Crossing chapters

Jump to:Related content

Crossing forums

Forum at the Rocky Mountain News in Denver.

Forum at the Rocky Mountain News in Denver.

Forum at the Union Colony Civic Center in Greeley.

Forum at the Union Colony Civic Center in Greeley.

Podcasts:

Acknowledgements

"The Crossing" could only be told with the help of many people:

- The more than 80 people touched by the tragedy of Dec. 14, 1961, who agreed to tell their stories.

- Bill and Mary Bohlender, who helped unearth numerous historic documents and provided numerous insights.

- Virginia Shelton and Mary Shelton Shafer, who provided numerous insights and access to attorney Jim Shelton's files.

- Keith Blue, who provided numerous insights.

- Peggy Ford and the staff at the City of Greeley Museums, Barbara Dey and the Hart Library staff at the Colorado History Museum and former Rocky librarian Carol Kasel, who all assisted with research.

Contact the series team

- Reporter: Kevin Vaughan

- Photographer: Chris Schneider

- Video: Tim Skillern & Laressa Bachelor

- Print designer: Armando Arrieta

- Web designer: Ken Harper

- Web producer: Forrest Stewart

- Web developer: Chris Nguyen

- Copy editor: Dianne Rose

- Photo editor: Dean Krakel

- Imager: Marie Griffin

- Interactive editor: Mike Noe

- Project editor: Carol Hanner

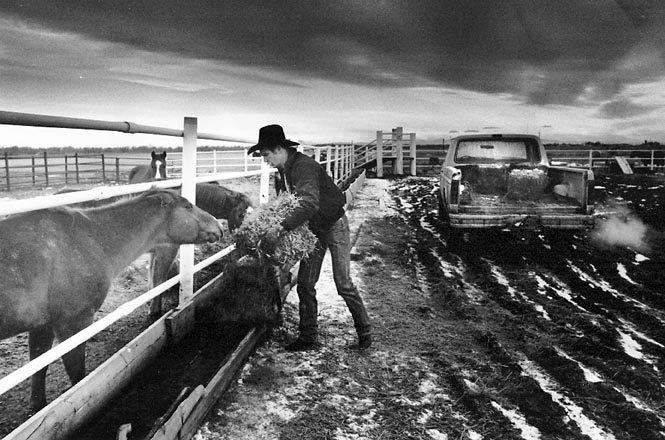

A wiry whip of a man steps onto an old overturned bucket, throws his right leg over the back of a chestnut horse and pushes and pulls his way on.

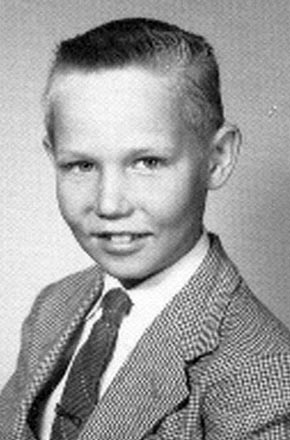

The horse isn't saddled, but that's no problem. Nor does it matter that the man is 54 years old, and has diabetes, and has just knocked out his front teeth, again. Bruce Ford's been rambunctious all his life, and he's rambunctious still.

He's ready to do a little business. A man has pulled into the yard in front of his ranch northeast of Kersey, looking to buy two horses.

Bruce rides one horse around a small pen on a postcard-perfect afternoon, puffy clouds hanging overhead, sunshine bouncing off his craggy face.

A minute later, he slides off the horse, pries open the animal's mouth and shows the man its teeth. They talk price.

There's an offer and a counteroffer, then a third horse enters the deal.

After some more bartering, they agree on a price, shake hands. Bruce leads two of the horses out of the pen and toward a long white trailer. He chuckles.

"A day at the 9-to-5," he says.

A boy remembered

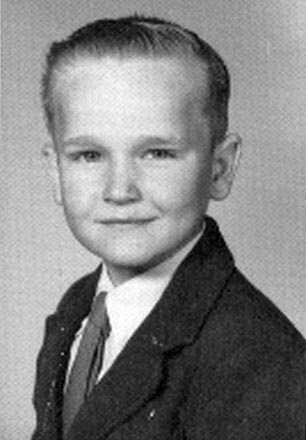

Glen Ford plops in a comfortable chair in the living room of his mother's home near Kersey, just a few yards from Bruce's house.

He rests his left hand up against his face, sets his blue baseball cap on his right knee.

Bruce rocks back and forth a few feet away. His well-worn jeans are tucked into a dusty pair of boots, silver spurs sticking out above the heels. His handlebar mustache curls into twin silver-dollar-size hoops below his wire-frame glasses.

The two cut up, bust each other's chops, chuckle now and then. They laugh at the stories about their big brother, Jimmy.

He was two years older than Glen, four years older than Bruce. If there was one thing he loved even more than his horse, it was playing baseball. He played so much, and for so long, that he'd wear out his brothers. And it was dangerous to try to quit before Jimmy was ready.

If you wanted to stop, you'd better give him a fat pitch that he could hit a long way so you could make it to the house.

"If you went to the house before, he'd hit you with a ball, or he'd throw the bat and hit you with it," Glen says. "I mean, you had to make sure that he was far enough away from all that junk so that you could gas to the house.

"You'd better keep running."

That was just the way it was with the three sons of Jim Ford, a bricklayer and cowboy, and his curly-haired wife, Loretta.

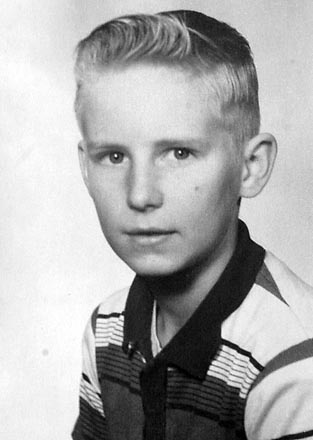

They named their first son James Vaughn Ford after his father and Loretta's brother, Chester Vaughn Morey, an infantryman who died in Italy in World War II.

When their second son came along, they called him Glen Elmeron Ford, his middle name coming from his grandfather. And when Loretta was pregnant for the third time, she knew — just knew — it would be a girl, and that she'd call her Mary Colleen.

Jimmy and Glen, 4 and 2, had other ideas. They loved going to the stock-car races, loved rooting for their favorite driver, Bruce Ruth.

We're going to call our little brother Bruce, they'd tell their mother.

When Loretta gave birth, it was a boy, and she and Jim named him Bruce Eugene Ford.

Loretta laughs at the story. She is a kindly woman who tilts her head slightly and smiles when she talks about her family.

Her voice shakes a little, perhaps the result of a small stroke. But her mind is sharp, and her memory of her three hell-bent-for-leather boys is keen.

Whatever they were doing, they knew only one way: all out.

They charged for the house on their horses — exactly what they weren't supposed to do.

They ran through the sagebrush, barefoot half the time, BB guns in their hands. They dashed into the house at day's end and tossed their pants right there, a lizard squirming free and scampering across the floor. They swam in the irrigation ditch in the summer, ice-skated on the pond in the winter.

Losing Jimmy

On Dec. 14, 1961, the three Ford brothers bounded onto their school bus, in such a hurry they didn't kneel in prayer with their mother as they did most mornings.

A minute later, Jim headed to town with Loretta to take her to her housecleaning job. They came to the crossing, saw the front of a school bus in a heap on its side, saw the last few feet torn away.

They found 13-year-old Jimmy, by the tracks, dead.

They came upon 9-year-old Bruce, crumpled on the ground, a trickle of blood leaking from his ears and nose.

He looked dead. Loretta bent down, called his name. Bruce moaned quietly. His right arm, collarbone and some ribs were broken.

He would remain unconscious for five days with a head injury.

Just then, 11-year-old Glen and another boy stumbled out of the hulk of the bus. The collision had knocked out Glen's front teeth, rubbed great hunks of skin off his face, gashed his forehead, slashed his leg. Cinders clouded his eyes, leaving him temporarily blind. Still, he was in pretty good shape.

The boys were both home by Christmas. New saddles waited under the tree on Christmas morning.

They missed their brother, but they were still boys. They stuck close together, as they always had.

They rode their horses, Prince Tiny and Pepino. They romped through the fields. They skated and swam.

They still played baseball, but it wasn't the same without Jimmy.

In 1964, Jim and Loretta sold their 160-acre farm — the one that had belonged to his father — and headed to Oregon. Jim could work year-round there, bricking fireplaces in the mild climate. But six months later, they packed up and returned to Colorado.

They tried Oregon twice more before coming back home for good in January 1970.

Amid all the change, several constants remained in their lives. They loved each other. They believed in God. They understood, as Bruce puts it now, that death is a part of life.

And, always, they rode horses.

Rodeo kings

By the late 1960s, Glen and Bruce had both tasted rodeo, both felt the surge of adrenaline when they would "get on" in an arena filled with a raucous crowd.

Glen earned his professional card eight seconds at a time, hanging onto the back of a snorting, slobbering 1,500-pound bull with only one thing on its mind — throwing him off. Later, he rode bucking horses, bareback, and he was pretty good at that, too.

His best year was 1976, when he finished 12th in the world in bareback riding and made it to the National Finals, the Super Bowl of rodeos. Only the top 15 in the world in each event get invited.

The rodeo life provided Glen a decent living.

In 1980, he bought back 35 acres of his parents' original farm, where he and his wife, Jane, raised their three sons.

Bruce found his place in rodeo, too — despite a doctor's warning to avoid anything that could lead to a knock on the head, despite his father's insistence that he wear an old plastic football helmet before he climbed onto a horse.

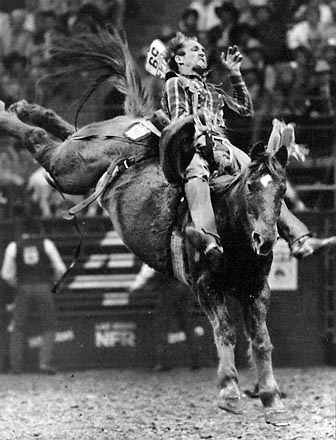

Bareback was Bruce's joy. While Glen found success and happiness in the arena — and made enough money to pay off his farm by the time he was 40 — Bruce found something else. Stardom.

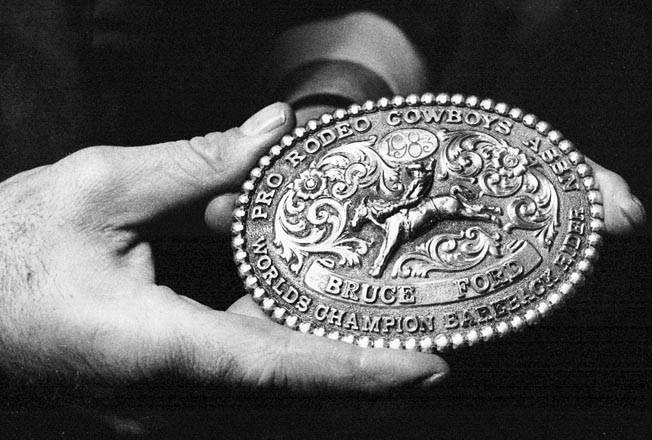

Before he was done, he was a five-time world champion. A 19-time qualifier for the National Finals Rodeo. The first rodeo cowboy to win $100,000 in a year and one of the first to take home $1 million in a career.

Bruce gave it up in 2000, settling down on the ranch where he and his wife, Susie, brought up their kids. Horses remain his life's work, in the rodeo schools he has operated for more than 30 years and in the horse-trading business he runs.

"It's the same reward I got from rodeoing," he says of horse trading. "You sell one good and it's just like winning the day money. You buy an old bum, it's like kickin' over the neck, I guess, and getting bucked off."

Glen got out earlier, in 1991. But, as with his little brother, don't think he doesn't still get on. He'll break a colt once in a while.

As Glen talks about walking away, a twinge of regret creeps in.

"If I had it to do all over again," he says, "I'd do it just a little harder."

But by the time he ambled out of the rodeo arena for good, he'd found something else he enjoyed.

It had happened in 1984. His wife, Jane, called him one day, told him the school district where she worked needed someone. Glen went down, filled out the paperwork. Then he started a job that took him closer to the crossing than he could ever have imagined.

NEXT: Memories