Crossing chapters

Jump to:Related content

Crossing forums

Forum at the Rocky Mountain News in Denver.

Forum at the Rocky Mountain News in Denver.

Forum at the Union Colony Civic Center in Greeley.

Forum at the Union Colony Civic Center in Greeley.

Podcasts:

Acknowledgements

"The Crossing" could only be told with the help of many people:

- The more than 80 people touched by the tragedy of Dec. 14, 1961, who agreed to tell their stories.

- Bill and Mary Bohlender, who helped unearth numerous historic documents and provided numerous insights.

- Virginia Shelton and Mary Shelton Shafer, who provided numerous insights and access to attorney Jim Shelton's files.

- Keith Blue, who provided numerous insights.

- Peggy Ford and the staff at the City of Greeley Museums, Barbara Dey and the Hart Library staff at the Colorado History Museum and former Rocky librarian Carol Kasel, who all assisted with research.

Contact the series team

- Reporter: Kevin Vaughan

- Photographer: Chris Schneider

- Video: Tim Skillern & Laressa Bachelor

- Print designer: Armando Arrieta

- Web designer: Ken Harper

- Web producer: Forrest Stewart

- Web developer: Chris Nguyen

- Copy editor: Dianne Rose

- Photo editor: Dean Krakel

- Imager: Marie Griffin

- Interactive editor: Mike Noe

- Project editor: Carol Hanner

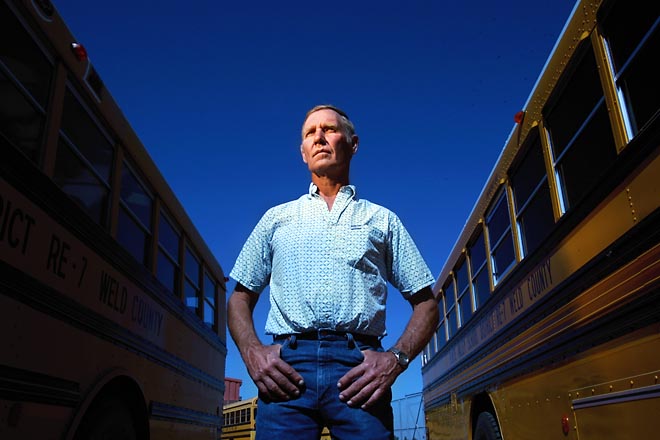

Glen Ford never expected it would turn out this way.

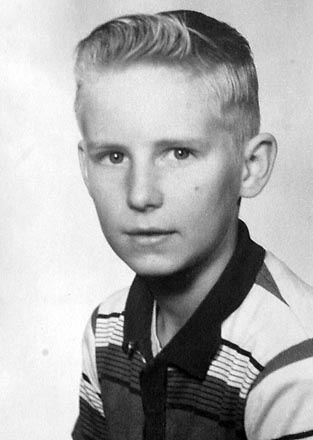

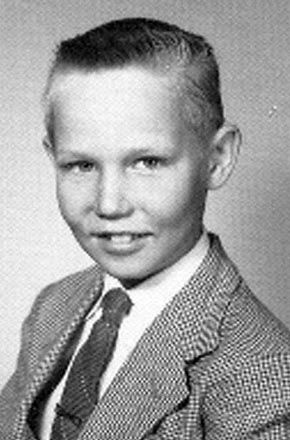

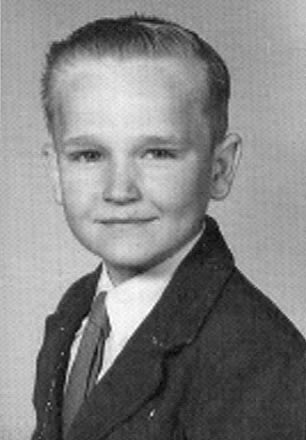

His cowboy hands grip the steering wheel of a school bus, 45 years after he survived a school bus-train collision that killed his older brother.

He logs 160 miles a day. He crosses railroad tracks 29 times.

On this morning, he is in the driver's seat in the darkness, his face illuminated only by the instruments on the dashboard, the diesel engine grumbling beneath him.

The digital clock beside the gauges glows red: 6:49 a.m.

He's got plenty of time.

He has a good 10 minutes before he needs to get going on his morning route for the Platte Valley School District.

It will take him across the farm fields around Kersey, though Greeley and Milliken and Johnstown and back.

The heater whirs. The defroster hums.

Every few seconds, the wipers slide back and forth with a whump.

It's a typical morning. Just as Dec. 14, 1961, was a typical morning.

Glen, 56, warms up his bus. Just as Duane Harms got up early to warm up his bus on that fateful morning four and a half decades ago.

Railroad crossings await him. Just as they awaited Duane Harms.

'A piece of cake'

In 1980, Glen Ford and his wife, Jane, bought a 35-acre slice of the farm he and his brothers had lived on as boys.

Many of the families he had known as a kid had moved on. The Brantners had sold their 320-acre farm. The Paxtons were long gone from their place across the road.

A few remained. The Walsos. The Alles families.

The area still looked much as it had. A few of the old houses with clapboard siding had been moved or torn down. Newer brick homes stood in their place.

The home where Glen and his brothers romped as boys was gone, replaced by a larger house.

But on a clear day, Longs Peak still loomed majestically to the west. Pinto beans, corn, sugar beets and alfalfa still sprouted in the wide-open fields.

In the Ford home, cowboying was a way of life. Glen made a good living on the rodeo circuit for two decades, riding bareback, climbing onto bone-snapping bulls when he needed extra cash.

His brother Bruce was even more successful, winning the world bareback-riding title five times, becoming a legend in the process.

Rodeo still courses through the family's veins.

Glen's oldest son, 29-year-old Heath, is a top bareback rider, and 26-year-old Jarrod is a top bull rider.

And Bruce's son, 25-year-old Royce, has flirted with the very top of the bareback world.

Even Nic, Glenn's youngest son at age 23, is on the rodeo circuit, at the wheel of a Dodge pickup, shuttling Jarrod from rodeo to rodeo, making travel arrangements.

It's the life Bruce and Glen lived for decades.

But in 1984, Glen could see the day coming when he would no longer compete.

One day, Jane called him at home.

The Kersey school district, where she was a teacher, needed a school bus driver.

Almost on impulse, Glen drove to the administrative office and filled out the paperwork. He figured it might help pay the light bill for a while.

More than 22 years later, he is still at it.

The work is easy in many ways — "a piece of cake" he calls it.

But there's one hazard that's on his mind every day: railroad crossings. He thinks about them even when he's not on the job. Sometimes, early in the morning, when he's lying in bed, a train whistle will blare somewhere off in the distance.

The tracks pass by just a half mile away from his home on the farm where he grew up.

Those tracks are seldom used these days; the Union Pacific ended passenger train service on May 1, 1971.

But each time he hears that whistle, he thinks the same thing.

"You better be looking for him, because you never know when that train's going to be coming through, still," he says. "It isn't going as fast as it used to, but it doesn't have to be going fast to hit you."

Morning rounds

It's now 7 a.m. The bus is warm.

The odometer shows a tick more than 181,000 miles, almost all of them Glen's.

He reaches for the shift lever in front of him and slides the transmission into reverse, backs up, moves it into drive, then accelerates slowly out of the fenced yard where the buses are kept.

"Don't get seasick now," he says, and smiles as the cumbersome bus rocks back and forth. A few minutes later, he is at his first railroad crossing, on the edge of Kersey.

The rails in front of him carried the Union Pacific train that smashed into his bus more than 45 years ago.

He goes through a ritual he will repeat many times this day.

Slide open the window to his left. Push open the door to his right. Look one way, then the other.

Convinced it's clear, he steps on the gas pedal, and the bus jostles across the tracks and starts up a hill.

He heads down a long, straight, narrow county road, turns off the pavement onto another long, straight, narrow county road. The bus jiggles over the washboard surface.

As he drives, he talks about how much he likes the work, how little effort it requires.

"It's about like getting up and driving to the coffee shop is what it amounts to," he says. "And they pay you for it."

These days his route takes him to the homes of youngsters with special needs.

He wheels into the yard of a farm home, drives around the lane that goes behind the home and stops near the front door.

A little girl comes out. Glen opens the door and gets out of his seat.

"Good morning, Maria," he says.

The little girl climbs up the steps and heads to the back of the bus.

His route takes him back through town.

"Good morning," he says as another girl gets on the bus. He waves to the girl's father, who stands in the doorway of his home.

Farther along, he pulls up a long lane to a driveway, backs up, turns around and stops in front of a big brick home. He gives the horn a blast, and a boy comes out, gets on.

"What's happening?" Glen asks.

He pulls away. The children sit in silence as he steers the bus back onto a county road.

"I'm sure they're a little more quiet than Duane's were, because I was one of them. It was no piece of cake for him," he says.

After a stop in Greeley, he heads south.

Near Milliken, he approaches a crossing where the tracks are at an angle. He pulls up, stops, opens the door and window. It's easy to see to his left.

But he has to twist in his seat and look back, over his right shoulder, to see the tracks to the right.

That's how it was that morning in 1961 at a different crossing in Weld County.

Duane Harms never saw the train that slammed into his bus, pummeling 11-year-old Glen, injuring his 9-year-old brother, Bruce, and killing his 13-year-old brother, Jimmy.

On this day, this crossing is clear.

'Nothing he could do'

At each crossing, Glen thinks about Dec. 14, 1961.

Each time he goes by the spot where that accident happened, he thinks about it. The site is less than 1 1/2 miles from his home, and he passes it four times on some days.

All those thoughts, and all those years at the wheel of a bus, have given Glen Ford a perspective on Duane Harms that perhaps no one else has.

"That guy was a good guy," he says. "As far as I'm concerned, he didn't make no mistake. Anybody would have made that one. There was nothing he could do for it."

A number of factors added up to tragedy, he says.

A bad crossing.

Frosted bus windows.

Haze in the air.

A late train.

Utility poles that obscured the view.

"I felt that way from the day after the wreck," he says. "I never did hold it against Duane. Some of the parents wanted to crucify the guy. It would have happened to them if they would have been driving that day."

Then Glen offers a startling assessment.

"That guy loved them kids," he says. "I mean, he went through a lot of torture knowing that kids were killed. He loved them all.

"He's a better bus driver than me. Sometimes, I don't love them all."

NEXT: Alive