Crossing chapters

Jump to:Related content

Crossing forums

Forum at the Rocky Mountain News in Denver.

Forum at the Rocky Mountain News in Denver.

Forum at the Union Colony Civic Center in Greeley.

Forum at the Union Colony Civic Center in Greeley.

Podcasts:

Acknowledgements

"The Crossing" could only be told with the help of many people:

- The more than 80 people touched by the tragedy of Dec. 14, 1961, who agreed to tell their stories.

- Bill and Mary Bohlender, who helped unearth numerous historic documents and provided numerous insights.

- Virginia Shelton and Mary Shelton Shafer, who provided numerous insights and access to attorney Jim Shelton's files.

- Keith Blue, who provided numerous insights.

- Peggy Ford and the staff at the City of Greeley Museums, Barbara Dey and the Hart Library staff at the Colorado History Museum and former Rocky librarian Carol Kasel, who all assisted with research.

Contact the series team

- Reporter: Kevin Vaughan

- Photographer: Chris Schneider

- Video: Tim Skillern & Laressa Bachelor

- Print designer: Armando Arrieta

- Web designer: Ken Harper

- Web producer: Forrest Stewart

- Web developer: Chris Nguyen

- Copy editor: Dianne Rose

- Photo editor: Dean Krakel

- Imager: Marie Griffin

- Interactive editor: Mike Noe

- Project editor: Carol Hanner

Vicky Munson Allmer lay in her bed, the lighted dial of a clock above her. It was 3:30 a.m., and up until that very moment she didn't know how she could go on living. A few months earlier, she had lost her teenage son.

She was convinced that nothing short of divine intervention would keep her on earth. She couldn't imagine holding up under the pain she felt.

Then, with that clock above her, a different feeling rushed over her.

"I don't want to die," she thought. "I want to live."

Vicky had been one of the fortunate ones on Dec. 14, 1961. She and two brothers had survived the school bus-train collision at the crossing.

"Vicky's hurt pretty bad, but I guess we were lucky," her mother told a reporter that day.

A quarter-century later, as Vicky lay in bed early that morning, she didn't feel lucky.

But she felt, for the first time she could remember, that she could go on.

Day of confusion

Raymond and Jean Munson had eight children by 1961 — and little money. Vicky remembers their two-room shack with no refrigerator and no running water. She remembers keeping their milk and butter in the shade on the north side of the house to keep it cool.

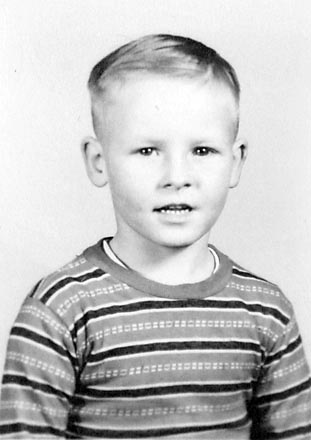

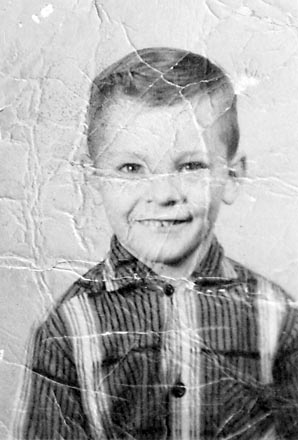

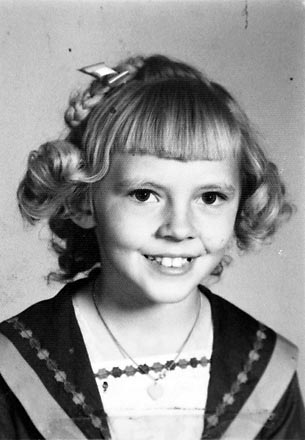

Three of the Munson children rode the school bus that fall to Delta Elementary School outside Greeley. Vicky was 6. Her brother William John — everyone called him Johnny — was 9, and her brother Gary was 8. On any other morning they'd have been among the last students picked up — past the crossing that turned deadly.

But on that snowy morning, with the temperature sitting at 6 degrees, Raymond drove his children to the now-closed Auburn school. Bus driver Duane Harms lived next door with his wife and 3-week-old baby. The bus idled out front, warming up as the Munson kids climbed in. They sat down behind the driver's seat, near the heater, before Harms had even begun his route.

A little more than a half-hour later, the train smashed into the school bus.

In the confusion after the accident, Raymond rushed to the Delta school to see if his kids were there. Instead, he found the assistant principal, Keith Blue, and the two grabbed a box of first-aid supplies and drove the four miles to the crossing.

Over the next couple of hours, Raymond rushed from the scene to the hospital to the old state armory building on Eighth Avenue in Greeley, where they'd taken the dead. He found Johnny and Gary alive, but he couldn't find Vicky.

If Vicky's dead, he told his wife, he would take all her clothes and burn them so he wouldn't have to remember her.

Vicky didn't die.

The collision knocked her unconscious, split open her forehead and burned her lower right leg.

It broke Johnny's left arm, scraped up his face and left a piece of metal embedded in his spine.

Gary and several other children had gotten up and walked to a nearby farmhouse.

"I didn't see a thing," Johnny told a newsman who snapped his picture in the hospital, "but I'm sure glad I wasn't killed."

Losing Jimmy Joe

The trauma of the bus accident was bad enough. But tougher times awaited the Munsons.

James Joseph Munson — Jimmy Joe to his family — had white-blond hair and blue eyes. He was 8 years old the day he died in June 1968.

He was out on the farm with Raymond, playing while his father ground hay. While Raymond worked, Jimmy Joe got too close to the tractor's "power take-off" — a potentially lethal spinning steel shaft. It caught his nylon coat and battered his small body against the iron tongue of the hay wagon.

The ambulance was delayed by a train. After the medics finally got there, Jimmy Joe said, "Mommy and Daddy," and died.

Vicky was 13. The death of her little brother devastated her. She figured God was punishing her for some deed unknown, and she spent the rest of her teenage years trying hard not to do anything wrong.

Jell-O in the snow

It's strange the things that stick in people's minds when something bad happens.

Jean Munson would tell her children that on the morning the train hit the school bus, she remembers them getting into a fight over a bowl of red Jell-O that she'd set out in the snow to harden.

Until he died in 1973, Raymond Munson would always think of The Lion Sleeps Tonight playing on the radio the night before the accident.

Many years later, Vicky would hear the song and think of her dad. And she would feel good.

In the jungle, the mighty jungle

The lion sleeps tonight.

In the jungle, the quiet jungle

The lion sleeps tonight.

Near the village, the peaceful village

The lion sleeps tonight.

Near the village, the quiet village

The lion sleeps tonight.

Hush my darling, don't fear my darling

The lion sleeps tonight

Hush my darling, don't fear my darling

The lion sleeps tonight.

Fading scars

Vicky talks slowly, deliberately. Her long, dark-blond hair frames her face. The scar down her forehead — the one that doctors said would leave her permanently disfigured — has faded gradually over the years, mirroring the slow healing inside. The faint line is noticeable today only when the light catches it just right.

She is 51 now, and she lives in a second-floor apartment with her Persian cat, Girl. She has worked as a licensed practical nurse since 1976, the last 20 at a retirement home.

She doesn't talk often with her two brothers who were with her on the bus. John lives in Washington state. Gary lives in Evans, outside Greeley. Their mother lives in Greeley, and Vicky visits her every week or two.

Vicky's journey from the little girl who survived the bus accident to the middle-aged woman who survived a broken heart was not a smooth one.

In a span of less than two years in the late 1980s, she lost her 15-year-old son, David "Barnes" Allmer, and two brothers, Randy, 24, and Delbert, 32. The deaths are still so close to the bone, so personal, that she doesn't want to talk about them.

For the longest time after those losses, she could not imagine that she could survive.

She tried to fight through it.

Seeing a counselor didn't help. Then she took a class on death and dying, required as part of her nursing work. The books had a term for her kind of pain. They called it "complicated grief," and they were right.

The turning point came that morning she awoke and realized she wanted to keep living.

It wasn't easy. Years, it seemed to her, passed while she did almost nothing but work and sleep. But in the end, she found her way back to peace, and to life.

She did it with the help of God.

She lay in bed at night and prayed, "God, speak to me."

She slept with a Bible opened across her chest, trying to soak in its power.

"I believe that it took many acts of God to keep me alive," she says.

She came to realize that some things just can't be explained.

"If this is what I have to endure in life," she says, "Jesus Christ endured much greater for me, being I'm a sinner and made of the dust, and he is my redeemer."

The healing came in a series of revelations.

"I had to finally — how many months and years later, I don't know — I had to bow not to my will but to God's will for me," she says.

"And that took a lot of doing, but now I'm at peace, and God taught me of his power, and I believe that I've walked very close to the power of God."

Just last week, she lost another brother, Roger, 35. She asked God to help her as she began another journey through grief.

For a long time, she wished she had been taken at the crossing so she could have avoided the pain that came later.

"I was young, and I wouldn't have known," she says. "I would have just been gone."

But now she's glad she's here. She's glad her parents never had to know the pain of losing her.

NEXT: Coincidence