Crossing chapters

Jump to:Video

Children board the school bus, choosing seats that could determine whether they live or die.

Watch video

Watch video

Related content

Crossing forums

Forum at the Rocky Mountain News in Denver.

Forum at the Rocky Mountain News in Denver.

Forum at the Union Colony Civic Center in Greeley.

Forum at the Union Colony Civic Center in Greeley.

Podcasts:

Acknowledgements

"The Crossing" could only be told with the help of many people:

- The more than 80 people touched by the tragedy of Dec. 14, 1961, who agreed to tell their stories.

- Bill and Mary Bohlender, who helped unearth numerous historic documents and provided numerous insights.

- Virginia Shelton and Mary Shelton Shafer, who provided numerous insights and access to attorney Jim Shelton's files.

- Keith Blue, who provided numerous insights.

- Peggy Ford and the staff at the City of Greeley Museums, Barbara Dey and the Hart Library staff at the Colorado History Museum and former Rocky librarian Carol Kasel, who all assisted with research.

Contact the series team

- Reporter: Kevin Vaughan

- Photographer: Chris Schneider

- Video: Tim Skillern & Laressa Bachelor

- Print designer: Armando Arrieta

- Web designer: Ken Harper

- Web producer: Forrest Stewart

- Web developer: Chris Nguyen

- Copy editor: Dianne Rose

- Photo editor: Dean Krakel

- Imager: Marie Griffin

- Interactive editor: Mike Noe

- Project editor: Carol Hanner

The school bus sat at the railroad tracks. Driver Duane Harms looked one way, then the other. It was about 7:45 a.m. on Dec. 14, 1961.

No train in sight, he lifted his left foot from the clutch pedal, gave the bus some gas and started across the tracks.

He had 17 children aboard, and many more to pick up.

Harms, a tall, thin 23-year-old with a wife and a new baby, had been driving a school bus for less than four months. In that time, he had never seen a train on his morning rounds as he negotiated a maze of roads in the farm country southeast of Greeley.

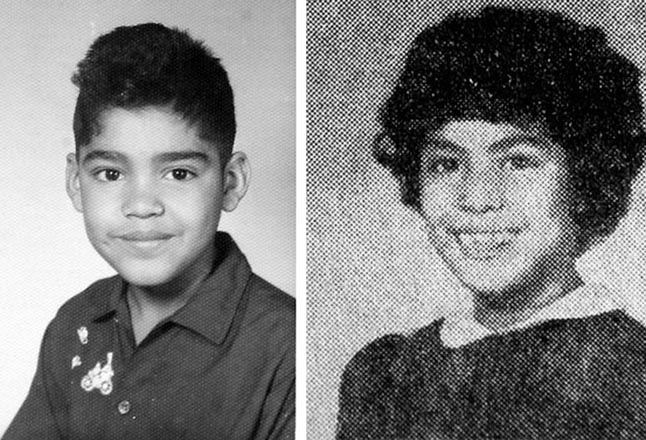

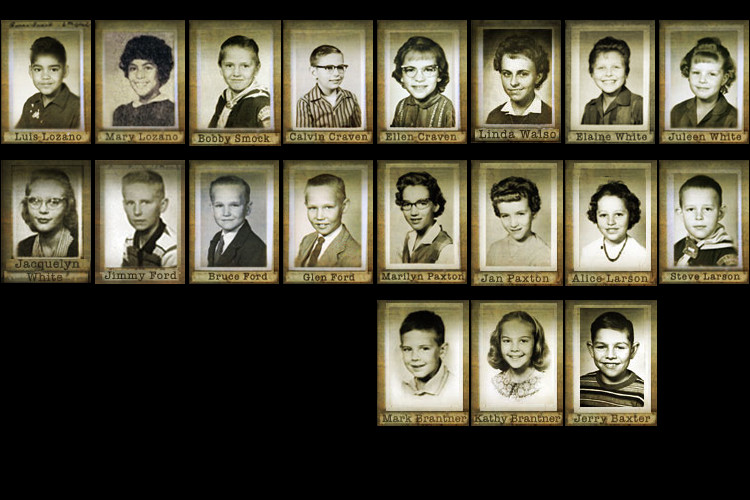

Just beyond the tracks, he stopped outside a small home close to the road to wait for Mary Lozano, 10, and her brother, Luis, 9. The children of farm workers, they had been in the Greeley area only a couple of years. Both had birthdays coming up — Luis on Dec. 23 and Mary on Christmas Day.

Mary rushed around, trying to find her purse. She called out to Luis as he headed out the door: "Tell him to wait for me."

"I'm not going to tell him nothing," Luis said.

Luis climbed onto the bus and took his seat. By then, Mary was out the door and rushing to join him.

She made it.

Harms drove on.

He watched as the Craven children — 8-year-old Ellen and her brother Calvin — got on. It was Calvin's 10th birthday.

Bobby Smock, 10, boarded at the same stop. Harms turned the bus around in the big circle drive behind the Smock home and headed back the way he had come to complete his loop.

The voices of children reverberated inside the bus as it crunched along the gravel roads.

Just around a corner, Harms met children from three families.

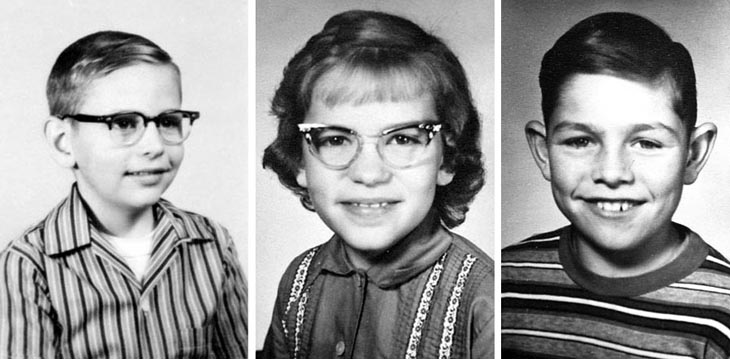

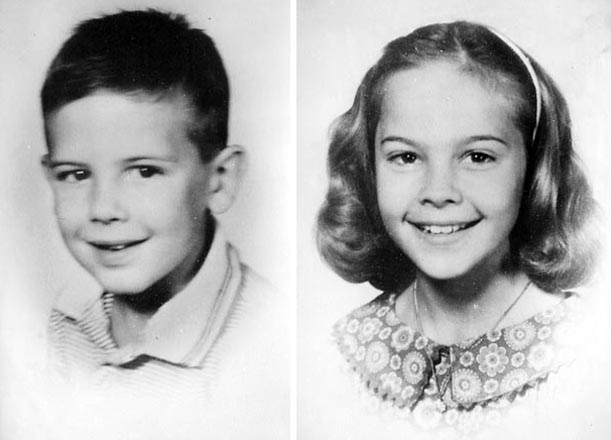

Square-jawed Jimmy Ford, 13, hopped on with his two brothers, 11-year-old Glen and 9-year-old Bruce. Jimmy moved to the back of the bus.

Glen grabbed the seat next to Alan Stromberger. Bruce jumped in near Calvin Craven and Bobby Smock, close to the back tires.

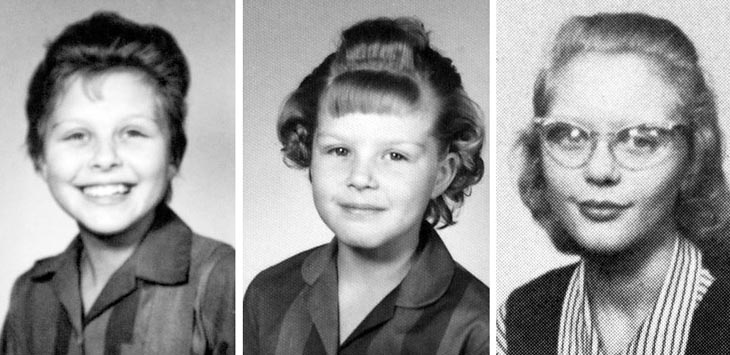

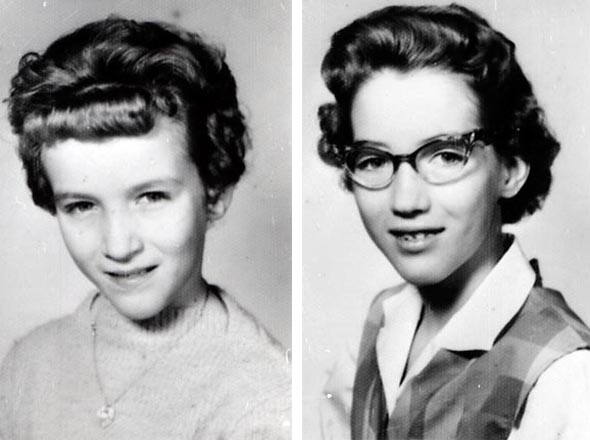

Jacquelyn White, 14, got on with her younger sisters, 11-year-old Elaine and 8-year-old Juleen.

Linda Walso, 13, whose mother led the "Auburnettes" 4-H club, headed for her usual seat in the back. Her best friend, Colleen Yetter, wasn't there. She had overslept and missed the bus.

In the next quarter mile, Harms stopped twice more, first for Jan Paxton, 11, and her sister, Marilyn, 13, two girls who loved to dance and have their pictures taken.

At the Larson home, 13-year-old Linda stayed home with a cold, but Steve and Alice bounded out the door and ran for the bus.

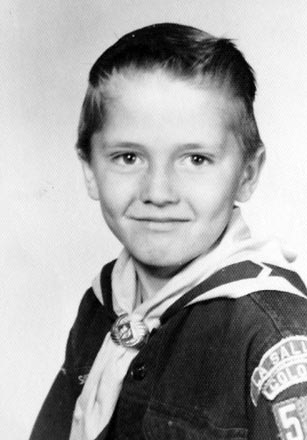

Steve, a 9-year-old whose mother led his Cub Scout den, sat toward the front; Alice, 11, headed to the back.

It was a typical morning, but a cold one. Children talked. Luis Lozano leaned over the seat in front of him and watched as two girls colored in a book. On the page was a girl in an Asian dress.

Jerry Hembry, 16, sat alone up front, his feelings hurt because none of the other kids had stopped to play cards with him.

As the bus groaned on, the Union Pacific's 16-car City of Denver passenger train, an hour and 45 minutes behind schedule, approached Kersey, six miles away.

Harms stopped next at the big, green farmhouse of Joe and Katherine Brantner and their eight children: Susie, 18; Johnny, 16; Jimmy, 14; Bobby, 12; Kathy, 9; Mark, 6; Paul, 20 months; and Mary, 2 months. The Brantners, active in the Catholic Church, farmed 320 acres, and mornings were hectic as Joe and his older boys rushed to finish milking the cows.

Johnny had his own car, and he usually drove to school and took Jimmy with him.

Three other Brantner children — Bobby, Kathy and Mark — normally rode the bus, but Bobby was already gone. He'd caught a ride with his older brother so he could talk to a teacher about a school project before class.

Mark and Kathy got on the bus.

Swapping seats

While the bus was stopped, Alice Larson moved from the back of the bus to the front, next to Mary Lozano. Kathy Brantner slid in next to them.

Kathy pulled open a Christmas book, and the three girls spread it out on Alice's lap and began looking at it.

At the same time, Steve Larson stood up from his seat near the front and went back, sitting near Bobby Smock, Calvin Craven and Bruce Ford.

It was a minor thing, really — changing seats. Yet it would be the difference between life and death.

As Harms pulled away from the Brantner farm, the City of Denver streamliner hammered along at 80 mph, just a few miles away.

Down from the Brantners, Harms stopped for Jerry Baxter, 10. A cousin of the Craven children, Jerry lived in a small home right next to the road.

The bus was 900 feet from the second railroad crossing on Harms' morning route.

Harms pulled away, heading west toward the crossing. There the road and the tracks intersected at an extreme angle — less than 30 degrees, sharper than the angle on a slice of pie. A driver going west had to twist around and look back over his right shoulder, down a thicket of utility poles, to see whether a train was approaching from the east.

There were no flashing lights or automatic arms — just a yellow "RR" sign 324 feet east of the intersection and a solitary railroad "crossbuck" sign 72 feet west of it.

Art Larson, on his way to Greeley, approached the first set of railroad tracks that Harms had crossed 15 minutes earlier. The City of Denver roared past. Larson stopped his Chevy delivery truck.

He looked to the west. He could see the bus three-quarters of a mile away, carrying two of his children, Alice and Steve.

He could see the bus stopped, could see its brake lights. He drove across the tracks and headed toward town.

At that same moment, farmer Albert Bindel was outside his home a few hundred yards from the crossing, preparing to drive three of his children to St. Peter's Catholic School in Greeley. He had seen the bus go by a minute before. Now he heard an approaching train's screeching whistle, growing louder by the moment.

He stepped out into his yard and glanced to the west. He saw the bus down at the crossing, back a bit from the tracks, red lights glowing on its rear end.

"Well, the bus has stopped," Bindel said to himself before heading inside to round up his children for the drive to school.

Frosted windows

Harms looked back over the heads of his young passengers. Although a layer of frost covered the windows along the sides and back of the bus, a slim space — about 2 inches at the top of each window — was clear.

Kids yammered. The engine idled. The motors of the heater and defroster whirred monotonously.

Harms grabbed the big steel handle to his right, pulled it toward him. The door folded open.

He looked out as best he could, trying to see over his shoulder down the tracks, peering through the utility poles jutting up along the rail line.

Harms didn't see anything. He didn't hear anything.

The temperature lingered at 6 degrees. The sun sat low in the eastern sky.

A haze hung in the air, but visibility was good.

On the bus were Harms and 36 students — 15 boys and 21 girls — bound for Delta and Arlington elementary schools, for Meeker Junior High, for Greeley High. Among them were 11 sets of siblings and two sets of cousins.

Mark Brantner, barely 6, was the youngest. Jerry Hembry, the 16-year-old in the front seat, was the oldest.

As Harms looked out, Jerry turned and glanced out the open door. He saw nothing coming.

The City of Denver had been scheduled to pass the crossing at 6:14 a.m.

Now, nearly two hours late, it hustled along at 79 mph, gobbling up 115 feet of track every second.

It was 7:59 a.m.

NEXT: On the cusp