Crossing chapters

Jump to:Related content

Crossing forums

Forum at the Rocky Mountain News in Denver.

Forum at the Rocky Mountain News in Denver.

Forum at the Union Colony Civic Center in Greeley.

Forum at the Union Colony Civic Center in Greeley.

Podcasts:

Acknowledgements

"The Crossing" could only be told with the help of many people:

- The more than 80 people touched by the tragedy of Dec. 14, 1961, who agreed to tell their stories.

- Bill and Mary Bohlender, who helped unearth numerous historic documents and provided numerous insights.

- Virginia Shelton and Mary Shelton Shafer, who provided numerous insights and access to attorney Jim Shelton's files.

- Keith Blue, who provided numerous insights.

- Peggy Ford and the staff at the City of Greeley Museums, Barbara Dey and the Hart Library staff at the Colorado History Museum and former Rocky librarian Carol Kasel, who all assisted with research.

Contact the series team

- Reporter: Kevin Vaughan

- Photographer: Chris Schneider

- Video: Tim Skillern & Laressa Bachelor

- Print designer: Armando Arrieta

- Web designer: Ken Harper

- Web producer: Forrest Stewart

- Web developer: Chris Nguyen

- Copy editor: Dianne Rose

- Photo editor: Dean Krakel

- Imager: Marie Griffin

- Interactive editor: Mike Noe

- Project editor: Carol Hanner

Laughter breaks loose from Juanita Larson's throat, and a great torrent of happiness fills her living room. In her mind, she is back in 1961.

The cows have wandered away from the 23-acre farm where she lives with her truck-driver husband, Art, and their four children, Nancy, Linda, Alice and Steve.

Linda, 13, has driven off in the family car to look for the cows. Steve, not quite 10, has gone with her.

Linda returns, alone and on foot, the cows in tow.

Juanita is exasperated.

"You mean I have to go all the way down there and get that car?" she huffs.

"Oh, no," Linda answers, "Steve's bringing it."

And pretty soon, here comes the 9-year-old boy at the wheel of the maroon-and-white '48 Chevy, steering slowly along the irrigation ditch and up the dirt driveway.

"He brought it all the way home," Juanita says, her voice a rising tide of joy, "just as big as you please."

And the laughter erupts again in her Gilcrest home, not far from U.S. 85 south of Greeley.

For Juanita Larson, talking about her only son, the one she lost 45 years ago along the railroad tracks, is a pleasure.

As she reminisces, her husband of 60 years sits a few feet away, beanpole-skinny, his hands clasped loosely in his lap, thumbs fiddling.

A survivor of four strokes, he doesn't talk much, at least not on this day, but Juanita is as talkative as he is quiet.

The happy memories of Steve spill from her as if they had happened last month.

One time she was visiting down the road at a neighbor's house, while Steve played with a friend.

"He and Steve got on our horse, and they were riding it around their farm. The horse decided to go one way, and the kids went the other way," she says, the laughter coming hard.

Another time Steve sold some of his rabbits to an aunt. He beamed at the prospect of making some money.

But the smile slid off his face when his aunt handed him a check.

"He was so disappointed because he wanted money, not a piece of paper," Juanita says.

And there was the time Steve, the little instigator, talked Juanita into climbing onto a trampoline with him and his friends.

They started jumping, and Juanita, unable to find her balance, got bounced around in the middle, her knees and elbows and nose rubbed raw on the black mat.

"You start talking about it, and you start thinking about all the wonderful things, and people who don't ever have any children, they don't have any idea how wonderful it is to have children," she says.

A deal with God

Her children came quickly into her life. She and Art married in 1946, and by January 1952, they had three girls and a boy.

Then, in 1955, Juanita was diagnosed with cervical cancer.

As she fought through radiation and surgery, she offered God a deal: Heal me, and I'll bring all my children up in the church.

"I knew that my kids were not going to be raised by a stepmother," she says. "I just told him, 'I'm not ready for you.'"

God kept his end of the bargain, and she kept hers.

In 1957, Art and a healed Juanita moved onto a small farm in the Auburn area southeast of Greeley. Art drove a truck, droning up and down U.S. 85, hauling merchandise between Greeley and Denver.

Juanita worked as a nurse's aide on the night shift. They raised a few animals and some alfalfa.

They went to church.

In the fall of 1961, Steve found a new friend.

His name was Duane Harms, the school bus driver. In Harms, Steve found a kindred spirit of sorts.

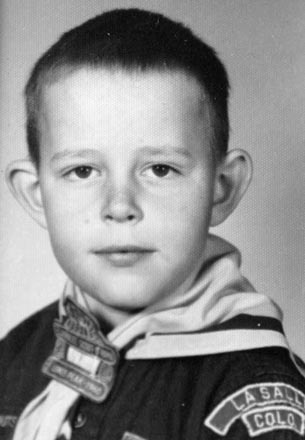

Steve was not quite 10, but he was already wearing size 12 pants, and his feet were big.

When other kids made fun of the clumsy boy, Harms pulled Steve aside.

You're growing so much that your feet and your legs, they're not keeping up with what you want to do with them, Harms told him.

When there was no one else to play with Steve at school, Harms did, racing him on the playground.

Forty-five years later, Juanita still remembers the evenings that fall when Steve spent all his time talking "about what Duane did, or what Duane and I did, or what Duane said to me."

"Duane was so good to him," Juanita says.

On Dec. 14, 1961, Linda was sick, so Juanita kept her home. Alice, who was 11, and Steve, who was a month from his 10th birthday, caught the bus. After a couple minutes, they swapped seats.

As Art drove Nancy to high school in Greeley, the City of Denver streamliner screamed past him.

He looked west and saw the school bus, with Steve and Alice on it, a little more than half a mile away.

Reassured when he saw the red brake lights on the bus, Art headed on toward town.

Juanita was home from her night shift at the hospital, getting ready for bed, when the phone call came.

She jumped back into her clothes, told Linda to stay put in case anyone called and sped to the crossing.

There, a neighbor, Joe Brantner, grabbed her, told her she needed to come with him to the hospital, that Alice was badly injured.

They rushed off.

As morning turned to afternoon, the shock of what had happened at the crossing settled in.

The bodies of the 20 dead children had been taken to the old state armory building on Eighth Avenue in Greeley.

Confusion wracked the families of the 36 children on the bus.

Some parents wandered the hospital's hallways, looking for their children, unable to find them. Others huddled in the freezing cold outside the armory, hoping for some word.

Still others sat in a courtroom, where grim-faced clerks took notes as investigators asked a series of questions.

How tall is your son? What color is his hair? Does he have any scars?

What was your daughter wearing when she left the house this morning? How much does she weigh?

Keeping vigil

At the hospital, Art, who had been ready to head out in his delivery truck when his boss told him about the crash, stood by Juanita's side.

They didn't know what to feel. They were unsure whether Alice would survive, unsure whether Steve was alive or dead.

Art held Alice, while Juanita helped prop up her feet and hand-pumped lifesaving saline and blood into her body.

For a time, Alice's life hung precariously.

Her liver torn, her gallbladder crushed, her appendix damaged, she was wheeled into an operating room.

Art and Juanita both hoped that Steve was all right somewhere, maybe knocked out, maybe getting treated in another part of the hospital.

Then, early in the afternoon, they learned the worst. Steve had been found dead in a ditch along the tracks.

Alice came out of surgery alive, but she was still in bad shape.

A doctor pulled Juanita aside. Alice's stability was so fragile, he told her, that finding out her little brother was dead could send her into a deep shock and kill her.

So they kept the news from Alice for three weeks, as she slowly regained her strength.

While she was in the hospital, they buried Steve in his blue Cub Scout uniform with the yellow neckerchief.

NEXT: Questions