Crossing chapters

Jump to:Video

Memories of the long-ago accident still surface at odd times for Alice Larson Richardson.

Watch video

Watch video

Related content

Crossing forums

Forum at the Rocky Mountain News in Denver.

Forum at the Rocky Mountain News in Denver.

Forum at the Union Colony Civic Center in Greeley.

Forum at the Union Colony Civic Center in Greeley.

Podcasts:

Acknowledgements

"The Crossing" could only be told with the help of many people:

- The more than 80 people touched by the tragedy of Dec. 14, 1961, who agreed to tell their stories.

- Bill and Mary Bohlender, who helped unearth numerous historic documents and provided numerous insights.

- Virginia Shelton and Mary Shelton Shafer, who provided numerous insights and access to attorney Jim Shelton's files.

- Keith Blue, who provided numerous insights.

- Peggy Ford and the staff at the City of Greeley Museums, Barbara Dey and the Hart Library staff at the Colorado History Museum and former Rocky librarian Carol Kasel, who all assisted with research.

Contact the series team

- Reporter: Kevin Vaughan

- Photographer: Chris Schneider

- Video: Tim Skillern & Laressa Bachelor

- Print designer: Armando Arrieta

- Web designer: Ken Harper

- Web producer: Forrest Stewart

- Web developer: Chris Nguyen

- Copy editor: Dianne Rose

- Photo editor: Dean Krakel

- Imager: Marie Griffin

- Interactive editor: Mike Noe

- Project editor: Carol Hanner

Alice Larson Richardson spent most of a lifetime not talking about Dec. 14, 1961.

She didn't visit it in her mind. She didn't bring it up with her parents.

But sometimes, with no warning, the crossing would come to her.

On a cold December day in 1998, she stood in the brown grass at Sunset Memorial Gardens on Greeley's west side to say goodbye to her Aunt Winnie Jo.

Alice's older sister, Linda Edstrom, turned to her during the graveside service.

"Alice," she said, "look down."

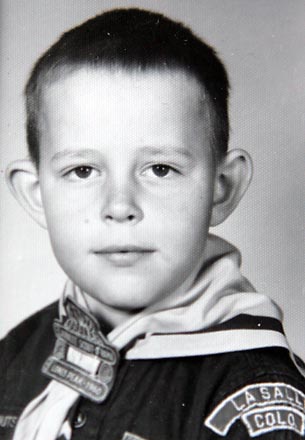

There, below Alice, was a simple marble gravestone sunken into the ground. Etched on three weathered brass plates were the name "Steven A. Larson" and two years, 1952 and 1961.

It was the first time Alice had ever seen the grave of her little brother, the one who had switched seats with her on the bus just before the crash 37 years earlier.

Emotions welled up in her.

Sadness, for the boy whose face she sometimes had trouble remembering.

A twinge of jealousy, that Linda had known where their brother's grave was and she had not.

Regret, that she'd let so many years pass without coming to find this spot.

No memory of the day

It hurt.

That was the first thing Alice Larson knew when she awakened in the hospital several days after the collision.

Doctors had taken out her crushed gallbladder and appendix and a piece of her liver. They'd put a half-cast on her fractured right hand.

They'd patched up her cuts and scrapes.

Now, finally, she was aware of what was going on around her. She turned her head.

She saw her father sitting in a big blue chair.

Alice was confused. She didn't know why she was in the hospital. She couldn't remember the accident.

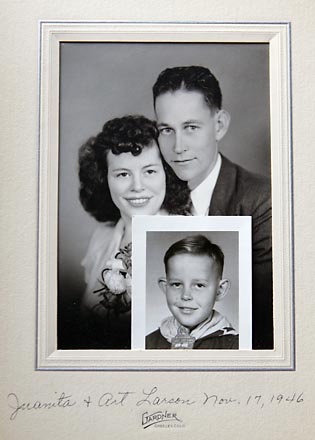

"Oh," said Art Larson, a skinny truck driver who grew alfalfa for the cows and horses on his 23-acre farm, "you're finally awake."

Her father told her a train had hit the school bus, that a few of the children had been hurt, that she was recovering, that everything was fine.

On a doctor's advice, he didn't tell her that 20 children had died; that the two girls sitting on either side of her, Mary Lozano and Kathy Brantner, were gone; that her little brother, Steve, had already been buried.

He didn't tell her he'd stood up for bus driver Duane Harms.

During her three weeks in the hospital, Alice kept asking why Steve and her older sisters, Nancy and Linda, hadn't visited.

The answer was always the same: They're not allowed up here.

One night, Alice awoke in the dark and heard Jacquelyn White crying in the bed next to her.

A nurse was trying to comfort the girl.

As Alice listened to the muffled conversation, she realized that Jacquelyn's sisters, Elaine and Juleen, were dead.

That didn't make any sense. Did they get in a car wreck on the way to the hospital to visit Jacquelyn? Hadn't her father told her that only a few people had been hurt?

"Shhh," the nurse suddenly said, "I think Alice is awake."

The day before Alice was well enough to go home, her mother came into her room. She had something to tell Alice.

"The wreck," she said, "was a little bit worse than we told you."

"I know," Alice answered. "Elaine and Juleen are dead."

"So is Steven," her mother said.

Alice broke down.

But her mother also had a surprise. Linda and Nancy were waiting for her.

They were shocked at how pale and thin Alice was, but the sisters were happy to see each other.

When Alice arrived home from the hospital, Steve's things were gone.

One day, during the months of doctor visits, her mom wheeled the car into Sunset Memorial Gardens. She pointed out some of the graves to Alice — Steve is over there, the Paxton girls are over there, she said.

They never got out of the car.

Moving on

For the rest of Alice's childhood, the accident simply wasn't spoken of. That's just how things worked — no grief counseling, no working through the sorrow out loud.

Not talking about it was easy. Not acknowledging that life had changed was more difficult.

One night, her mother set the table for six.

Then she remembered.

She didn't need a place for Steve, the chubby baby who'd fought rheumatic fever. The boy who'd smashed his thumb on the old iron gate at the Auburn schoolhouse, then calmly examined the mangled flesh at the doctor's office and said, "I really did it up that time, didn't I, Mom?"

Alice found solace in the outstretched arms of her blue teddy bear.

A mother who lost her daughter in the bus crash had donated it to the gift exchange for the sixth-grade class.

Alice got it, and she loved it.

Her body healed, but she was extremely self-conscious about her scars and the long-healed scrapes on her face that turned splotchy red when she got tired.

When she dressed for gym, she'd hide her incisions.

When her friends started wearing bikinis, she stuck to an old one-piece.

One night, she got all dressed up for a high school dance and twirled around the living room for her parents.

"You have a big hole in your nylons," her father told her.

She looked down. It wasn't a hole. It was a scar on her leg, showing through her stockings.

Alice graduated from high school, studied business management in Denver and took a job in the credit office of the hospital where she'd been a patient after the crash.

She married Ron Richardson, a Weld County deputy sheriff.

Though the accident was never discussed, Alice was surrounded by it every day.

She and Ron built their home on East 20th Street in Greeley, on the same piece of ground where Delta Elementary School once stood — the school she never reached on that frigid December morning in 1961.

Their four daughters — Rhonda, Melissa, Kynda and Tawnya — attended East Memorial Elementary, opened in 1963 and named in honor of the children who died.

Every time she walked down the school's main hallway for a parent-teacher conference or a holiday program, she walked past a brass plaque listing those 20 names, with Steven Arthur Larson in the middle row.

She was doing well, happy, with a great family, but every so often, the memories ambushed her.

She had told her children about the crash, and one day Kynda announced that she planned to write about it for her college English composition class.

But Alice couldn't answer many of Kynda's questions, so she sent her to the library.

Kynda came home with copies of newspaper stories, and Alice sat down to read them.

They overwhelmed her.

"I lived through it," she says, "so I didn't think that reading about it would be as hard as it really was. . . . I guess I just spent all those years acting like an ostrich — if I don't know about it, I don't have to think about it, or deal with it, or something. I don't know why."

'I don't like this.'

Sometimes the pain was more visceral.

When Melissa was a third-grader, Alice volunteered to help shuttle youngsters from East Memorial to the University of Northern Colorado for swimming lessons.

For many years after the accident, Greeley school leaders required an adult "monitor" on each bus. It was the monitor's job to get out at every railroad crossing and wave the bus forward if the tracks were clear.

Alice agreed to monitor the swimming trips. She'd ridden the bus after the accident, and it had never bothered her.

The day came. Alice sat in the front seat. At a railroad crossing in Greeley, Alice stepped out of the bus.

As she started across the tracks, her knees shook.

"Why am I doing this?" she thought.

Panic grabbed her, for no reason and every reason.

As she tried to calm herself, she felt the awesome responsibility of keeping this busload of kids safe.

The bus crossed, went on to the college and picked up another group, fresh from the pool. At another crossing, the same thought returned — "Why am I doing this?"

Then another one hit her: "I don't like this. I don't like it at all."

She took one step down toward the street. A train whistle reverberated in the distance.

She froze on the bus steps. The train wasn't in sight. The red crossing lights were off. The bells were silent. The red-and-white striped arms remained up.

Finally, the bus driver said, "Sit back down, Mrs. Richardson."

She moved shakily back to her seat.

In a few moments, she would carry out her duties, but for a time she just sat there.

The children, antsy in their seats, didn't understand the delay.

This is stupid, one said, we could make it.

We had plenty of time to get across, another one said.

Alice sat there.

"Sometimes," she said, "you don't."

NEXT: Driver's seat