, gawkers, the first state trooper on the scene, the crew of the Union Pacific train and a farmer, Albert Bindel, who lived a few hundred yards from the accident site.

Duane Harms wasn't asked to attend because authorities had his account under oath. Only his statement represented him.

Four members of the train crew sat side by side on the front bench. Herbert F. Sommers, the engineer, wore his bib overalls, a burning cigarette in his right hand.

Brakeman George C. Campbell and conductor Raymond W. Courtney still wore their dark work suits, ties clinched at their necks, small "UP" pins on their lapels.

Fireman Melvin C. Swanson, who was sitting across the locomotive cab from Sommers when the train bashed into the bus, wore a cardigan over his white, open-collared shirt.

Sommers testified first, explaining why the train was an hour and 45 minutes late. It was "the Christmas rush," he said. The train had been even later the day before.

He described the approach of the bus.

"He slowed down," Sommers said, "apparently like he was going to stop, and got right up to the shoulder of the track and appeared like he slowed down to about 5 miles an hour and stepped on the gas and drove right in front of us."

Ahlborn asked if Sommers was certain the bus didn't stop.

"Absolutely certain," Sommers replied.

Swanson, the only other crew member to see the collision, testified next.

"Well, I seen the bus approaching the right of way there, and he slowed down," Swanson said. "I thought he was going to stop and was hoping he was going to stop, and to my surprise he went right in front of us."

Bindel testified last. The farmer said he was getting his children ready for school just before the crash.

"As I was getting them rigged out to go to school, I saw the school bus pass by, and also hearing the train coming down the track, I stepped around the corner of the house, and the bus pulled up to the railroad track, and its red lights were on and ..."

"What red lights are you talking about?" Ahlborn asked, interrupting him.

"The back part of the bus is all I saw," Bindel said, "and, as near as I saw, the bus was stopped still."

Ahlborn pressed him.

"I noticed the red light where he had stopped," Bindel said, "and I said to myself, 'Well, the bus has stopped.' "

Then he acknowledged it was possible the bus didn't come to a complete stop.

"I won't leave that word 'maybe' out," he said. "From where I was and what I could see, the bus had stopped, and I still say that's right."

Later that night, Greeley Tribune reporter Jim Hitch stopped by Weld County General Hospital. He visited the third-floor room of Jerry Hembry, the sophomore who had been sitting in the front seat of the bus, who had yelled "train!" at the last moment. The crash dislocated Jerry's shoulder and broke his collarbone, but he was positive Harms had stopped.

"The bus stopped and then started up again," Hembry said from his bed. "I looked up and saw the train's light. The next thing I knew we were hit."

'My deepest sympathies'

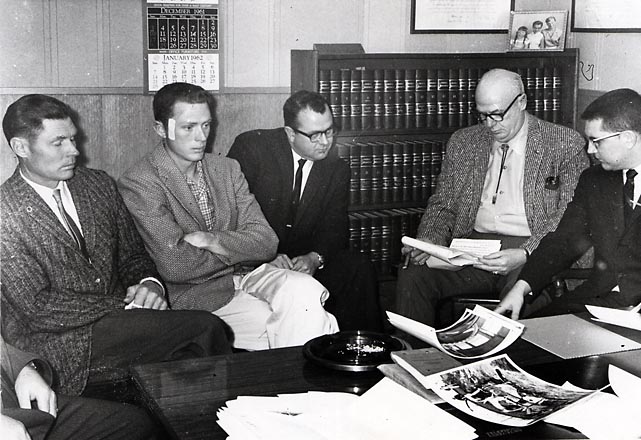

The next morning, Harms, wearing a tweed sport coat over a plaid shirt, sat in prosecutor Ahlborn's office, ashen-faced, his father next to him. Ahlborn's staff and Gilbert Carrel, chief of the Colorado State Patrol, sorted through the details. Carrel puffed on a fat cigar. Glossy photographs of the crash were spread out on Ahlborn's desk.

Ahlborn told Harms he would be charged with manslaughter. Barely 27 hours had passed since the accident. As he waited for his $1,000 bond to be posted, Harms talked briefly to a reporter.

"I sure feel really bad about it," he said. "My deepest sympathies go to them."

Harms' father, Wilber, stepped to his defense.

"He is as good a driver as anyone they could ever have," he said. "He learned to drive at 16 in a wheat field. And he was so careful during high school the other children used to make fun of him."

About 150 people from Harms' hometown of Fleming signed a letter to the people of Greeley.

He was thoughtful and kind. He never did a thing to hurt a fellow student. The community held him in highest regards and wants him to know now it stands behind him.

It was only the beginning. But in that first day after the accident, Harms was blessed with a clear-thinking advocate.

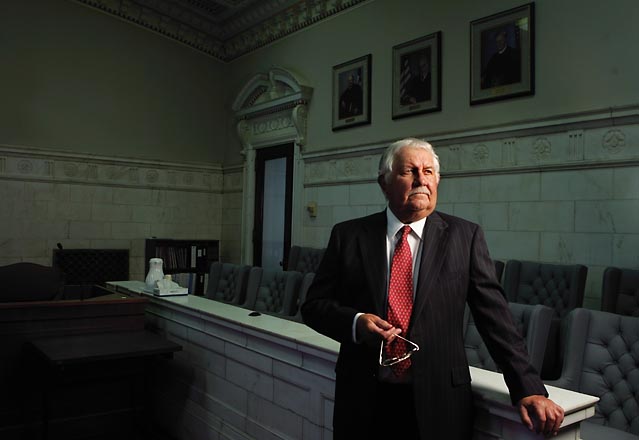

He was Jim Shelton, a well-respected Greeley lawyer appointed to represent Harms.

At 9:30 a.m. the following Monday, Shelton arose in Judge Donald Carpenter's fourth-floor courtroom and moved just as aggressively to defend Harms as Ahlborn had in pursuing charges.

"My client is still in a state of confusion, shock and anguish and cannot at this time make an intelligent decision," Shelton told the judge, who postponed the arraignment until Jan. 2.

Afterward, as Harms sat quietly holding his wife's hand, Shelton stood before a group of reporters.

"My client has bared his soul to the district attorney's office in several hours of questioning," Shelton said. "He has been a man about it, he hasn't alibied and he has been willing to accept his responsibilities."

Harms, Shelton said, suffered the "heartache and sorrow of the parents."

"He only wants to do what the parents desire. If they want to talk to him, or ask questions, he's ready," Shelton said.

Planning a defense

The trial was months away, but Shelton already knew how he'd play it. Just four days after the accident, he outlined his planned defense. It was based on a 1956 state Supreme Court decision reversing the manslaughter conviction of a Greeley bus driver who had hit and killed a 10-year-old girl.

The court ruled that to prove manslaughter, prosecutors had to show that the driver "recklessly and wantonly failed to exercise the care and caution a reasonably prudent person would have exercised under similar circumstances" and exhibited a "reckless and wanton disregard for the safety of others."

Getting up early to warm the school bus, Shelton said, "does not indicate a willful, wanton or reckless attitude for the safety and comfort of those children."

"He had a mental attitude of concern, and the matter of his mental attitude is the key to his guilt or innocence," Shelton said.

"The situation at the scene is one that was just waiting for an accident to happen. I, and the whole community, are partly responsible for what did happen. But Harms is the driver, and he'll take the consequences of his actions."

Duane and Judy Harms stepped into the hallway. Art and Juanita Larson — preparing to bury their son, Steve, and praying that their daughter, Alice, would recover — met the young couple.

"We don't hold any grudges," Art Larson told the young bus driver. "We think you're a wonderful man. We'll see to it that you get fair treatment."

NEXT: Trial