Crossing chapters

Jump to:Video

School bus driver Duane Harms begins picking up children on what starts as a typical day.

Watch video

Watch video

Related content

Crossing forums

Forum at the Rocky Mountain News in Denver.

Forum at the Rocky Mountain News in Denver.

Forum at the Union Colony Civic Center in Greeley.

Forum at the Union Colony Civic Center in Greeley.

Podcasts:

Acknowledgements

"The Crossing" could only be told with the help of many people:

- The more than 80 people touched by the tragedy of Dec. 14, 1961, who agreed to tell their stories.

- Bill and Mary Bohlender, who helped unearth numerous historic documents and provided numerous insights.

- Virginia Shelton and Mary Shelton Shafer, who provided numerous insights and access to attorney Jim Shelton's files.

- Keith Blue, who provided numerous insights.

- Peggy Ford and the staff at the City of Greeley Museums, Barbara Dey and the Hart Library staff at the Colorado History Museum and former Rocky librarian Carol Kasel, who all assisted with research.

Contact the series team

- Reporter: Kevin Vaughan

- Photographer: Chris Schneider

- Video: Tim Skillern & Laressa Bachelor

- Print designer: Armando Arrieta

- Web designer: Ken Harper

- Web producer: Forrest Stewart

- Web developer: Chris Nguyen

- Copy editor: Dianne Rose

- Photo editor: Dean Krakel

- Imager: Marie Griffin

- Interactive editor: Mike Noe

- Project editor: Carol Hanner

At 6:41 on the icy Thursday morning of Dec. 14, 1961, a Union Pacific streamliner lurched away from the station in Sterling, one hour and 41 minutes behind schedule.

An unusually heavy volume of Christmas mail had delayed the train at a number of stops. Now it was starting the last leg of the overnight Chicago-to-Denver run, with 173 passengers aboard.

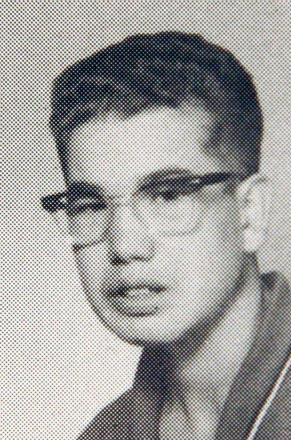

Engineer Herbert F. Sommers, in his OshKosh overalls and wire-framed glasses, opened up the throttle in the cab of the lead locomotive. Fireman Melvin C. Swanson sat across from him.

The three diesel locomotives growled, and soon the 16-car train clipped along at close to 80 mph.

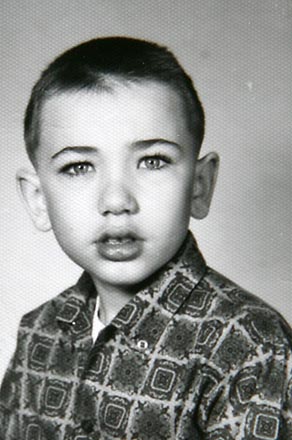

Ninety miles away in the small Weld County farming community of Auburn, Duane Harms faced the same bitterly cold morning.

The 23-year-old school bus driver, a slender man with reddish-blond hair and freckles, had tried college, but struggled.

Now he had a job with School District No. 6, driving a bus in the morning and afternoon along a latticework of straight gravel roads.

During the day, he worked as an elementary school janitor.

He and his wife of 2 1/2 years, Judy, had a 3-week-old baby, Lynda, who had been born the day after Thanksgiving.

Judy was a student at the state college in Greeley, working toward a teaching degree. She and Duane lived next to the old Auburn school in an 800-square-foot home originally built for the teacher.

Five miles southeast of Greeley, the Auburn area had no general store, no post office.

Simple frame houses stood along its straight, bumpy roads. Sugar beets, corn, alfalfa and pinto beans grew in its vast, flat fields.

The families who lived there were first-, second- and third-generation immigrants — German-Russian, Swedish, Mexican — with names like Alles, Geisick, Munson, Brown, Rangel and Ford.

They drove into Greeley, or to Platteville or Gilcrest, to worship. They went to Catholic, Baptist and Congregational churches.

For three generations, children had taken their lessons in the Auburn school's classrooms, played ball out by the backstop.

But the school was closed, and now, for the first time, the farm kids of Auburn rode a bus into Greeley.

Harms had arisen at 5:30 a.m. At 7 a.m., he closed his front door behind him as he headed out to the 60-seat school bus parked in the yard.

He started the engine of bus No. 2, then hurried back inside while it idled. This was his morning ritual on cold days — he wanted the children to find warm seats waiting for them, and he knew he'd be arm-wrestling the stick shift if he didn't get the engine going.

The Union Pacific

Seventy miles away, the train cut across the lonely landscape of northeast Colorado — past the no-stoplight towns of Atwood, Merino and Hillrose as the tracks paralleled the South Platte River.

Union Pacific streamliners ferried passengers in relative luxury, rocketing through the night across rural America. They had impressive-sounding names. The City of Los Angeles. The City of Portland. The City of Denver.

Sommers, the engineer, had been married for 39 years and had no children. He'd started with the railroad in October 1918, a month before the signing of the armistice that ended World War I. By 1941 he'd been promoted to engineer.

As the fall of 1961 approached — just as Duane Harms was beginning to drive a school bus — Sommers had grabbed a coveted slot on the City of Denver, one of the regular trains that moved passengers across the West in the days before air travel was commonplace.

Sommers, based in Denver, would leave the city in the afternoon and run the eastbound train as far as Sterling, 125 miles away.

There, he'd climb down from the engine and head off the clock while another engineer took the next leg of the overnight trip.

Early the next morning, Sommers would take over the returning City of Denver and run it over the last stretch back into Union Station.

On this day, the train reached Fort Morgan, 40 miles from Greeley, around 7:30 a.m. The sun had cracked the eastern horizon 15 minutes earlier.

About the same time, Harms said goodbye to Judy and Lynda, stepped into the bus and started the defroster.

The windshield was clear, but the 6-degree weather had iced over the windows along the sides and back.

Harms found three children waiting for him in the first two rows behind his seat.

Normally, he would pick up Vicky, Gary and Johnny Munson near the end of his run. But their father, Raymond, didn't want them to wait out in the cold, so he dropped them off at the bus.

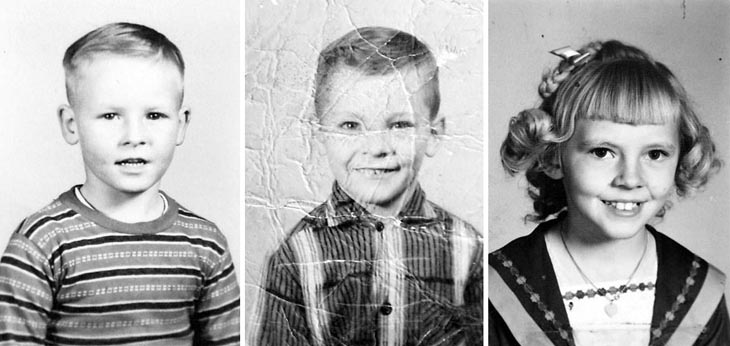

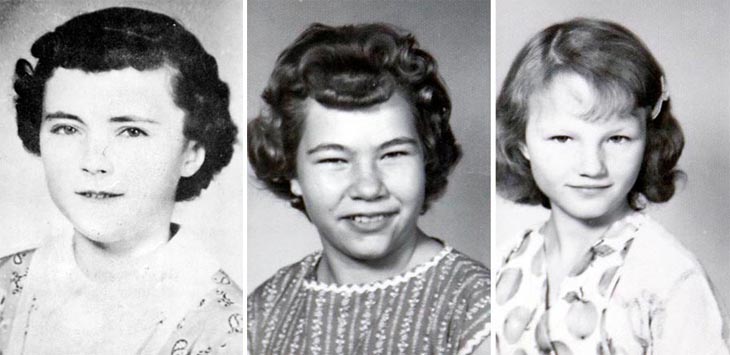

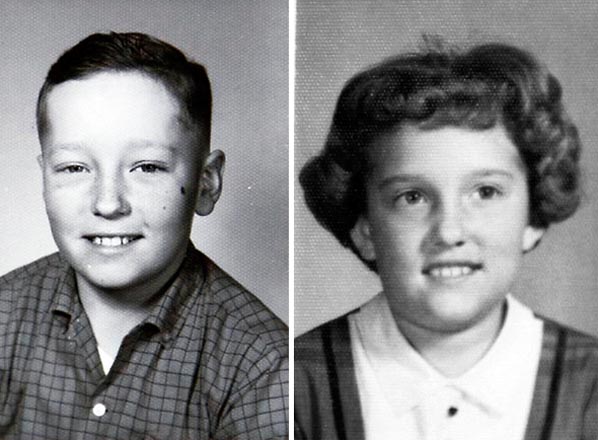

Vicky, 6, was a first-grader. Gary, 8, and Johnny, 9, were third-graders.

Harms put the bus in gear, pulled out and turned right to head north.

A couple hundred yards away, he stopped, grabbed the big chrome lever to his right and yanked open the folding door. Cindy Dorn, an 11-year-old sixth-grader who rode the bus each day with two of her cousins, hopped on and took a seat farther back in the bus.

On any other day it wouldn't matter where a child sat. But this day would be different. This day, it would be a matter of survival.

Hitching a ride

Down the road, 13-year-old Roger Reps stood at the end of his driveway.

He could see the school bus in the distance.

Normally he waited with his brother, Jimmy, but the 15-year-old was sick.

Just then, a neighbor pulled up and offered Roger a ride to town. The boy didn't know what to do.

"C'mon," the man said, and Roger opened the door and got in.

A little farther up the road, Harms passed by the home of another girl who was staying home sick.

Then he pulled up in front of the home of Eldon and Genevieve Yetter.

Harms usually picked up three passengers at this stop — the Yetter girls, Colleen, 13, and LaDean, 6; and their cousin, Jerry Hembry, 16, who lived with the family and was a sophomore at Greeley High School.

But Colleen and LaDean were moving slowly. They'd been out late the night before at a Christmas program rehearsal at their church.

LaDean's hair needed to be combed. Colleen wasn't ready, either.

Jerry was.

He pulled on his jacket and sprinted down the long driveway to catch the bus.

Though he usually sat about four rows back, he plopped down into the front seat, just behind the door, a deck of cards in his jacket pocket to help pass the time.

Harms pulled away.

At the next stop, along U.S. 34, Harms picked up the three Freeman children — Melody, 8, Joy, 10, and their brother, Smith, 7 — and Sherry Mitchell. Sherry, 6, had wanted to go to the hospital to see her dad, who had been injured by a steer at the meatpacking plant where he worked. But her mother decided Sherry should go to school and carried her to the bus as tears streamed down the girl's face.

Holiday time

At the next corner, Harms stopped for 8-year-old Randy Geisick, who clutched some wrapping paper as he took a seat up front.

He and his classmates had made Christmas gifts for their parents, and he was going to wrap his at school.

A little ways down the road, Harms picked up Alan and Debbie Stromberger. Alan, 10, took a seat in the second or third row. Debbie, 7, headed toward the back and sat down to pull on her galoshes.

Along this stretch of road, Harms missed more regulars — sisters who got a ride into town with their parents.

At the next intersection, Harms stopped for 13-year-old Cheryl Brown.

In her wallet was a Confederate $5 bill she'd found in the wall of her home.

Harms turned right and headed back west toward his starting place.

Before he got there, he stopped for the Alles girls.

Nancy Alles, 11, lived on the south side of the road, on a farm where her father had grown up. Her cousin, Linda Alles, 10, lived on the north side.

Both girls were cousins to Cindy Dorn, the first passenger Harms had picked up.

Nancy Alles sat next to Cheryl Brown in the fourth row. Cheryl pulled out her social studies papers to study for a test.

Linda Alles, carrying her brother's wrestling medal for show-and-tell at school, took her normal seat near the back of the bus.

After pulling away from the Alles homes, Harms drove back past the old Auburn school.

He'd driven a touch over four miles, cutting a giant square across the countryside.

He took a left and headed down the road about a half mile, where he stopped at the farm of Ed and Betty Heimbuck for their two girls, Pam, 9, and Kathy, 12.

Just after they got on the bus, Harms pulled up to a set of railroad tracks and stopped.

It was about 7:45 a.m.

The City of Denver streamliner raced along, less than 20 miles — and 15 minutes — away.

NEXT: A typical morning