Crossing chapters

Jump to:Related content

Crossing forums

Forum at the Rocky Mountain News in Denver.

Forum at the Rocky Mountain News in Denver.

Forum at the Union Colony Civic Center in Greeley.

Forum at the Union Colony Civic Center in Greeley.

Podcasts:

Acknowledgements

"The Crossing" could only be told with the help of many people:

- The more than 80 people touched by the tragedy of Dec. 14, 1961, who agreed to tell their stories.

- Bill and Mary Bohlender, who helped unearth numerous historic documents and provided numerous insights.

- Virginia Shelton and Mary Shelton Shafer, who provided numerous insights and access to attorney Jim Shelton's files.

- Keith Blue, who provided numerous insights.

- Peggy Ford and the staff at the City of Greeley Museums, Barbara Dey and the Hart Library staff at the Colorado History Museum and former Rocky librarian Carol Kasel, who all assisted with research.

Contact the series team

- Reporter: Kevin Vaughan

- Photographer: Chris Schneider

- Video: Tim Skillern & Laressa Bachelor

- Print designer: Armando Arrieta

- Web designer: Ken Harper

- Web producer: Forrest Stewart

- Web developer: Chris Nguyen

- Copy editor: Dianne Rose

- Photo editor: Dean Krakel

- Imager: Marie Griffin

- Interactive editor: Mike Noe

- Project editor: Carol Hanner

Duane Harms decides he wants to write something to sum up his thoughts about that fatal day he drove his school bus onto the crossing.

Something about the 45 years that have since passed. Something that will answer the questions that never go away.

It's a warm evening in Southern California.

He gets out a pencil and a yellow notepad with a blue cover.

He prints very neatly.

I was hoping against hope that the bus accident would not be brought up before the public attention. For the most part I wish that it not be done. It's sad that most news on T.V. and newspapers is not good.

Right after the accident I was in such shock and sadden that I didn't really know what to do. The family and friends had to go through great sorrow and were very burdened, it was a very sad time. I'm really sorry. I just wish that I had offered more condolences, sympathy, thoughts and prayers to all.

He starts another paragraph, repeating the sentiment he expressed in 1961, one that fostered respect from many people.

I would have been willing to have died in order that one or all could have lived. I would also have been willing to do jail time.

He is halfway down the page now.

The children were all real good kids. Sometimes at recess when I was at Delta School, I'd join them in playing ball.

I appreciate all the people that helped in the time of need. Thank you. It's good to hear that some of the people that I knew back then are now successful and doing well.

Things happen that seem to be unfair. I believe that there is a almighty Lord God up above that all of us can turn to.

Only four more blank lines remain. He writes two more sentences.

People may wonder how I'm doing now. I'm OK.

Duane

Staying close

The back door swings open and slams shut.

Children rush in and out. In the corner, a video game squawks.

It is "Third Sunday" at the home of Alice Larson Richardson and her husband, Ron.

Their four grown daughters, Kynda and Rhonda and Tawnya and Melissa, are here.

So are their sons-in-law and their 10 grandchildren.

Alice and Ron began the ritual 10 or 11 years ago, as their children married and had children, and schedules got crazy and getting everyone together got tougher.

So they picked a day, the third Sunday of every month, when none of them would schedule anything else, so they could enjoy a meal and each other.

"Too many people lose touch with their kids after they get married," Alice says in a moment of quiet amid the din of a house full of people.

"And they don't know their grandkids all that well."

For Alice, this gathering is partly a legacy of the accident of Dec. 14, 1961, that took her little brother, Steve.

She knows that every day with the people she loves is a gift.

Part of it is an effort to recapture Sundays at her grandmother's house, where she and her cousins played outside while the grown-ups sat for hours around the dining room table, eating, telling stories, laughing.

By 3 o'clock on this afternoon, empty plates and leftover pizza and lasagna cover the table. The kids are outside playing.

Kynda, a nurse, has gone home to get some sleep before her night shift at the hospital.

Alice sits at the dining-room table, with Melissa and her husband, Taran; with Tawnya and her husband, Landon; with Rhonda and her husband, Paul.

Alice's husband, a police officer in nearby Kersey, is headed to work. He gives Melissa a quick kiss.

"Bye, Daddy," she says.

"Love you," Ron answers.

As he crosses the room, Melissa says, "Daddy, Taran wants his hug and kiss."

Ron spins around and stops just short of kissing his son-in-law, too. Laughter ricochets off the dining room walls.

Fragments

Bob Brantner searches his mind, sees snippets of Dec. 14, 1961.

His big green farmhouse teeming with people. His school bus cut in two pieces. Later, the little brass crosses clinging to the caskets that hold his brother and sister.

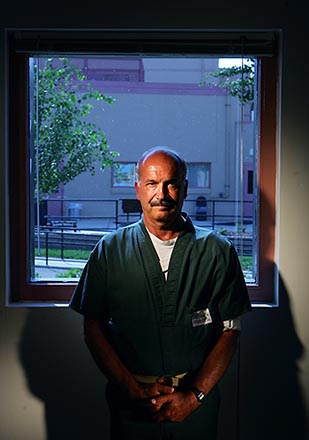

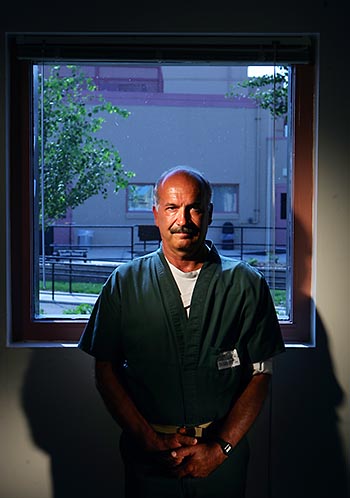

But he is not fixated on Dec. 14, 1961. Nor on Dec. 14, 1992, the day his wife was found dead, the reason he is in prison.

Instead, he tries to keep busy. He walks in the prison yard, writes letters, studies the law.

He has an appeal pending that he hopes could mean a reduced sentence and, perhaps, a chance to take care of his ailing mother in Greeley. And he teaches, helping inmates get their general equivalency diplomas.

On a bright afternoon, on the second floor of the administrative building at the Four Mile Correctional Center near Cañon City, he looks out a big window.

Past the tall fence and sharp wire, past the parking lot, he points to the white cinderblock barn and cattle pens of a dairy that supplies prisons and schools with milk.

"It goes from there," he says, pointing to the last row of fences to the east, "all the way up to there," pointing to a road to the west.

"Over there, you've got your heifers and calves," he says.

"There, you've got your dairy cows.

"It's about 1,800 head."

For a moment, he is not inmate No. 83609, waiting for the state appeals court to consider his latest motion, waiting for September 2009, the first time he could be considered for parole.

For a moment, he's got the smell of feed and manure in his nostrils, the feel of the farm in his veins. For a moment, he is home.

Familiar scene

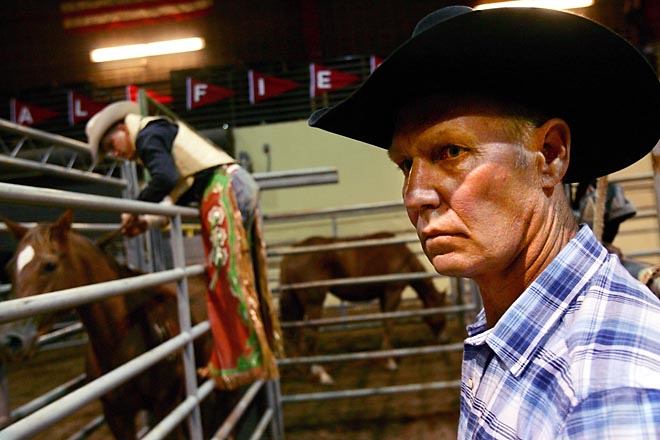

On a Saturday afternoon, Heath, Nic and Jarrod Ford and a bunch of their friends head out into the pasture.

They're home, taking a break from the rodeo circuit that keeps them on the road hundreds of nights a year. They're on the same farm where their fathers, Glen and Bruce Ford, grew up.

Where their Uncle Jimmy lived until his death on Dec. 14, 1961.

They're doing the same thing that the earlier generation of Ford boys did.

They're playing ball. It's nothing fancy. Bricks for bases. Worked-over bats. Someone wears a very old five-finger fielder's glove with the name Jimmy Ford printed in the leather on the thumb. About the only thing that's new is the ball.

They play for hours, just like their dad and their uncles did.

Though none of them knew their Uncle Jimmy — he died 16 years before the oldest, Heath, was even born — they feel close to him in some way that's hard to explain.

They grew up with the stories about Jimmy.

They know about his antics, about the stuff he'd throw at his brothers if they tried to quit a baseball game before he was ready.

Over the years, they've played ball and thought about him.

The day after this game, Heath decides to drive up to Linn Grove Cemetery to pay his respects to his grandfather and his uncle.

He walks up to Jimmy's grave, a new baseball in his hand, scuffed in a few places from the game the day before.

He sets the ball down on Jimmy's headstone, the one with the horse and the Bible chiseled into it.

He walks away.

In memoriam

In the first week of April 1963, a road crew went to work with bulldozers and graders out near the crossing.

First, they cut a new road along the south side of the tracks, on farmland that once belonged to the Brantner family.

Then they ripped out the old crossing.

Where the old road had approached the tracks at a sharp angle, they pounded seven metal fence posts into the ground, strung barbed wire across them and hung up a "road closed" sign.

When they were done, the crossing was gone.

Later that fall, a new elementary school opened on East 20th Street, a few blocks from the Delta school where the bus was going on that snowy Thursday morning.

Weld County School District 6 officials were determined to pay tribute to the 20 children who died.

They called it East Memorial Elementary School. They hung a simple bronze memorial in the main hallway.

They dedicated the school on Feb. 9, 1964, with a string quartet from Meeker Junior High performing Bach and the families of 14 of the dead children on hand.

That school, and that plaque, and a red leaf maple tree planted outside remain the only permanent public memorials to the children.

Out at the crossing, a brown and brittle wreath, left in December on the 45th anniversary of the accident, dangles from a fence post, near a couple of sprays of flowers and two poems.

Nothing else marks the spot.

NEXT: Epilogue

This story orginally gave the incorrect time span between the bus crash and the birth of Heath Ford.