Crossing chapters

Jump to:Related content

Crossing forums

Forum at the Rocky Mountain News in Denver.

Forum at the Rocky Mountain News in Denver.

Forum at the Union Colony Civic Center in Greeley.

Forum at the Union Colony Civic Center in Greeley.

Podcasts:

Acknowledgements

"The Crossing" could only be told with the help of many people:

- The more than 80 people touched by the tragedy of Dec. 14, 1961, who agreed to tell their stories.

- Bill and Mary Bohlender, who helped unearth numerous historic documents and provided numerous insights.

- Virginia Shelton and Mary Shelton Shafer, who provided numerous insights and access to attorney Jim Shelton's files.

- Keith Blue, who provided numerous insights.

- Peggy Ford and the staff at the City of Greeley Museums, Barbara Dey and the Hart Library staff at the Colorado History Museum and former Rocky librarian Carol Kasel, who all assisted with research.

Contact the series team

- Reporter: Kevin Vaughan

- Photographer: Chris Schneider

- Video: Tim Skillern & Laressa Bachelor

- Print designer: Armando Arrieta

- Web designer: Ken Harper

- Web producer: Forrest Stewart

- Web developer: Chris Nguyen

- Copy editor: Dianne Rose

- Photo editor: Dean Krakel

- Imager: Marie Griffin

- Interactive editor: Mike Noe

- Project editor: Carol Hanner

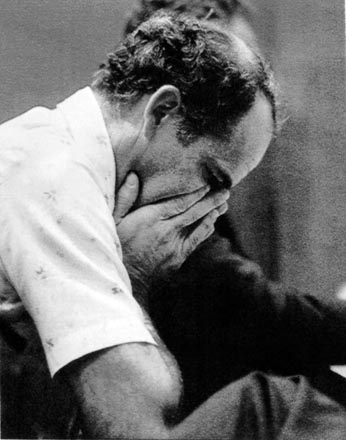

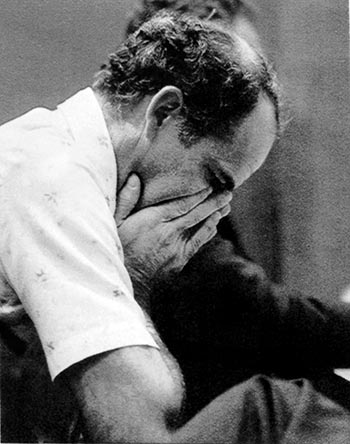

Bob Brantner stood in a Colorado Springs courtroom, waiting to find out whether he would go to prison or go home a free man. Testimony had ground on for two weeks.

Forensics experts had said there was no way his wife could have suffered her fatal head injuries in a fall — even a hard one.

A firefighter said he'd seen drag marks in the master bedroom carpeting but hadn't told police.

Brantner's three sons had given emotional testimony, some of it seemingly at odds with their earlier statements to investigators.

Bob Brantner had spent two days on the witness stand.

He'd detailed life growing up on the farm, the hard work, the push to get through college, the fulfilled dream of becoming a shop teacher.

He'd talked about his marriage to Cheryl, the birth of their three sons and the growing strain in their relationship. He'd told the jury about his affair with a neighbor, which he said was born of his failing marriage.

He'd talked about the fight on Dec. 13, 1992. He said it started after he told Cheryl he wanted a divorce.

And he'd talked about the early morning of Dec. 14, 1992, how he and Cheryl had resumed the argument from the night before, how he'd told her he wanted half of their possessions.

"I told her that I knew the laws of Colorado, and that I was entitled to half of everything we had, and that I would see to it that I got half of everything we had, and at that point, she pushed me," he had said under questioning from one of his attorneys.

He'd told the jury that Cheryl lashed out, shoving him.

When his attorney had asked him, "What did you do?" he'd answered, "When she pushed me, I just put out my hands and pushed back."

He'd detailed the head injury she suffered, the work to stop the bleeding, how he'd helped her to the shower.

He'd told them that when he left the house that morning, Cheryl was in the shower, and the water was running, "and she was fine."

When one of his attorneys had asked him, "On the morning of Dec. 14th, 1992, did you murder your wife?" his answer had come quickly and crisply.

"I did not," he'd said.

40 years

Now it was Feb. 18, 1994. The jury had reached a verdict after five hours of deliberation. The eight men and four women found Bob Brantner guilty of second-degree murder.

Judge Gilbert Martinez ordered him to jail.

In mid-May, Bob stood before Judge Martinez again. The judge sentenced him to prison for 40 years.

A few weeks later, Bob's mother, Katherine Brantner, sat down with a piece of stationery and a pen, determined to tell the judge how wrong he'd been about her son.

To Judge Martinez

Sir: I would like to tell you a story of a young man you have misjudged, Robert Brantner, my beloved son.

In the forty-five years I have known him, was he ever violent, or even short tempered?

We lived and worked our farm of 320 acres. We never had any advantages, and worked for thirty years on a short almost non-existent income. But we raised enough garden, and milked enough cows, so we had plenty to eat. Bob is one of eight children, and worked very hard to get his education. No one handed it to him. He drove insilage trucks, worked in a nursing home, and farmed for the neighbors to get through school. I resented the District Attorney's suggestion that he had every advantage. He could not have been a better father to his three boys. He was a good husband for most of their 24 years of marriage. I don't know what led up to that morning. But he lost it, and really don't remember much of what happened. Except Cheryl was still alive when he left, and told him to go to work.

You really didn't know what kind of man he is, and I know it will do me no good to ask you to help him now. But I wanted you to know, you made a grave mistake.

Sincerely,

Katherine Brantner

Jailhouse lawyer

Bob Brantner has been in prison for 12 ½ years.

His legal odyssey has taken him to Minnesota and to five prisons in Colorado — one of them twice.

For much of the past year, he has been confined at the Four Mile Correctional Center in the sprawling complex of prisons east of Cañon City.

But in those 12 ½ years, one thing hasn't changed: his version of what happened on Dec. 14, 1992, in the master bedroom at the top of the stairs at 5640 Red Onion Way in Colorado Springs.

What happened that day, he says again, was a terrible accident, not a deliberate act of violence.

As he talks, he is no longer a teacher.

He's a jailhouse lawyer now, and he's asking the questions.

If he'd intentionally beaten his wife to death, why was no weapon ever found?

They'd searched his pickup, his shop, his home.

Nothing.

Why did he gather up the bloody bedsheets and a towel and put them in his pickup, and why did he leave them there for the police to find?

"I could have probably left them there," he says. "But I was not thinking of hiding something. That thought never occurred to me."

Instead, he says, he'd simply planned to launder them.

Cheryl made it clear, he says, that she didn't want their boys to know they'd had a fight, to know that she'd gotten hurt.

Finally, he asks another question that his attorneys raised in the trial: Could he have beaten Cheryl to death, then dragged her 228-pound body to the bathtub to make it look like an accident?

He answers the question himself, pointing to his bad knees and bum shoulder and missing finger, calling it a "physical impossibility."

He's got plenty of other questions, too.

Why did other people convicted of second-degree murder in clear-cut cases — a gunshot, a stabbing — get sentences shorter than his?

He points to the case of Susan Hubbell, who was convicted of shooting her husband in the back of the head in a Weld County field just five months after Cheryl Brantner's death.

That conviction was overturned on appeal, and she eventually pleaded guilty to second-degree murder and was sentenced to 10 years in prison for the same charge that resulted in 40 years for Bob.

She was released on parole in May 2003.

And why, in Colorado, are 48.8 percent of the inmates in state prisons beyond their parole eligibility dates?

The answer, says Allison Morgan of the Colorado Department of Corrections, is twofold.

Some inmates don't seek parole, preferring instead to finish their sentences and walk away with no restrictions.

And in deciding whether to release a prisoner, the state parole board considers a number of factors, with public safety at the top of the list.

Bob has other questions.

At $27,587 a year to keep a criminal in a Colorado prison, wouldn't it make more sense to release more of those who are legally eligible to be on parole?

Connections

But some questions leave Bob Brantner groping for answers.

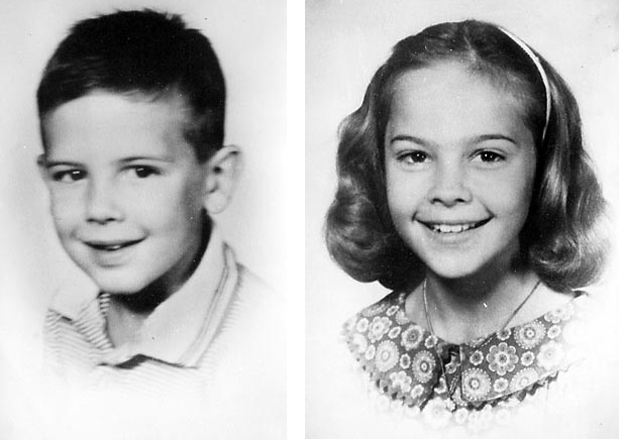

Was there a relationship between Dec. 14, 1961, when Mark and Kathy Brantner died in the bus crash, and Dec. 14, 1992, when Bob's wife died?

The answer, he insists, is "no."

He didn't even make the connection between the two dates until months later when his mother made note of it, he says.

Once he was aware of it, why didn't he tell his attorneys about the terrible trauma his family had endured on that same date so many years earlier?

There was no reason to, he says. It was, he says, just a weird coincidence.

Nothing more.

NEXT: In the shadows