Crossing chapters

Jump to:Related content

Crossing forums

Forum at the Rocky Mountain News in Denver.

Forum at the Rocky Mountain News in Denver.

Forum at the Union Colony Civic Center in Greeley.

Forum at the Union Colony Civic Center in Greeley.

Podcasts:

Acknowledgements

"The Crossing" could only be told with the help of many people:

- The more than 80 people touched by the tragedy of Dec. 14, 1961, who agreed to tell their stories.

- Bill and Mary Bohlender, who helped unearth numerous historic documents and provided numerous insights.

- Virginia Shelton and Mary Shelton Shafer, who provided numerous insights and access to attorney Jim Shelton's files.

- Keith Blue, who provided numerous insights.

- Peggy Ford and the staff at the City of Greeley Museums, Barbara Dey and the Hart Library staff at the Colorado History Museum and former Rocky librarian Carol Kasel, who all assisted with research.

Contact the series team

- Reporter: Kevin Vaughan

- Photographer: Chris Schneider

- Video: Tim Skillern & Laressa Bachelor

- Print designer: Armando Arrieta

- Web designer: Ken Harper

- Web producer: Forrest Stewart

- Web developer: Chris Nguyen

- Copy editor: Dianne Rose

- Photo editor: Dean Krakel

- Imager: Marie Griffin

- Interactive editor: Mike Noe

- Project editor: Carol Hanner

The two men visit the grave from time to time, but they never go together.

The pink granite headstone sits at the west end of Linn Grove Cemetery outside Greeley, just a few steps from the graves of two other children who died the day the train cut through the school bus.

Spelled out in big block letters is the name both men share.

FREEMAN

And the name of the little girl they both miss.

April Melody

Feb. 20, 1953 — Dec. 14, 1961

The headstone carries the girl's zodiac sign, birth flower and birthstone — two fish for Pisces, a violet bloom and an amethyst.

A series of musical notes is carved into the stone above an inscription.

In our hearts, there rings a melody.

One man is an aging cowboy who is divorced and lives alone, who occupies himself with reruns of Who Wants to Be a Millionaire, who talks of living for another 150 years.

The other is a middle-aged man who sells security doors and window-well covers, who is busy with his own vibrant family.

One man believes that Melody went to another world and will return as someone else — maybe even has already.

The other believes Melody is in heaven, and that if he's lucky enough, he will earn his way there one day and be reunited with her.

One is her father. The other is her brother.

A mind of his own

The door to Apartment 302 stands slightly ajar, a grubby old saddle blanket acting as a doorstop. After a knock, a shrill voice answers — "Yeah?"

The door opens.

The man looks like he just climbed down from a horse. His boots and scruffy white corduroy pants are worn and smudged with dirt. His plaid Western shirt has been on him for a couple of days. His battered straw hat has seen plenty of sun and dust.

He is 77 years old. His name is Young G. Freeman. But that's not what he wants to be called anymore. He is now Freeman G. Young, in his own mind, if not legally. He often ignores mail and phone messages left in his old name. Everyone just calls him Freeman.

When he talks, it's not always clear whether he believes the things he's saying or whether he's yanking someone's chain.

He says that women are "murderesses" because they feed their husbands red meat. He's a vegetarian.

He says he wants to master the secrets of a long life, and he figures people in the Himalayas are his best bet.

"Go there for four or five years and get the color of my hair back," he says, "and get rid of the wrinkles."

He grew up in Fruita on Colorado's Western Slope, started "cowboying" — as he calls it — in 1943, and married his wife, Elizabeth, in 1950. By the fall of 1961, they had six children: Joy, April Melody, Smith, Gay, Flint and Starr. They lived on a farm along U.S. 34, a bit more than a mile from the Auburn school.

Happy girl

That morning 45 years ago started out as ordinary as any other in the Freeman household.

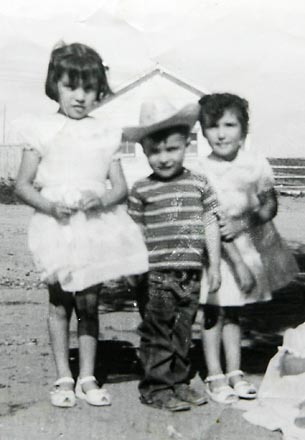

The school bus pulled up outside the small farmhouse. Joy, 10, Melody, 8, and Smith, 7, climbed on and made their way to a seat on the right side.

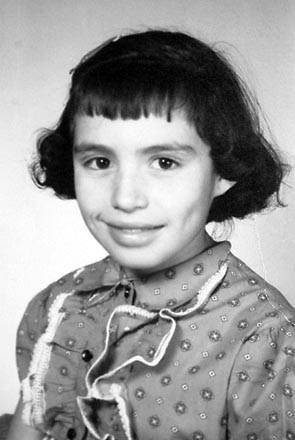

Melody was a happy girl with long, curly black hair and dimples. She didn't so much walk from one place to another as skip. She slid all the way in against the window. Smith — called "Smitty" by his friends — sat in the middle, and Joy was on the aisle.

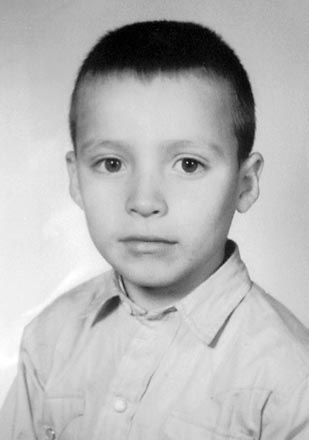

A short time later, in the aftermath of the accident, Smith awoke on the railroad tracks. His first thought was to walk home. Joy found him. She had a nasty gash in her arm. Smith's head was cut open and he had a slight concussion. They walked with two boys to a farmhouse.

Their father was already in Greeley when he heard a sketchy radio report about a collision involving a train and a school bus. He didn't think it was the bus his kids were on, but he headed home anyway.

As he talks about that day, Freeman's raspy voice breaks for a moment. He sits at a cheap folding table in the club room of his Greeley apartment building. His mind is herky-jerky — one minute, he's talking about Colorado's rivers. The next, he's on to some piece of trivia he picked up on Millionaire.

"Do you want to go to the cemetery?" he asks suddenly.

A few minutes later, inside Linn Grove, he walks among the monuments, finds the pink stone.

"She was my favorite girl," he says. "I had a saddle for her and a little horse for her. She was going to be my cowgirl."

That permanently shrill rasp of a voice cracks.

Ghostly sight

Smith Freeman, like his father, decided what people will call him and what they won't. He no longer is called "Smitty" by anyone.

He is 52 years old, a husband, a father of six, including 13-year-old April Dawn. She was named in part for his lost sister, in part because he always loved the name.

He sits in the living room of his century-old home in the foothills west of Berthoud, thinking back to the accident. To the weeks and months after it. To the toys sent by well-wishers — a tractor-trailer rig with a crank-up rear door to let in the plastic animals, a windup car that would break into pieces when it smashed into the wall.

He remembers the night he awakened on the bottom bunk in his bedroom and looked toward the open door. Hovering there was an apparition, about 4 1/2 feet tall, glowing white, with fuzzy edges.

"It's like what you'd see in the movies," he says. "I just thought, 'Well, maybe it's my sister saying 'hi,' or maybe it's not.' But who knows?

"It was scary."

He can recall, too, the day he finally felt the full impact of losing his sister — the one who would roughhouse with him and tell their parents he'd thrown a snowball outside, even when he hadn't.

He thinks he was alone. He may have cried.

"It's like I'm outside and here comes a breeze," he says. "All the feelings just came and finally settled on me."

Thinking of the future

Freeman talks on the trip back from the cemetery.

"I don't like to be around those goddamned guys who only want to reminisce and talk about the past," he says. "To hell with the past. Think of the future."

He is hard of hearing — the result of a near-electrocution when his harvesting combine touched an electrical line. He has a nasty scar on one hand and three toes burned off one foot.

"I don't let that hold me down," he says. "I only got 150 more years to go, so I can handle it."

How did he handle Melody's death?

"When your time's up, when your time's up — you're going to go across," he says.

Where is Melody today?

"She may be in another nation," he says. "She may be in the spirit world. I don't know. If it's for me to know, I'll find out."

The Creator's will

Smith Freeman talks about the lingering effects of the accident, the fallout on his family.

Television images of war, of bodies strewn about, make him feel like throwing up. He and his sister, Joy, have talked only once — maybe a decade ago — about losing Melody, about surviving. Even then, they just nibbled around the edges of their memories. Joy doesn't want to talk about it for the newspaper.

Smith is close to his mother, Elizabeth Freeman, who lives in Fort Collins. But he seldom sees his father. Sometimes, when he talks with his brother, he'll say "your dad," not "our dad."

"We don't agree on very many things," Smith says. "We have completely different belief systems, and I don't think he's going to change."

Smith doesn't believe in reincarnation. He visits Melody's grave every year or two, and he is confident he knows where she is today.

"The good news is, according to the Bible, children go straight to heaven," he says. "With children there is no 'if.' "

He does share a few things with his father. They both hope to see Melody again some day. And they both accept that some things remain a mystery to them.

What happened at the crossing on Dec. 14, 1961, was the work of the Creator, Smith says, and that's not for him to understand — at least not now, he says.

"Clearly God, who created us, thought I should have that experience and live through it," he says.

NEXT: Silence