Click and drag image

Crossing chapters

Jump to:Related content

Crossing forums

Forum at the Rocky Mountain News in Denver.

Forum at the Rocky Mountain News in Denver.

Forum at the Union Colony Civic Center in Greeley.

Forum at the Union Colony Civic Center in Greeley.

Podcasts:

Acknowledgements

"The Crossing" could only be told with the help of many people:

- The more than 80 people touched by the tragedy of Dec. 14, 1961, who agreed to tell their stories.

- Bill and Mary Bohlender, who helped unearth numerous historic documents and provided numerous insights.

- Virginia Shelton and Mary Shelton Shafer, who provided numerous insights and access to attorney Jim Shelton's files.

- Keith Blue, who provided numerous insights.

- Peggy Ford and the staff at the City of Greeley Museums, Barbara Dey and the Hart Library staff at the Colorado History Museum and former Rocky librarian Carol Kasel, who all assisted with research.

Contact the series team

- Reporter: Kevin Vaughan

- Photographer: Chris Schneider

- Video: Tim Skillern & Laressa Bachelor

- Print designer: Armando Arrieta

- Web designer: Ken Harper

- Web producer: Forrest Stewart

- Web developer: Chris Nguyen

- Copy editor: Dianne Rose

- Photo editor: Dean Krakel

- Imager: Marie Griffin

- Interactive editor: Mike Noe

- Project editor: Carol Hanner

In the beginning, Aleta Craven could not look at the stories. All she could do was print them out on her computer and slip them into a desk drawer.

She and her family had seldom talked about Dec. 14, 1961, the day two of her children and 18 others died when a train hit their school bus near Greeley.

For the Cravens, the silence that had surrounded the tragedy persisted. So did the pain.

But over the past six weeks, as "The Crossing" series unfolded, something broke loose.

In their home in Gill, the Cravens started talking about things they'd never talked about before.

They weren't alone. Doors began to open in others' lives, too.

In Southern California, the school bus driver, Duane Harms, received a small package and a letter from the sister of a boy who had died in the crash. And Duane responded, reaching through the wall that stood between him and those who lost children.

In Greeley, Alice Larson Richardson, whose childhood was wrapped in silence about the death of her brother, stood up in front of nearly 700 people and spoke, eloquently, about her experience.

"I, like so many others, never talked about this accident," she said. "Now people are asking questions, and even praying for us."

Insight

Aleta Craven and her husband, Ralph, never knew what their youngest son, Mike, went through. They never knew he'd been driven out to the scene of the crash, had seen where his older brother and sister died. They never knew that a relative had told him to never talk about the family's loss.

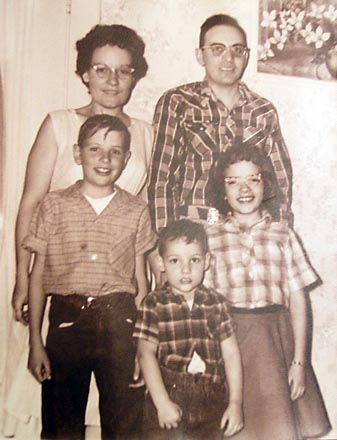

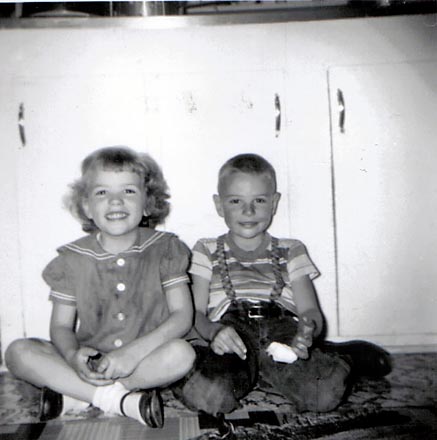

Calvin Craven was celebrating his 10th birthday on Dec. 14, 1961. That morning, he and his 8-year-old sister, Ellen, climbed onto the school bus. Barely 10 minutes later, they were both dead.

Over 45 years, it was hard to find the words to make sense of it. For Aleta and Ralph. For Mike, who was 4 1/2 years old when Calvin and Ellen died. Even for their daughter, Susan, adopted nearly three years after the accident.

Last fall, they decided they did not want to be interviewed for the series. Talking about their loss was too hard.

When Aleta started seeing the stories, she was upset.

One day, Mike started talking — really talking — about losing Calvin and Ellen, about the hole in all of their hearts that will never completely heal.

He told his parents the things they never knew, told them how he'd carried his grief through his life.

Susan started talking, too. She'd always been caught in an awkward place, trying to understand a brother and sister she never met.

"When I would tell people about this, I would say, 'My mother and father's older kids,' not my 'brother and sister,'" she said.

She's talked to her mother about it. Now she knows she can call Calvin and Ellen whatever she's comfortable with.

Even Ralph started talking more.

"This has been so good for us," Aleta said.

Discovery

For as long as she could remember, Debbie Stromberger Keiser did not know who had saved her life.

She was 7 on Dec. 14, 1961, and she was the only child in the very back of the bus to survive. She knew that a couple had stopped to pray over her, thinking she was dead. She knew they had realized she was alive, gathered her up and raced her to the hospital.

Then, in late January, she saw a message on RockyMountainNews.com posted by Daryl Neukirch of Waxahachie, Texas. His late parents, George and Evelyn Neukirch, had grabbed Debbie that day, had sped to the hospital, had struggled to keep her from swallowing her tongue.

Debbie hesitated for a time. Then she left a phone message for Daryl. He called back a few minutes later. The conversation was emotional, for both of them.

"I don't know how to say 'thank you' enough to them," Debbie said.

Connections

A UPS truck pulled up outside the home of Duane Harms in January, bringing him a small cardboard box.

Inside, he found a letter from Carolyn Baxter Tucker and a package of exotic rocks she had collected over the years. Carolyn's little brother, Jerry Baxter, had died on the bus.

Carolyn wanted Duane to know she believed the accident was God's will. She wanted him to know that they shared an interest in beautiful, interesting stones.

Duane wrote a letter of his own. Then he picked out some rocks from his collection, boxed them all up and mailed the package to Carolyn. It was his first contact with any of the families since he left Colorado in 1962.

Gratitude

On Feb. 15, Jerry Hembry's story appeared.

The oldest boy on the bus, he'd been seriously injured, then led several younger children to a farmhouse to find help.

One of those children was Smith Freeman.

Smith read the article about Jerry. He went to a message board where hundreds of people have posted thoughts on "The Crossing."

He started typing.

Jerry I have to take this opportunity to say Thank You. I was only 7 years old and remember that I was going to just walk home that day and you took my sister, Joy, myself and one of the Munson boys to a nearby house to be taken care of. I always wanted to say Thank You to you for that. ...

I remember as a young boy my parents took me to East Memorial School when it was completed to see the plaque on the column that had the names of the victims, including my sister, Melody. I believe it should also have mentioned the heroes, like you.

Support

Alice Larson Richardson stepped to the microphone last month at a community forum in Greeley. In front of her sat nearly 700 people.

For much of her life, she hadn't talked about surviving the crash, about losing her brother, Steven, after the two of them swapped seats.

Now she was explaining her decision to tell her story in the series and recounting the ways it affected her.

It had, she said, answered many questions.

"It's also opened up doors," she said, "allowing me to talk about the accident, to hear about the others who had been on the bus with me that day, and to start healing after so long."

A moment later, Mike Craven stood, and nearly 700 people joined him, and they showered Alice with appreciation in a standing ovation.

Remembrance

Tim Geisick always wondered why the place where the train hit the bus bore no memorial to the 20 children who died.

Dec. 14, 1961, had touched his family on both sides. His dad's cousin, Randy Geisick, was injured. His mother's brother and sister, Mark and Kathy Brantner, died.

He decided to do something about it. He obtained permission to place a marker on land next to the tracks, not far from the accident site. And he opened a bank account and began raising money. He's close to the $6,500 he needs for the monument.

Healing

Last week, Aleta Craven drove along County Road 52. She stopped a quarter mile east of County Road 43, very close to the place where Calvin and Ellen and 18 other children died.

She hadn't been there since Dec. 14, 1961.

A couple months after that awful day, she and Ralph sold their one-acre place in the Auburn community and moved into Greeley.

Mike would go to kindergarten the next fall, and they could not imagine putting him on a school bus.

Over the years, she had never wanted to go to the place where the children died. But there she was, sitting at the side of the road, thinking, remembering. A few days later, she took Susan and went again.

Being there was terribly hard, but, in an unexpected way, good.

It was there, for the first time, that she felt a permanent memorial was right.

Later this year, if all goes as planned, a simple granite spire will forever mark that spot.

NEXT: Extras