Crossing chapters

Jump to:Related content

Crossing forums

Forum at the Rocky Mountain News in Denver.

Forum at the Rocky Mountain News in Denver.

Forum at the Union Colony Civic Center in Greeley.

Forum at the Union Colony Civic Center in Greeley.

Podcasts:

Acknowledgements

"The Crossing" could only be told with the help of many people:

- The more than 80 people touched by the tragedy of Dec. 14, 1961, who agreed to tell their stories.

- Bill and Mary Bohlender, who helped unearth numerous historic documents and provided numerous insights.

- Virginia Shelton and Mary Shelton Shafer, who provided numerous insights and access to attorney Jim Shelton's files.

- Keith Blue, who provided numerous insights.

- Peggy Ford and the staff at the City of Greeley Museums, Barbara Dey and the Hart Library staff at the Colorado History Museum and former Rocky librarian Carol Kasel, who all assisted with research.

Contact the series team

- Reporter: Kevin Vaughan

- Photographer: Chris Schneider

- Video: Tim Skillern & Laressa Bachelor

- Print designer: Armando Arrieta

- Web designer: Ken Harper

- Web producer: Forrest Stewart

- Web developer: Chris Nguyen

- Copy editor: Dianne Rose

- Photo editor: Dean Krakel

- Imager: Marie Griffin

- Interactive editor: Mike Noe

- Project editor: Carol Hanner

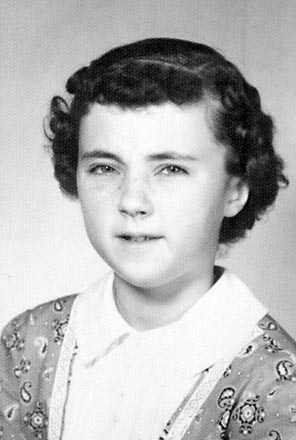

The book is sturdy, bound in a crisp off-white cover. Embossed in gold on the front is its title: "April Showers Brought ... Me!" Written in 1966, when she was a sophomore in high school, it is the autobiography of Nancy Alles.

The chapters, typed neatly on onion-skin pages, have titles any 16-year-old might write, from "My Birth and Family" to "My Summer Vacations" to "My Future Plans."

But one chapter stands out.

Chapter 3, "Dark Memories," begins simply: "The most tragic day in my life occurred on Dec. 14, 1961. On this dreadful day a school bus and a Union Pacific train met at a railroad crossing."

The collision left her wrapped in a body cast for three months, followed by a back brace for six more. It killed her two cousins, Cindy Dorn and Linda Alles.

"I am unable to remember any portion of the actual accident or anything that followed it for three days," she wrote in her book. "I was unconscious during this time. I am very thankful that I was spared the dreadful sights of the accident and the days that followed it.

"I was one of the fortunate ones. I suffered four broken vertebrae and two broken ribs, however."

Forty years after typing those words, Nancy Alles Stroh sits in a blue swivel-rocker in the living room of her home in Oshkosh, Wis. The sun spills down from two skylights and pours through the patio doors that look out on a golf course. Over the past 15 years she has fulfilled her teenage ambition to teach home economics.

She is a pleasant woman who smiles easily, who laughs at memories, who bakes a strawberry pie for visitors, who volunteers to cook at her church camp each summer.

She has faced difficult times. Her marriage gave her two beautiful daughters but ended in divorce. Last April her younger brother, Randy, suffered a heart attack and died on the Weld County farm where she grew up, where her family has been rooted for three generations.

Her religious faith is strong. She prays before each meal. As she talks, she sits beneath a framed needlework piece that reads,

"Life is fragile, handle with prayer."

"I know for sure that out of the worst situation God can bring good from it," she says. "Every bad thing that happens, they are not because God made them happen."

Nancy Alles grew up surrounded by aunts and uncles and cousins who also were her neighbors.

All four of her grandparents were German-Russian immigrants, and they all lived in the Auburn area just a few miles outside Greeley. Her home sat on land where her father, Herman Alles, grew up.

Across the washboard road was the home of her dad's brother, Ruben Alles, his wife, Marie, and their five children. One was her cousin Olinda Louella — Linda to everyone — who was a year younger than Nancy.

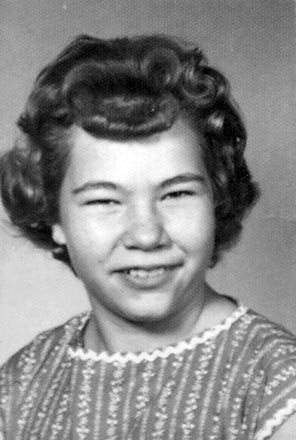

Down the road and around a corner, north of the Auburn school, was the farm of her father's sister, Esther Dorn, and her husband, Herman. They had two children, Wayne and Cindy, who was seven months younger than Nancy.

A grandmother lived a mile away. All around were the farms of her aunts and uncles, eight in all. Today, as Nancy flips through a childhood scrapbook with small black-and-white school pictures pasted on its gray pages, she points to one person after another and says, "He's a cousin" and "She's a cousin."

Her parents farmed 160 acres. Corn. Alfalfa. Pinto beans. Sugar beets. They grew vegetables in the garden for their table, raised cattle and chickens for their meat, milked their own cows.

Doing chores

Some days, young Nancy picked weeds out in the field or collected eggs in the henhouse, a job she didn't like, especially when she had to grab a hoe handle and poke a hen to get her to move off the nest.

Other days, she plucked feathers from newly butchered chickens. She hated that job. As she talks about it, she crinkles up her face, remembering the smell of a dead chicken dunked in boiling water to make it easier to pluck.

For fun, she rode her bicycle down the dirt path that cut through her farm to an irrigation ditch, out to a bumpy gravel road, up to the Auburn school.

She baby-sat for her little brother, Randy, who would hide from her.

"I'd call and call, and then I'd find him and be so mad," she says. "He'd laugh — he thought that was so funny."

Food was plentiful, spiced by the old country — coffee cake they called dina kuchen, krautburgers, dumplings filled with cottage cheese or cherries, noodle soup with butter balls on top, and grebble, a fried pastry dough sprinkled with sugar. There were quilting bees at her grandmother's home, where young Nancy's job was to thread the needles for her aunts.

Her parents knew loss. Three years before Nancy was born, their first child, Larry, got sick with croup and a bad cold. They called a doctor that night. They were told to bring him in the next day.

By morning, Larry was gone.

Herman and Louise Alles endured. They were blessed with Nancy and Randy, a productive farm and a steadfast faith.

A plaster cast

On Dec. 14, 1961, the three cousins got on the bus. Nancy and Cindy were 11; Linda was 10.

In Nancy's memory, it was "just the typical talking and laughing and being kids" kind of morning.

After driver Duane Harms picked up the 36th child, he approached the crossing. Nancy remembers stopping. She doesn't remember what happened next.

"I just remember kind of waking up and hearing moaning and groaning and crying, and then a man came and helped me get to my feet and put me in the back of the station wagon and I went to the hospital," she says.

For three days, she was in and out of consciousness.

Once she was more alert, she wondered where she was and why she was there. A plaster cast covered her body from armpits to hips.

Her parents tried to explain what happened. That's when she found out her two cousins had died.

At the Dorns' small home, Cindy's parents found the cuckoo clock on her bedroom wall had stopped after the accident. It stopped a tick before 8 a.m. — the exact moment the train bashed into the bus.

For a long time, Cindy's parents didn't touch her room. When they finally went through it, they found Christmas cards that Cindy made and hid away — holiday greetings she never got to deliver.

Nancy stayed home for three months, working with a tutor, wearing out fly swatters she slipped down her back to scratch the incessant itching beneath the cast.

She grappled with questions. Why did she survive? Why were Cindy and Linda gone?

"I remember almost feeling guilty that I was here and they were gone," she says. "I just felt so bad for them."

Her Aunt Esther, Cindy's mom, struggled with the death of her only daughter.

"I couldn't help but think, I'm sure as you're watching me grow up, you must be thinking, 'That's what Cindy would look like,'" Nancy says.

Esther would make little comments: "Cindy used to like to do that at Christmas," and "I remember a time when Cindy did that."

A happy morning

Not all the memories of the accident are dark.

As Christmas approached, Nancy was still in the hospital, facing a long recovery. She wanted to be home.

Her parents rented a hospital bed, and on Dec. 23, nine days after the crash, she rode home in the back of an ambulance. She found the hospital bed in the living room, its headboard just a few inches from the Christmas tree covered in brightly colored lights.

She cannot remember the gifts she got — at least not the ones wrapped up under the tree. But she can clearly remember Christmas morning. Her parents stepped up next to her bed and reached out for her.

A moment later, for the first time since the accident, she stood up.

NEXT: New life